Fareedat Oluyadi:

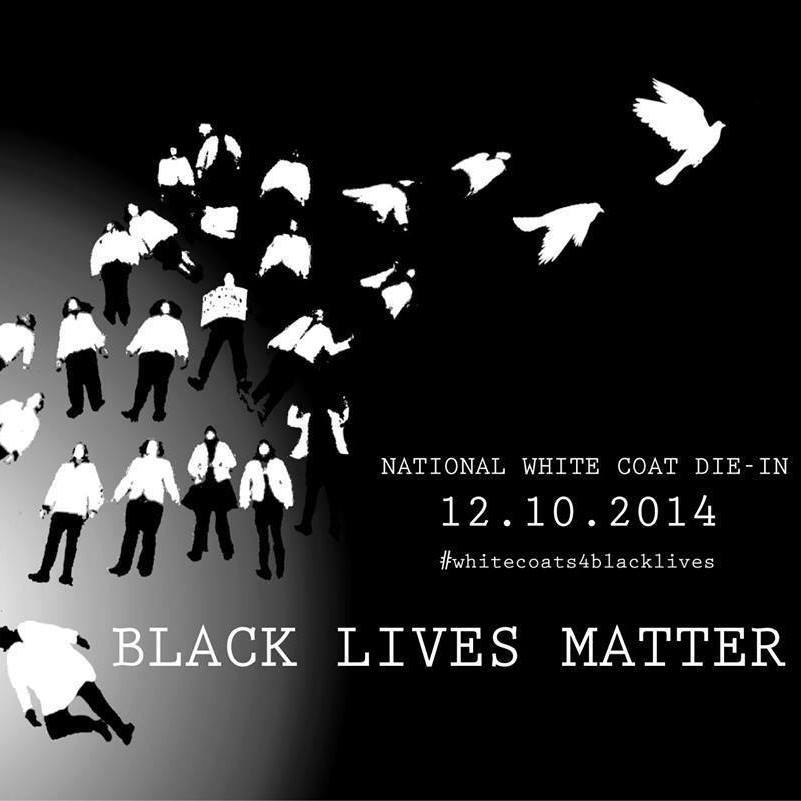

Maybe it was excitement that I was partaking in something greater than myself. Maybe it was guilt that I had not been closely following the nationwide outrage and responses to the Michael Brown and Eric Garner cases. But other than my dreaded neurology shelf exam that Friday, the White Coats for Black Lives Die-In was the most exciting thing on my calendar all week.

I had been shocked when I heard about Eric Garner in July 2014. He died in Staten Island, New York as a result of “compression of neck (choke hold), compression of chest and prone positioning during physical restraint by police” as per the medical examiner for New York City. A grand jury had decided not to indict the police officer in Mr. Garner’s death. Not long after Mr. Garner’s death, the world was shaken to learn about the brutal killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old teenager who was fatally shot by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. There too, a grand jury had decided not to indict the police officer.

I heard about the event from a student organization email. Planned by Physicians for a National Health Program, medical students from across the United States were coming together to participate in a “die-in” to protest racism and police brutality. I saw this as a great opportunity for us to demonstrate that the discrimination occurring on the streets of Ferguson and Staten Island was no different from the discrimination and disparities that affected our most vulnerable patients. I was in!

On the day of the action, my excitement turned into hesitation. As the event approached, I was gripped with apprehension. This was the first time I was engaging in a political protest. Before embarking on my medical training, I always saw myself as separate from the politics around me and I strived to never be poisoned by it. The irony is that over the past several years, I have learned that I am training in one of the most political and racialized institutions: the health care system.

I tried to understand why I was scared. I am a minority student, a black woman, exposing myself in the midst of the majority. I also recognized that not everyone was in support of this demonstration and some of my fellow students were calling for the initiative to be stopped. It was only then I knew, regardless of my insecurities, my presence at the protest was needed. I would be part of the injustice if I had the opportunity to participate but did not.

When I arrived at the site of the action, I was overcome with both fear and pride. Seeing a number of medical professionals, ranging from medical students to higher ranking professionals, from diverse ethnic backgrounds overwhelmed me. I quickly found an empty spot and laid down. I could feel my heart in my chest and my mind was racing. I kept thinking, “This is going down in history,” “What is going to come out of this?” and, “Is this going to be a one-time act?”

A familiar presence interrupted my erratic thoughts. I noticed that Dr. Karani, our Associate Dean for Curricular Affairs, had lain down beside me. A moment later in the silence, she reached out her hand. She gripped my hand and out flowed emotions of understanding, empathy and sincerity. She melted away my ambivalence and instilled in me the power, courage and serenity to truly be present, mind, body and soul. Just as I, a minority medical student was feeling exposed and powerless, someone with her status in medicine and health care was also taking a risk, maybe even more than mine.

While some debated whether faculty involvement diluted our message as students, in my opinion it fortified those seven minutes of silence. It also sent a larger message that the long-standing problems of racial profiling and discrimination are not only the responsibility of physicians-in training but also that of established doctors and leaders in medical education.

The “die-in” was a small step to acknowledge and protest the anchors of racism in America. The unified energy that I was fortified with during the demonstration gives me hope that the action is not, and should not be, a one-time act. The subsequent creation of the White Coats for Black Lives national medical student organization has been a critically important development. The group is committed to eliminating racism as a public health hazard, ending racial discrimination in medical care and creating a physician workforce engaged with the struggle for racial justice. There is truly power and strength in numbers, and I am fortunate to be part of a profession and community that defies the status quo and takes a step, no matter how small, in the right direction.

Dr. Reena Karani:

I first heard about the White Coats for Black Lives Die-In action from a student I bumped into in the hallway on my way home from work. He expressed how helpless he had felt hearing the Michael Brown and Eric Garner decisions and told me about the national event that was being planned for medical students to express their concern about the racial injustices faced by many in our city, our nation and our health care communities.

I walked to the subway that night as I always do, passing by the tall New York City public housing buildings that abut our academic medical center campus. I thought about my patients from these buildings whom I have had the privilege of caring for in my outpatient practice for over 15 years. I remembered the many stories of struggle, injustice and inequality that I had heard over the years from my patients. I had always been amazed at their resilience and fortitude during life’s most challenging and unfair situations. I thought about how the planned action was a way to raise awareness and begin a dialogue about racism, disparities and social justice and I wondered, all the way home, if I could participate.

As a woman of color who had been outraged by the recent events in our country, it was not as simple an answer as I had hoped it would be. As a member of the faculty, how would my supervisors interpret my participation? How might those who did not agree with the approach feel about my participation as a member of the medical school leadership team? How appropriate was a “die-in” in a hospital environment where there were sick and dying patients and their families? Could I even participate in a student-led event? Over the course of the next couple of days, I found myself struggling with these and other questions. On the one hand, our office was working with the security and facilities team to address institutional and regulatory requirements such as fire code, entry and exit paths and patient and visitor safety, and at the same time, we were communicating with the student leaders to offer suggestions to ensure a safe experience for them.

On the day of the action, I remained paralyzed with uncertainty about whether or not to participate. The questions that I had been pondering still loomed in my head and I felt unsettled. That afternoon, when my colleagues and I from the Dean’s office arrived at the designated observation area, the space was filled with students from all classes. The leaders offered some meaningful words of context and then clarified a set of instructions before all the students filed into the atrium. As the students lay down, I took in the scene unfolding before me. My eyes filled with tears as I looked down at the sea of young medical students, lying silently in peaceful protest against discrimination and injustice. I walked over to an open spot on the floor.

As I lay down, my heart was racing. What had I just done? Who saw me do this? Was I going to be asked to stand up and stop participating? I looked around to alleviate my anxiety and recognized Fareedat lying next to me. I reached out my hand and found her warm, comforting and strong hand reach out to meet mine. In that moment, I felt my fears and uncertainties melt away. Her presence beside me and our intertwined grasp gave me confidence and reassurance. I knew I had done the right thing.

Over the next several minutes at the action and following the experience itself, I reflected on the events that brought us there that day and the importance of initiatives like these to raise consciousness and open the doors to dialogue and action. This was only the beginning of the journey, I recognize, but with young doctors like Fareedat alongside, I am more confident than ever that we will see progress in our activism against injustice and racism.