A winter chill can trigger quite the flurry of activity on the floors of an urban safety-net hospital. Patients trail in from the cold with a telling set of problems: their asthma seems to be getting worse; shoveling caused a worrying chest pain; their toes are changing color; they have nowhere else to go. Senior staff begin wandering the wards, desperate to create room for those in need. It becomes a hospital-wide effort to get healthy bodies out the door in order to make way for an influx of the sick. And on one such January morning, the solution for an overflowing and quickly growing roster of the sick and weary was just a single step: hand out taxi vouchers and the beds will empty.

I want you to pause and think critically about how you get to and from work every day. How long does it take? How much walking does it require? What modes of transportation do you use? Is it expensive? Do you know how you would get to work on crutches? In a wheelchair? How about in a snowstorm? Or without a driver’s license?

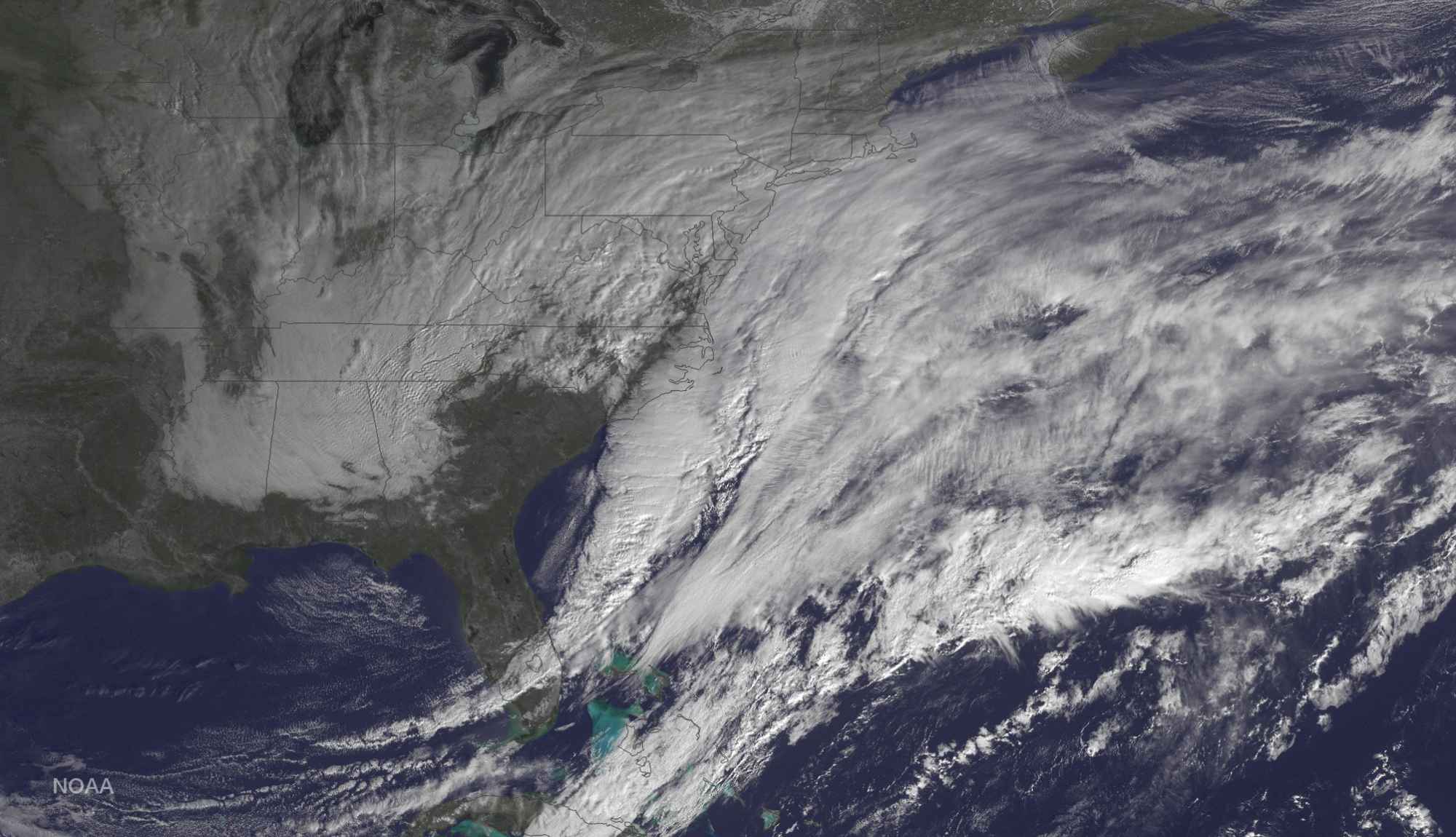

I ask because I have the unheard-of luxury of writing this from home on a dangerously snowy weekday afternoon. That’s because like the majority of healthcare workers in Boston, I rely on public transportation to get to work and any major weather calamity that disrupts public transit massively disrupts the entire city’s health care network. Hospitals cancelled surgeries, closed clinics and provided makeshift sleeping quarters for staff. Local journalist Martha Bebinger on WBUR commented that all but one of the city’s 73 community health centers were forced to close, largely because of the inability to get staff to where they needed to be.

But these are extraordinary circumstances. It’s not every day that Rhode Island needs to clarify their “healthcare worker emergency transportation process” or a Framingham hospital needs to house more than 30 extra staff overnight. And this mess of a travel situation gave me pause to consider the surprisingly complex process patients need to face on a normal day every time they visit their doctor.

That the solution to a precariously overcrowded hospital is to provide taxi vouchers makes a great deal of sense when considering the often-overlooked challenge of physically moving people about a city. What better way to get stable yet frail and tired patients home than to conveniently chauffeur them home? It’s an aspect of care from which most medical staff are often removed. Our patients come to us either by their own accord or by ambulance. We don’t need to guide them to our clinics; they simply appear there. Most of the transportation management that needs to occur happens outside of the exam room. Support staff are usually the ones coordinating ambulance rides, wheelchair-accessible vans, handicap license plates, or parking vouchers. But not every patient will know that these services are available and often the issue of “how do you get to your appointments?” falls through the cracks.

Anecdotally, I have had a patient spend an extra night in the hospital because a wheelchair-friendly ride was not available. I have had patients leave appointments in a rush because the meter was running or miss appointments all together because they could not find a parking spot or the rain kept them from waiting for the bus. We can assess these barriers subjectively as well. We know that transportation is a major hurdle for patients needing procedures like colonoscopies and outpatient surgeries, as well as to follow-up on essential exams such as an abnormal Pap smear. It is critical to account for and address these physical obstacles because even as we hurdle towards the age of telemedicine (while simultaneously reviving the routine of in-home visits) we will still, on occasion, need to get patients to a clinic. It remains an unfortunate reality that physicians can’t stop the rains or become the masters of urban planning needed to fix “the parking situation,” but we can remember to ask our patients some critical questions that apply just as aptly to getting around town as to coping with illness:

Where are you going? And how can I help?

Image source: courtesy of NOAA licensed under the public domain.