“It’s just a shot away. It’s just a shot away,” blared the music in the operating room.

Music makes the operating room (OR) feel special, magical. There were spurts of blood and a flurry of hands, but I’ll start at the beginning of the story.

I hate to say that there is something exciting about getting called in to the hospital in the middle of the night. Logically, I know that means something bad is happening to someone else, but it makes my heart beat a little faster and my adrenaline surge. I had been following a surgeon at the hospital all Saturday. We didn’t have any cases, so we both went home to rest at 3 p.m.

We agreed that she would call me if anything came in. She always rolled her eyes when I asked her to do this because she thought I should probably just get some sleep and enjoy my weekend. At 8 p.m., I got a text from her saying, “Seems like a quiet night, so unless something changes, let’s meet at 8 a.m tomorrow morning to round.” However, I decided to go to bed early in case something came in that night.

At 1 a.m., I sat straight up in bed; my phone was playing a loud, jangling tone. I didn’t recognize the number, but I picked it up after rubbing some of the crust out of my eyes.

“We have a case. You don’t have to come in, but if you do, come through the emergency department (ED), and I’ll prop the door open so you can get up to the lounge. Be here ASAP if you’re coming. This case needs to go fast.”

I quickly woke out of the fog. Before I even responded, I was pulling on a pair of scrubs. I grabbed two Diet Cokes and a granola bar before half-jogging out the door. It was pouring rain, and there was a chance of the roads flooding that night. I didn’t think about it as I tore down the road, probably a little too fast. My mind kept rifling through the possibilities of the case.

The surgeon hadn’t revealed any details, but I knew that it probably wasn’t an appendix, which is usually not a middle-of-the-night emergency operation. It was definitely not trauma because it was at a small, community hospital that didn’t handle traumas. I thought maybe a gallbladder, but that can usually wait until the morning as well.

I whipped my car into the ED parking lot. I walked into the front door of the ED, past all of the security and staff, and I shimmied through a door into the staff elevator. It always shocked me how much I could get away with in a hospital if I had my white coat on! I slid through the propped-open door on the second floor to get into the perianesthesia care unit and down the hall to the lounge. I took a deep breath before walking inside.

I found the surgeon curled in a chair covered in a blanket fresh from the warmer. She was reviewing the patient’s chart. I handed her the Diet Coke that she didn’t remember she needed. She was scrolling back and forth through a CT scan. She told me to throw my stuff in her locker and look at the CT.

I wadded up my white coat, crammed it into the top of the locker and hurried back. Without turning, she said, “What do you think of this CT?”

My brain was still foggy with sleep, so I wasn’t exactly sure what I was looking at. But it looked like there was an abundance of bright contrast sitting in the peritoneum. which I knew wasn’t good.

The surgeon began to fill me in on the details adding color to the black-and-white CT scan. The patient was a 75-year-old female who had fainted after dinner that afternoon. By that night, a CT scan had been done in the emergency department, and blood was visible in the abdomen. Radiology reported a possible splenic artery aneurysm rupture.

That was when the surgeon had gotten called. It was her turn to try to make this patient better. She looked at me and said, “We are going to get in there, get out and pray that we can patch it up enough for her to make it through the night.”

As if on cue, the intercom that represented the entire operating room screeched to life and said, “We’re ready for you.” The surgery floor always seemed to be so full of life during the day, but at night, it almost seemed haunted. There were empty beds and empty carts, and I could only hear my own breath and sometimes the intermittent hum of a rogue machine.

We walked down the hall towards the OR. I had seen her work her magic before but not on a case like this. Usually bubbly and talkative as we strolled to the OR, the surgeon was quiet that night. She knew that the odds were not in her favor, and she was the last hope this patient had.

We scrubbed in, a process we can never quite speed up that seemed to take even longer with the increasing urgency of the case. The patient was moved into the room seamlessly. The gloves and gowns seemed to appear on the surgeon like a rapid-sequence costume change, and everything seemed to quicken. The surgeon strode over to the table and stepped up onto two step stools.

As I approached to the table, my mind began to wander. I thought that this could be my grandmother. It is easy to lessen the real humanity and emotions once the patients’ faces are covered because then they are just cases: anonymous patients on the table.

Before I got too deep into these thoughts, the surgeon called for a blade. Once it was handed to her, she traced it down the middle of the patient’s abdomen. The suction was shoved into the fresh laceration as she continued slicing. Blood began to seep down the sides of the drape. When we could finally see the abdomen open before us, there was dark, congealed blood pooling throughout. Everything and everyone was at the ready. Hands seemed to just know exactly where to go; nothing was fumbled. There was a steadiness to the surgeon’s voice: urgency without harshness.

The aneurysm in the vessel was hiding within yellow clumps of adipose tissue. Its position did the surgeon no favors, but she was able to clip it eventually. The surgeon began to pack the abdomen with surgical sponges. She was shoving them down into the crevices of the open abdomen to soak up the extra blood.

At the end of the operation, she ended up leaving the sponges within the abdomen. The patient would have the incision closed another day, but for today, she would leave the operating room with a new vacuum-sealed abdomen.

The surgeon asked the anesthesiologist for the values from the arterial blood gas. The anesthesiologist recited them to the surgeon, and I saw the telltale signs of a frown snaking up her face from under the mask. The patient’s vitals were volatile and worrisome, but we had done all we could do for the night. The nurses would keep pushing fluids and blood products after surgery. Hopefully, the patient would remain alive through the night, and the aneurysm clip would remain secure.

The surgeon and I stepped out of the OR and peeled off our blood-covered gowns and gloves. I looked down and realized that blood covered my clogs because, as usual, I had forgotten to put on shoe covers.

It was 3 a.m. We helped transport the patient to the ICU. We stood in silence by her bed listening to the machines pinging and watching the vital signs. Eventually, we agreed to meet back at 7 a.m. to round and check on the patient.

The surgeon decided to crash at the hospital, and I decided to try to make it home on the flooded roads. I was exhausted. I was also worried that the patient would not live to the morning, as she was in a precarious state; I was not sure if we could pull her back from the cliff ledge of mortality.

The rain was hard and pulsing. The roads were thickly covered in water. On the way home, the interstate started to flood, but I kept plodding forward to steal a few hours of sleep before heading back to the hospital the upcoming morning. I came in through my door, kicked off my clogs and fell asleep in my scrubs.

The sleep came quickly, but the alarm seemed to arrive even more quickly. In the morning, the rain had slowed but not stopped as I made my way back to the hospital. I was already tense about seeing the patient. I wandered through to the OR lounge where the surgeon was still staring at the CT from the night before and some new lab results. I could tell from her expression that it was not looking good. She didn’t turn to me when she said, “We’re taking her back to the OR.” She stood and quickly paced down the hall, and I didn’t ask where we were going because I knew that she did not want to be bothered.

Eventually, we ended up in the family room of the ICU. About five family members were standing there clutching coffee and speaking in hushed whispers. They quieted more when we appeared. The surgeon said, “We are happy she made it through the night, but she is going to need another operation this morning to keep her alive. I cannot promise anything. Her chances are not good, but we will do the best we can.”

Somehow, the family members did not look surprised, or maybe they were still in a state of shock from the night before and hadn’t yet absorbed this new information.

We moved out of the room, and the surgeon began to assemble the team. She listed them like a batting order: her surgical partner, hematologist, critical care specialist, anesthesiologist, and first assistant. The patient was connected to numerous tubes, hoses and wires, so it was a difficult time moving her to the OR floor. We crammed into the elevator and hoped that nothing bad would happen on the way there.

Once in the OR, there was a flurry of activity. Things were going to go quickly again that morning. The critical nature was weighing heavily in the room; everyone there knew that it was a hail Mary.

There is nothing quite like surgeons in a critical case. There is nothing wasted in their movements or words. The team worked like a machine. Every member of that team knew what the other would do before it was done. The wound vacuum and staples were removed; the abdomen was opened again. It seemed as though time stood still. It was only 8 a.m.

“The floods is threat’ning my very life today. Gimme gimme shelter, or I’m gonna fade away,” wailed Mick Jagger.

It sounded like someone had turned up the volume. I could see the surgeon clipping vessels and saving this woman on the table as the song seemed to crescendo. I cannot quite describe how magical these moments were. There are sometimes indescribable moments in the OR that don’t seem quite real: a suspended disbelief when miracles seem to appear out of the air. With the general feeling of the room, I thought for a second, “There is no way that she isn’t going to make it off the table.”

The room collectively sighed as the surgeons began to navigate the patient back from the brink. The bleeding was controlled, and everything was working perfectly.

Before I knew it, the case was over. The bubble of magic had burst, and the patient had survived another hour. As we all began to strip off our masks and gowns, someone pointed out that it was an all-female team. I tried to hold back the feeling that this could have been the reason that everything went so well. There were leaders, but it was a group effort rather than a single person who saved this patient’s life.

After the surgery, we continued to make rounds but kept wandering back to this patient’s room to talk to her family and evaluate her current status. By the afternoon, she continued to stabilize. She was not awake or out of danger, but her lab values and vital signs were normalizing. That was my last day on the rotation: I finally went home.

I woke up the following Monday and started the first day of my pediatrics rotation. I kept thinking about that patient, though, and I was worried. “How was she doing?” I wondered, but I was afraid to ask. I was afraid to hear that she had passed. I thought of texting the surgeon, but I did not want to bother her after an arduous weekend.

That night, I heard my phone buzz, but I didn’t think much of it. I finally checked, and it was from the surgeon. My heart dropped into my toes. I was afraid to open it. I knew before reading it what it would most likely say.

It said, “She went into pulseless electrical activity this afternoon, and we never got her back.”

I responded that I was sorry, and I knew that the surgeon had done all that she possibly could. She had given it her all.

She sent back a simple, “Thank you.”

For one of the first times during third year, I felt like the physician had the same feelings about the patient’s death as I did. We were both hurting. I could tell that she was grappling with what she could have done differently. She didn’t blame the other team members. She assumed full responsibility.

Losing a patient hurts more than it should. I had lost other patients during my third year of medical school. I thought by this point that I would be able to distance myself, or maybe that it would hurt less, but it never has. Writing this, it still hurts when I think about her. Maybe that’s a good thing.

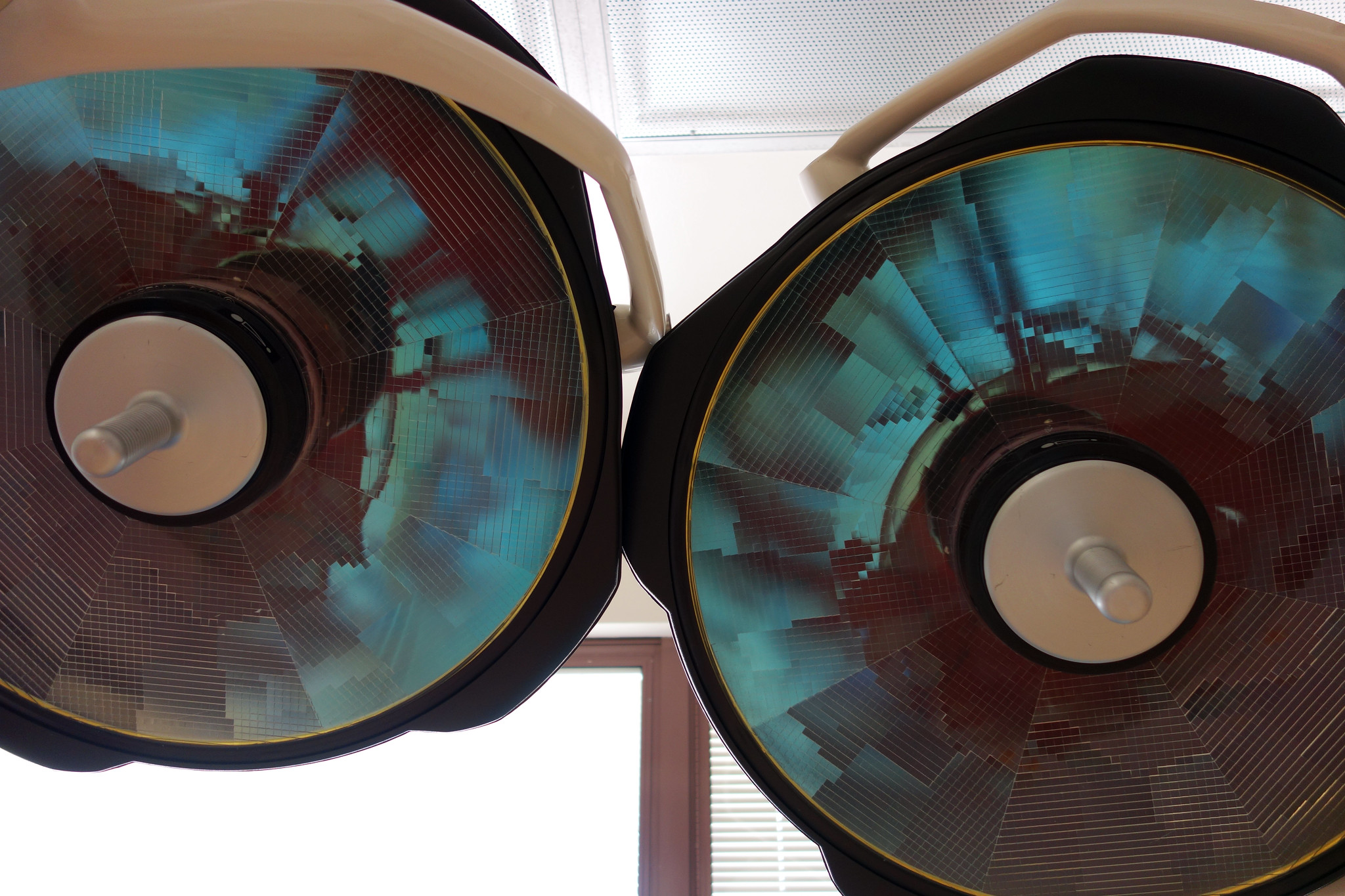

Image Credit: “Operating Room 01906” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Omar Omar