This is the final installation of a three-part series entitled “Ten Lessons from Flint.”

“There are plenty of different paths for people to take to be good advocates … This is about being willing to stand up and say [that] you don’t think that something is going the way it should.” –Dr. Aron Sousa, Interim Dean, Michigan State University, January 26, 2016

Exposing contaminated and corrosive water in Flint was necessary and life-saving, and the story garnered significant national attention. Yet not every situation calls for advocacy in such a public way. Advocacy for individual patients and patient safety is also crucial. Whether you’re advocating for an individual patient in a hospital or the public on the national stage, becoming an effective advocate requires practice and training. With the right training and understanding of the advocate’s toolkit, we can advocate for positive changes on behalf of individual patients and the public.

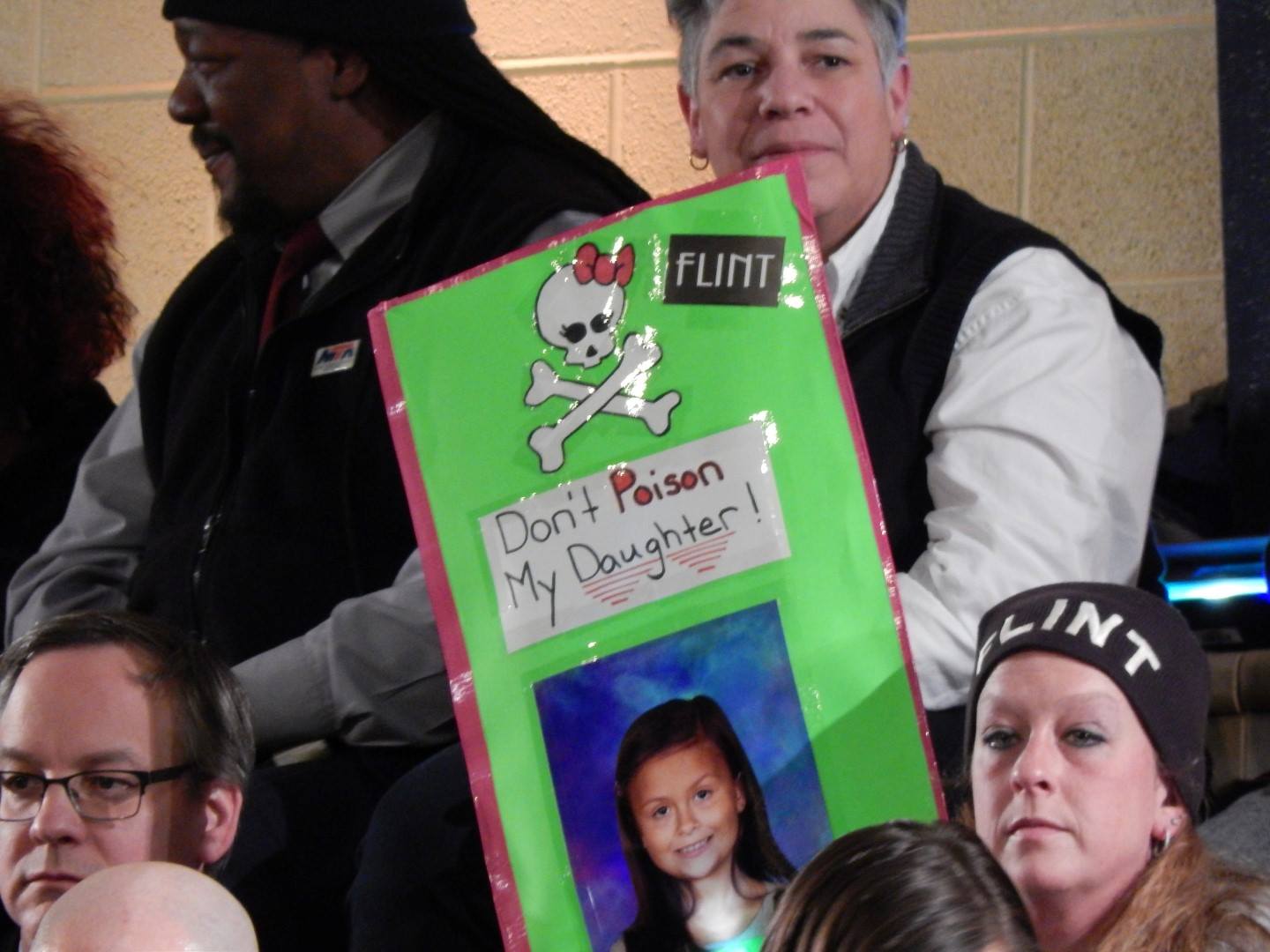

Even well-trained advocates face an uphill battle. The fight continues in Flint. While residents and researchers did get the water source changed and an action plan put in place, the advocacy does not stop there. Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha described the challenge of the fight to come in Flint: “The families are absolutely traumatized — for two reasons — governmental betrayal for two years — they were neglected, forgotten, their voices were not heard; and also for the fear of lead — they don’t know what’s going to happen to their families, to their kids.” Their fears are legitimate, as many exposed children may not test positive for lead now, though their lead levels were elevated when they were consuming Flint River-sourced water. Dr. Hanna-Attisha expressed concern in this area: “The greatest exposure to lead in water are unborn children and babies on formula — and the half-life of lead is very short, so we missed many peoples’ peaks. So babies could have had a peak level at three months or four months or five months, and then when we screened them it was no longer elevated … That’s why we’re treating everybody as if they were exposed.”

Taking cues from professionals in Flint, we can prepare ourselves for individual and public health advocacy in the future.

Lesson seven: “It takes experience, it takes time — but having training is also helpful”

For those who want to include effective patient advocacy as part of their career, these skills can be developed in programs that value advocacy and community-based care. While pediatrics residency programs often include advocacy training as standard practice, all specialties have advocacy training options.

When trying to grow as both a physician and advocate, the values of the training programs to which we apply are important. Dr. Hanna-Attisha, who directs the pediatric residency program at Hurley Children’s Hospital suggested: “I think the first thing that they need to do is train at a place that espouses advocacy. [In our program] we specifically recruit people who want to serve an underserved community — who want to do advocacy work. Go to a place that values this. Some places don’t — you live in the hospital, you breathe in the hospital. There’s not a thought of prevention or advocacy or community work.”

The pediatric and primary care areas frequently have advocacy tracts, but are not the only options for physician advocacy training, explained Dr. Hanna-Attisha: “You could be a critical care doc interested in helmet safety or gun control. It’s applicable to every specialty … You can find a lot of residency programs and medical schools have social medicine tracks … Many adult programs have a community focus and there are other ones that have integrated MPH programs … There are also preventative medicine fellowships where you can do family medicine or internal medicine or whatever, then go on to do an additional fellowship in preventative medicine.”

The advocacy track might not be for everyone, but it is certainly an option for those interested in making advocacy part of their career. For those who just hope for a taste of advocacy training, a number of professional organizations including the American Medical Association and American College of Physicians have trainings and resources available.

Lesson eight: “It’s part of your job description”

Whether you’re advocating for public health issues or standing up for safety concerns within a hospital, advocacy is part of the physician’s job.

In pediatrics this point is particularly important, as Dr. Hanna-Attish described: “It’s part of your job description as a pediatrician to be an advocate. That is what you are supposed to do. So when people tell me ‘Oh my God, you’re a hero, I can’t believe you did this,’ my reply is ‘This is my job. This is what I was trained to do.’ This is what we train residents to do. Children have no voice. They cannot vote, they cannot tell you ‘I need helmets, I need gun control, I need vaccines.’ It is our job to be their voice and even more so in underserved communities. It is bread and butter pediatrics. You know how to treat ear infections, you know how to be an advocate. That’s what you do.”

Dr. Hanna-Attisha may be on the national stage fighting a public health battle, but she was clear that listening to the individual patient is your priority as a medical professional: “Most importantly, listen to your patients. If a mom tells you ‘my baby has a fever’ or something’s not right — believe them. You’re only seeing something as a snapshot in time. Just believe them.”

This kind of individualized advocacy may be the best way for those in training to hone their advocacy skills. Dr. Sousa clarified the medical student’s basic advocacy role: “This is about being willing to stand up and say [that] you don’t think that something is going the way it should — and that could be in an OR when something unsafe is going on — or on the wards when people are being disrespectful of a patient. That is actually the most important place for advocacy by physicians and students and residents — on behalf of individual patients who are in our care.”

Speaking up isn’t easy as a medical student or later in training at either the public or clinical level. However, your rotation site and medical school should have a system set up for reporting concerns. Dr. Sousa explained: “If you are polite and data-based and rational, hopefully your medical school should protect you … Medical schools have a duty to be sure that students who honestly and thoughtfully report something — even if the student is wrong — that the student doesn’t get in trouble for that.”

Reporting concerns to your school is not the only option as Dr. Sousa went on to explain: “Almost every hospital now has a system for reporting safety concerns. Those can be very valuable for students because they are built for other people who are not at the top of the hierarchy … those are important systems for students to know about if they can’t speak up.”

Speaking up on wards is one way to advocate for patients. For students interested in public-level advocacy, there are training opportunities through medical school and residency.

Lesson nine: “Legislators will listen to you as a medical student”

Learning who to voice concerns to is a major part of advocacy. Legislators can be major allies in making change. Legislators are responsible for enforcing rules in federal, state and municipal governments, funding public projects, and enacting policy that impacts us all. Dr. Hanna-Attisha reminds medical students that interaction with legislators is important in advocacy work: “Our legislators have been the brightest spot of the story … They’ll listen to you as a medical student … Don’t be frightened to talk to these people. Voice concerns, go to meetings, get involved in the community. You have a powerful voice — use it.” She stressed the importance of face-to-face contact: “Personal contact is so important. They can see your passion, they can see your competence.”

Lesson ten: “Invest in the tomorrow issues”

There is indeed a long road ahead in Flint, but teams of educators, nutritionists, community health workers, researchers and clinicians in many sectors are thinking ahead. Dr. Hanna-Attisha and others are ready for the problems in the future: “The water will probably get better, we’ll eventually stop using filters soon — but those are today problems. We need to prioritize and invest in the tomorrow issues — because lead is something you really deal with for decades and generations to come. We are actively building infrastructure. We created this Pediatric Public Health Initiative between Michigan State University and Hurley Children’s Hospital to really be a model public health program. We want to flip the story. We’re going to be studying these kids in 20 years. We want to see ‘look what Flint did — they threw all these resources at these kids, all these evidence-based interventions to promote development and they did not become a statistic to lead poisoning.’ And we owe it to these children — they did nothing wrong … We owe it to these kids to intervene — now.”

Continued progress on behalf of patients requires a new generation of public health advocates and resilience among current advocates. So when you see a public health issue impacting your patients — what will you do? Will you turn a blind eye? Or will you speak up?

If nothing else, take away Dr. Hanna-Attisha’s reminder: “This is why you went into medicine. This is what you can do. You are a credible voice in your community. Use your voice — especially in underserved communities to advocate for your patients.”

Be curious, practice responsible science, speak up, keep training to be the best advocate for your patients you can be and lastly, invest in tomorrow.

For further inquiry:

Dr. Hana-Atisha’s research on blood levels in Flint children in the American Journal of Public Health

Flint Water Crisis Timelines:

How Did Lead Get Into Flint River Water? The Chemistry of a Poisoned City

Pediatric Public Health Initiative – A joint venture by Michigan State University and Hurley Children’s Hospital to support the children of Flint

Flint Water Crisis documents released by the Freedom of Information Act

Image credit: flintwaterstudy.org