“If I begin to repeat myself, just tell me. I have Alzheimer’s. At least, I think I do,” the elderly gentleman said with a smile.

This elderly patient of mine was a jovial gentleman and in fantastic shape with unremarkable vitals on physical examination. If it was not for his diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, the physical and emotional state of this patient given his age is nothing less than enviable.

A narrative filled with stories emblematic of living throughout the mid-1900s, he described to me the fading memory of lovers and loved ones while looking at pictures of them in his wallet. The sight of their faces can, at least for now, trigger memories of the past for him: memories of joy and sorrow, of love and lost, of mountaintop and valley experiences.

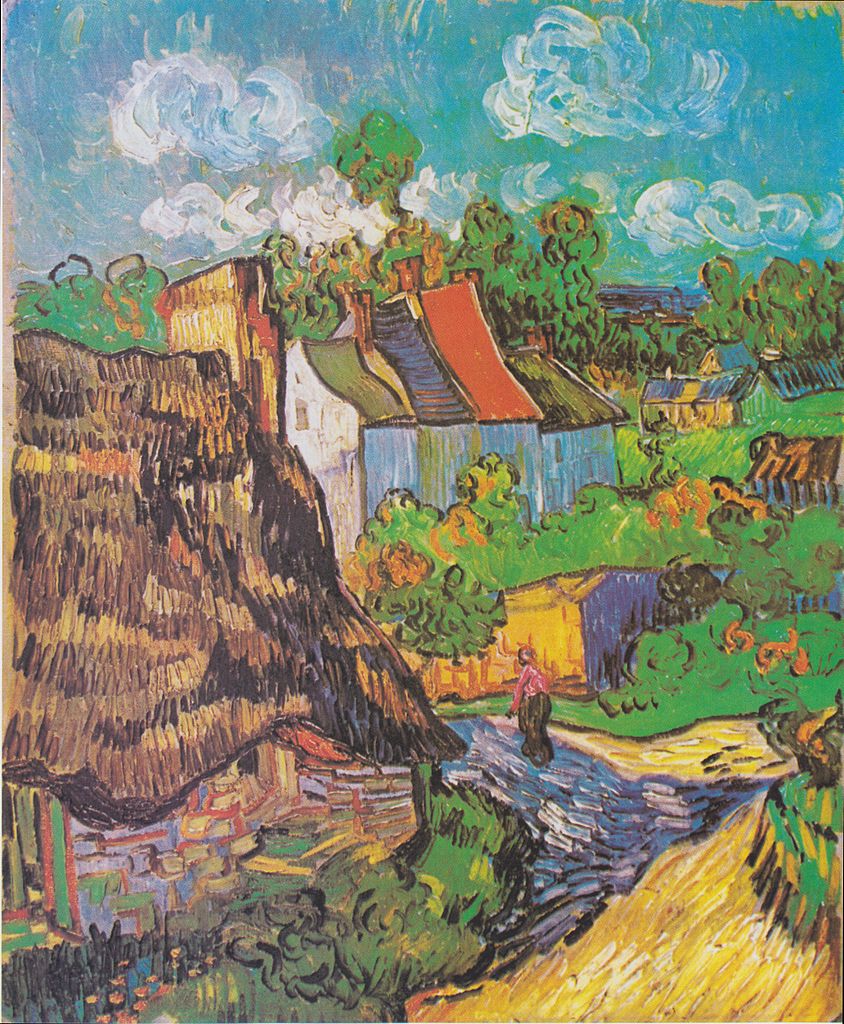

I noticed in the periphery of my vision a painting by Vincent Van Gogh on the exam room wall that I had once seen while on a Valentine’s Day date at the Boston Museum of Fine Art. As I glanced at the painting, I recognized it as Van Gogh’s 1890 “House at Auvres.” After leaving the asylum at Saint-Rémy in France in 1890, Van Gogh made his way to Auvers-sur-Oise, which is north of Paris. Despite Van Gogh’s depression while at Auvres, he managed to produce around 100 pieces of art in 70 days.

As I recalled these memories of a date and the brilliance of the last two months of van Gogh’s life in the context of my patient’s inability to remember so many precious details of his past, I became overwhelmed with the fear of fading memories and experienced what psychiatrist-anthropologist Arthur Kleinman refers to as the “powerful, enervating anxiety created by the limits of our control over our small worlds and even over our innerselves.”

“Are you a gin or vodka guy?” he said in excitement as he seemed to recall an all-but-faded memory from his past.

“Gin. Why?” I asked.

“On that piece of paper, take down the following recipe for my famous martini,” he said on the edge of his seat.

My patient began to describe the intricacies related to the art of mixing drinks in astounding detail. After a few minutes, however, he became forgetful of what he was talking about and I used this opportunity to continue the medical history.

I realized during the disconnected memories of this patient that the powerful, enervating anxiety I was feeling was due to the discomfort that comes with the idea of being faced with one’s mortality. We often think of mortality in terms of physical death but mortality can also be relational and historical death — an inability to recall one’s past, respond to one’s present and to project hope onto one’s future.

The ominous words of Rosencrantz from British playwright Tom Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” concerning the moment one becomes aware of mortality distracted me: “We must be born with an intuition of mortality. Before we know the words for it, before we know that there are words, out we come, bloodied and squalling with the knowledge that for all the compasses in the world, there’s only one direction, and time is its only measure.”

My patient was aware of the direction and measure of his compass, which was the reason why he was wrapping up loose ends in his life while he still could. Van Gogh seemed to be aware of his inability to reconcile his larvate epilepsy with a night sky that was no longer starry. Both my patient and Van Gogh were in touch with difficulties I currently chose to ignore because of the existential difficulty they would pose. As medical students we are taught to demonstrate empathy during the medical history, yet we are not always given the tools on how to handle enervating anxiety that comes with being vicariously introspective.

“Alright, sir, I’ll go talk with Dr. Green about our conversation and we’ll come back and try to address your concerns today.”

“Do you ever take a break?” he laughed while leaning forward to give me a pat on the knee.

“Occasionally,” I smiled back.

“Oh, then let me tell you how to make a good martini!” The excitement was beaming from his face as he seemed to temporarily re-remember one of the joys of these fading memories of love and martinis, not recalling that he had given me the recipe a few minutes earlier.

“I’d love to hear it, sir.”

Author’s note: Names and identities of the individuals in this piece have been changed to ensure anonymity.

Image source: F805: Houses at Auvers at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston licensed under the public domain.