In 2012, Target’s marketing team was attacked: first by an enraged father, then by a storm of reporters and finally by social media. His daughter received a mail advertisement focused on baby-related products. “My daughter got this in the mail!” the father yelled at the local Target customer service attendant as if he was the one responsible. “She’s still in high school, and you’re sending her coupons for baby clothes and cribs? Are you trying to encourage her to get pregnant?!”

However, unbeknownst to him, his daughter was pregnant. But how did Target know? Well, Target’s data analysts simply compared his daughter’s recent purchases to that of other women who were pregnant and had baby registries at Target. The data analysts merged that with demographic data and ultimately, identified 25 products that when purchased in combination could indicate an increased probability that a woman was pregnant. Target could predict with 87% accuracy that a female shopper who had purchased cocoa-butter lotion, a large purse or diaper bag, magnesium supplements and a blue rug in the month of March was pregnant with a boy whose due date was in late August.

In response to the public backlash, Target simply diluted the “expecting a baby” ads with products unrelated to infancy. It found customers were more than happy to use the targeted coupons as long as the ads didn’t hint that the company knew something it wasn’t “supposed to know.”

Since the public perception of privacy has greatly changed, what then seemed odiously invasive would now be deemed nothing short of quaint. People have become more tolerant and open concerning their day-to-day activities and enamored by internet advertisements that are tailored specifically to them. With little to no public scrutiny, health insurers and data brokers have profitably allied to accumulate personal but currently public data about hundreds of millions of Americans. This is personal information pertaining but not limited to social media posts, GPS location, genetic sequencing, and consumer data.

The wearable fitness trackers, the ubiquity of social media, the universal search engines and the “everything store” simply did not exist when Congress enacted the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Thus, the United States has a health privacy infrastructure in crisis with laws, regulations and oaths that protect only one source of information while other more robust and encompassing sources are rapidly developing.

This current legal structure on personal-data regulation in health care analytics was recently addressed by Brandi Collins-Dexter, the media justice director for Color of Change on February 26, 2019 in front of Congress. She testified by saying “Internet service providers and third-party analytics partners can track the times when someone goes online, the sites visited and the physical location … Visits to a doctor’s website or to a prescription refill page could allow the ISP (internet service provider), platform or a data broker partner to infer someone in the household has a specific medical condition.”

Ideology concerning government’s role in this exchange varies widely across nations. On one end of the spectrum, the European Union recently passed the General Data Protection Regulation Act prohibiting the acquisition of personal data without the direct and explicit consent of its utility. It ensures its citizens the right to access their own data as well as protects their “right to be forgotten” which forces the data controller to erase personal data upon users’ requests. On the polar end, the Chinese government has partnered with its major corporations such as Alibaba, often referred to as the “Chinese Amazon,” to generate an all-encompassing data-driven “social credit score,” known as the Sesame Score. In China, this score is constantly updated according to the growing number of analyzable contributing factors including a citizen’s health records, private messages, financial position, gaming duration, smart home statistics, preferred media, shopping history and dating behavior. By the end of 2019, the Sesame Score is intended to standardize the assessment of citizens’ and businesses’ economic and social reputations as well as their access to luxuries including health insurance.

Somewhere in the middle lies the United States. Thus far, policy in the United States trends more towards laissez-faire dissonance. While the government is not spearheading the efforts in mandating an individualized cost-predictive profile of citizens, it is not protecting citizens from corporations that are empowered to do so. The lurking contradiction in U.S. policy is simple: If it is not health data, it should not be allowed to be used in health care analytics, and if it is health data, it should not be acquired and analyzed by non-health care entities. However, to date, there has yet to be a major Supreme Court ruling permitting or prohibiting the utility of health insurance profiling according to personal data usage.

At a recent insurance convention in San Diego, California, LexisNexis, a major data broker and analytics company, claimed to use not twenty-five non-medical personal attributes (such as Target) but rather 442 attributes to predict a person’s medical costs. Notably, this was not just to send trivial ads for baby clothes; yet, this time around, it seems that no one matched the 2012 dismay of the grandfather-to-be or the criticism of the Target customer service attendant. At the same aforementioned hearing attended by Collins-Dexter, Representative Janice Schakowsky (D-IL), chair of the House Consumer Protection and Commerce Subcommittee, addressed past violations: “Modern technology has made the collection, analysis, sharing and sale of data both easy and profitable…Personal information is mined from Americans with little regard for the consequences. In the last week alone, we learned that Facebook exposed individuals’ private health information [that] they thought was protected in closed groups and collected data from third-party app developers on issues as personal as women’s menstrual cycles and cancer treatments. People seeking solace may instead find increased insurance rates as a result of the disclosure of that information.”

But why are companies today in such a position to do this? These companies have earned trust through countless on-time, two-day deliveries. They’ve been there with answers for every embarrassing question, every translation, every conversion of the English system to the metric system. They know their users and finish their sentences. It has been a transition from the suspicion to the appreciation of private algorithms supplementing, characterizing and predicting human behavior.

For comparison, society would be absolutely appalled even by the thought of the National Institute of Health offering to sequence their genome, yet over 30,000 Americans pay to submit their private genetic data to companies like 23andMe and Ancestory.com every day, both of which are almost entirely unregulated. Interestingly, an increasing number of Americans want everyone to know where they are, what they are doing and what they ate for breakfast. It’s not so much an Orwellian dystopia of omnipresent government overwatch as it is a societal trade-off of privacy for convenience and social benefit.

Americans are increasingly researching symptoms and self-diagnosing online before they decide whether or not to see a physician. In fact, 72% of internet users search for health-related information online, and 30% of adults have shared health information on social media. What makes this even more alarming is how data brokers, e-commerce and health care players are transitioning from alliances to becoming one and the same. As major industries like Amazon, Apple and Alphabet branch into the pharmaceuticals, medical device and data industries, the boundaries of “health care” are quickly fading. These all-encompassing corporations have evolved under the current interpretation of anti-trust laws focused on protecting the consumer rather than competition.

In these exchanges, however, the user is not the consumer but rather the product. The major tech giants like Google and Facebook operate primarily by characterizing the users of their free platforms to more effectively generate ad revenue. The lifestyle data collected from free platforms is almost entirely unregulated and cross-leveraged between multiple sectors to most accurately predict users’ next purchase, health care costs, and even opiate relapses.

Image source: Medicare Health Plans

Image source: Medicare Health Plans

The grey area lies in what is considered “health data,” but it is hard to imagine data worth collecting that could not somehow be used to analyze a consumer’s health to some degree. Does buying plus size clothing flag a consumer for weight gain? Diabetes? Cardiovascular disease? Would prolonged screen time or ending a longstanding relationship on Facebook lump a person into a high-risk pool for depression?

The vast majority of medical apps seen on the App Store and Google Play fall in this category and are commonly referred to as non-covered entities (NCEs). Ninety-five percent of the FDA-approved health apps have demonstrated insufficient privacy protections. These apps are most commonly used to monitor and log diet, exercise and medication schedule adherence as well as heart rate, weight, pulse and glucose.

Image source: Feeding America

Image source: Feeding America

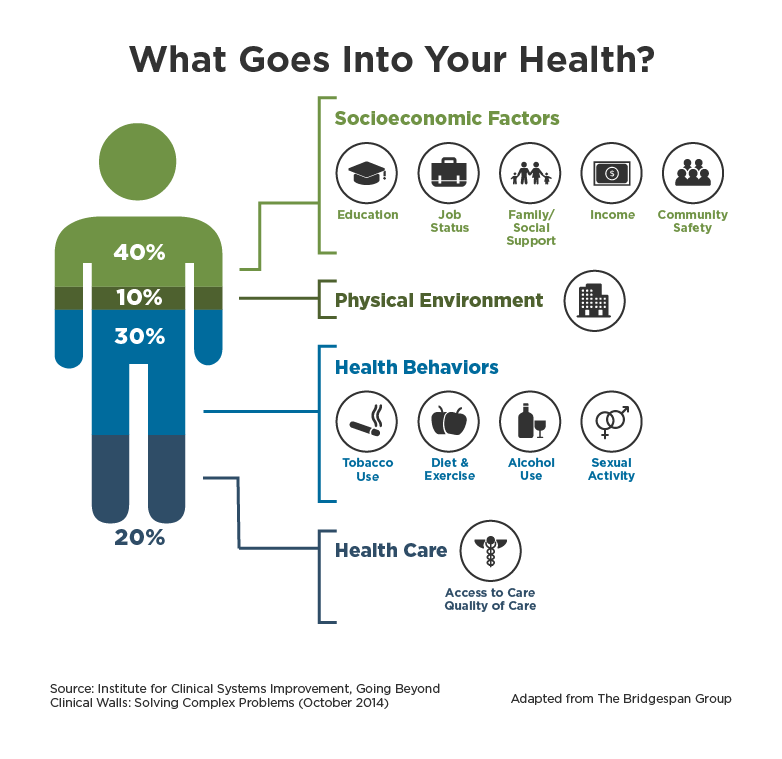

Health care data policy in the United States must be updated to clearly delineate what is and is not considered health data, how health care data can be protected in the digital age as well as set modern ethical standards addressing the use of non-health data in the health insurance sector. While traditional health care analytics have been unidentified to protect the individual, the rise of lifestyle data through the characterization of online profiles empowers a more critical assessment of health care costs. According to a 2015 report from the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, up to half of premature deaths in the United States are due to modifiable behavioral factors: including poor diet, tobacco use, and lack of exercise. Identifying health-predictive lifestyle factors and behaviors can empower society to make more informed decisions, innovate medicine and optimize policy.

In the private sector, identifying lifestyle factors associated with individuals at risk for high treatment costs will only create barriers to care for those who need it most. However, if used in a proactive manner, lifestyle data could greatly enhance the understanding of human behavior by identifying patterns and delineating optimal and maladaptive tendencies. Nevertheless, ignoring the use of such information across sectors (social media, consumer, genetic sequencing, insurance) through undisclosed methods only empowers insurers to capitalize on unfounded statistical correlations, undermining the concept of pooled risk that buffers the cost of care to those who need it.