Check Twitter.

From two blocks away, it was difficult to tell what had happened near the finish line, but the smoke and the movements of the crowd were enough to know that it was time for us to leave. As we hurried home, I sent the above texts, a mere five minutes after the explosions. Concerned, my friend immediately called with the news that not only had I beaten traditional news outlets to the punch, I had even beaten Twitter.

In the days that followed, the ability to update the world on the events happening around the city (in 140 characters or less) has shaped the entire narrative of this surreal week in Boston. As I write this article, the entire metro area is locked down, but vigilant residents continue to report on every minute detail of the massive, ongoing manhunt in small snippets and shared photos. Twitter has been rife with misleading information and less than savory sentiments, but the speed with which it has kept us up-to-date on the rapidly changing situation has made it an indispensable tool in this unusual crisis situation.

As we track their every word and movement throughout these bizarre events, emergency medical workers (from first responders to trauma surgeons) have taken the spotlight as city heroes. The large, fully-equipped medical tent and the abundance of top-tier hospitals gave Boston trauma teams the edge in preventing what could easily have been an even greater loss of life. My own home institution, Boston Medical Center, was able to get all nine operating rooms up and running and fully staffed in less than 40 minutes, an incredible feat considering the equipment and personnel necessary to treat the extensive shrapnel damage many of the victims received from the explosions.

(I could spend hours gushing over the skill and speed of Boston’s medical community, but instead I’ll simply direct you to Atul Gawande’s New Yorker piece that sums up the situation excellently.)

In the immediate aftermath of the explosions, the city’s hospitals became the city’s focus. News teams scattered to determine the extent of the casualties as friends and families began scouring the city’s emergency rooms to find loved ones injured by the blasts. Within an hour, inspirational stories of runners continuing past the finish line to donate blood at Massachusetts General Hospital began circulating around Facebook and message boards. Suddenly inundated with concerned calls and offers to donate blood, city hospitals needed to be able to communicate the situation quickly to the public. So, like the rest of us, they too turned to Twitter.

The total number of victims (as of 3:30 p.m. EST on April 19) sits at three killed and 183 injured. Those who required greater care than the medical tent could provide were sent to six area hospitals:

Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center @BIDMChealth

Boston Children’s Hospital @BostonChildrens

Brigham and Women’s Hospital @BrighamWomens

Massachusetts General Hospital @MassGeneralNews

Boston Medical Center @The_BMC

Tufts Medical Center @TuftsMedicalCtr

On Twitter, each hospital carries between 3,000 and 18,000 followers. Though many of these may be corporate or spam accounts, they still create a very large pool of employees, patrons and concerned parties seeking to remain up-to-date on all hospital activities. So how did each of these institutions communicate news about the disaster to their thousands of followers and what types of information did they prioritize? What follows is an attempt to identify trends in hospital communication via Twitter in the 24 hours following the Boston Marathon bombings.

The numbers game.

Showing restraint that has been uncommon for journalists covering the story and likely focusing attention on more important matters at hand, none of the major hospitals responded to the bombings on social media until several hours after the initial blasts. The first to say anything on the matter was Tufts Medical Center, nearly a full two hours after the incident:

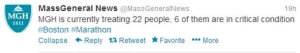

Two things stand out in this initial update: One is the choice to use the established #bostonmarathon hashtag (a method of directing users to all tweets on a specific subject). This increased the chances that any active Twitter users following the incident would notice the announcement. The other is the decision to broadcast only the number of patients taken to the emergency department. While this provides information for those reporting the story and attempting to keep track of the wounded, it does little to help those searching for loved ones or looking for ways to assist the medical recovery efforts. Interestingly enough, another two hours later, Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Medical Center repeated the same type of information in their first social media postings (though BMC chose to relay people to their Facebook page):

Mass General, Boston Medical Center and Tufts Medical Center continued to post updated patient numbers in the days to follow and updates of this type continue to be the most widely circulated tweets originating from these three hospitals. In the scramble to make sense of what was happening around the city, these three hospitals gave the public and the news media what they were looking for: raw data.

Bomb scares and security concerns.

Providing information on the numerical extent of the casualties was not enough to calm the public, though. The fear of additional bombings kept most of Boston on edge late into the night. A cursory search revealed at least seven sites around the city that became the focus of bomb squads pursuing fake tips and suspicious packages, including the JFK Library, transit stations and hotels. Two of these sites were the emergency rooms of Tufts and Mass General:

The decision to quickly address the inaccurate reporting of bomb scares and safety information via Twitter (which occurred repeatedly all over town) should be applauded for several reasons. Most importantly, who better than to debunk information about a hospital crisis than the hospitals themselves? Updates directly from hospital staff via Twitter were not only faster than traditional news outlets, but were also more reliable given that the news media often receive conflicting reports. Quick updating also provided valuable information for those with reason to head for the nearest clinic and takes pressure off of hospital communications staff already overwhelmed by the situation.

Checking in.

Finding the victims who have been scattered across the city is no easy task and reaching out to families and friends is not always possible for hospitals trying to protect patient privacy. An effective and consequence-free strategy for aiding the search was to connect families to support organizations such as the Red Cross and the mayor’s office. Delegating search efforts to organizations with established relationships with city hospitals is an excellent way to speed up the recovery process and reduce confusion in the wake of large-scale disaster.

In addition to caring for the wounded, most of the area hospitals had official teams running in the marathon that needed to be accounted for. My own school, Boston University School of Medicine, attempted to track down runners and fans via the traditional phone tree, a method that can work well but only if you have a clear list of the individuals you are searching for. No doubt, each hospital used their own strategies to track down unaccounted-for individuals, but the extra five seconds it may take to broadcast your search over Twitter (especially when cell phone service was spotty across much of the city) could be the small push needed to reach everyone involved.

How to help.

As previously mentioned, one odd trend to emerge from social media that day was the rapid interest in blood donation as the best means of helping victims. Mass General especially was receiving far more offers of blood donation than they could process and had to begin spreading the message via press conferences and Twitter that those looking to donate should come back in the following weeks. Other hospitals echoed this response in the days following and most made the prudent decision to use social media to redirect donors to the Red Cross.

While the communication of how to help may seem minor in light of more pressing issues like bomb threats and tracking down loved ones, I would argue that for those glued to their computers, these were some of the most important pieces of information to spread. Events like this leave people with a feeling of helplessness and a drive to find any means possible to assist. Giving the public a job to do provides an outlet for the frustration and anxiety that lingers after a traumatic event.

How to move forward.

Each of the hospitals examined here have done a tremendous job when it comes to bringing calm to a chaotic situation. Their communication to the public in the first 24 hours after the disaster played no small role in that. Of course, in the week following the bombings, the messages have changed in purpose, frequency, and tone. Nevertheless, there are some important lessons in crisis communication we should take away from those first few tweets.

The first is that fast communication via social media now dominates coverage of ongoing events and hospitals need to be adept at recognizing their role as well as adapting to changing situations. In disaster situations and the confusion that follows, the ability to inform millions of people of the climate on the ground within a matter of seconds can make a world of difference without expending significant time or resources. The responses highlighted here to bomb scares, security concern and blood donations are excellent examples of quick and clear crisis communication.

Conversely, hospitals that choose not to use social media are putting additional pressure on their communication staff and failing to utilize an effective and simple means of reaching out to the community. Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Beth-Israel Deaconess Medical Center provided very little information via social media during the first 24 hours and while their patient care was certainly exceptional, it may be wise to reconsider how Twitter and Facebook fit in to their crisis management systems.

The role of these services in modern day reporting and disaster management needs to be addressed in the same way that past catastrophes have helped us streamline our emergency rooms. We can’t know when the next disaster may occur but we need to have a plan. And we need to tweet it.