Letters of recommendation? Check. Personal statement? Check. Immunization verification? Oh, man. As a third-year medical student, residency is just around the corner. In a year, I will be standing on a podium with my peers in front of hundreds of people awaiting that coveted piece of fabric known as the long white coat. Through the acceptance of this seemingly insignificant outerwear, we will be thrust into an elite club that represents less than fifteen percent of the world’s population. Forget the stethoscope! To the average individual, the white coat is signature of a physician. To the current generation of student doctors, that coveted coat represents a stepping stone, but its true meaning reaches far deeper.

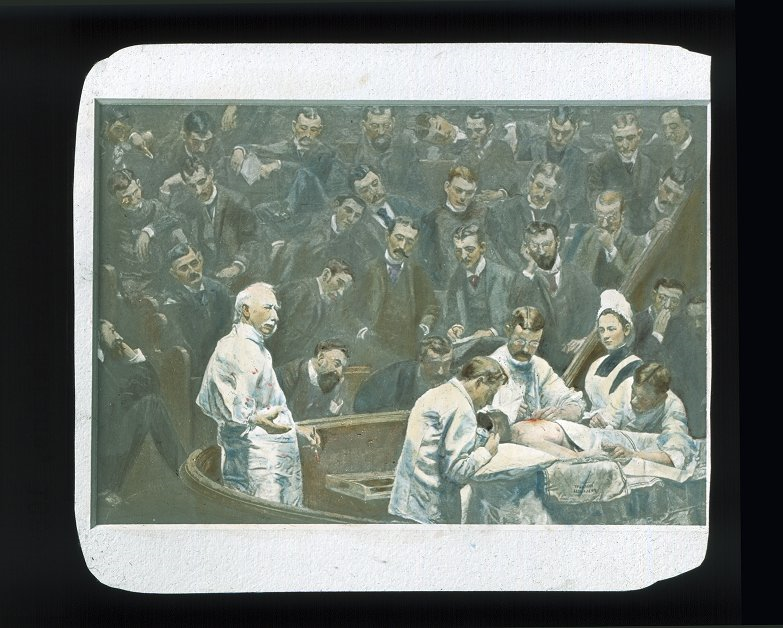

The white coat began as a way to stop the spread of infection during surgery in the late 1800s, but slowly the white coat became associated with the physician. In Western culture, white is often used symbolically in connection with purity and divinity. The use of the white coat inadvertently associated divine powers with a human physician. Not only does that put pressure on physicians to be perfect, which obviously is not possible, but it also puts a strain on the physician-patient relationship. Some studies say that the formal nature of the white coat puts patients at ease because they know that their doctor is competent; however, I disagree. The implication of physician godliness would make me, as a patient, feel intimidated and insignificant. If the physician sees themselves as superhuman, then the void grows even larger. A doctor who feels that they have the power of healing rather than the ability to heal may not be able to empathize with a patient.

Oddly enough, this opinion is likely age-related. An article by Dr. Hochberg in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics states that the older generation is more comfortable with physicians wearing white coats while younger patients prefer that their doctors do not. Our parents and grandparents are more understanding and comfortable with the patriarchal view of the relationship between physician and patient. They realize that their doctors possess skills they do not, and, as the patients, they would feel comfortable deferring to the will of the physician. In contrast, today’s generation are more accepting of doctors diverting from traditional standards. This younger generation is content to visit physicians who have tattoos, drink alcohol and don various piercings. While some may feel differently, others can understand why a younger patient may view the white coat as a barrier of judgment. Unfortunately, in some cases, this may mean that patients may leave out certain key pieces of their histories of present illness for fear of judgment. For example, most psychiatrists do not wear a white coat for this reason. This coat many medical students covet may inadvertently serve as a barrier between them and their patients.

Another meaning associated with the white coat is that of candor and honesty. The word candor is actually derived from the Latin word candidus, which literally means white. The physician is expected to be truthful in all aspects and deliver justice to their patient; however, even honesty can sometimes be misleading.

It is important to consider the human condition and the effect of hope when discussing death and disease. Sickness is always penetrated by a constant hope that the sickness will be vanquished. Often, the physician’s job is not to heal the patient but to keep that hope alive. When getting consent for a surgery, the following sentences are saying the same thing statistically but mean very different things to a patient:

“You have less than a 5% chance of having a stroke during the surgery.”

“You have up to a 5% chance of having a stroke during surgery.”

As a physician, which would you choose? Honesty is the best policy, but it is important to keep it under a veil of rational optimism rather than a shroud of discouragement without portraying false hope.

The ritual of a white coat ceremony at the beginning of medical school started when the Arnold P. Gold Foundation decided that a white coat could be used to signify the transition from student to professional. In 1993, Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons held the first white coat ceremony for its incoming medical students. When I first got to see my name embroidered on that jacket after the first month of medical school, I felt like I was on top of the world. I am a medical student, and, like my fellow counterparts, I have worked tirelessly to get as far as I have. However deep, every medical student has a competitive edge.

Instead of teaching professionalism, the white coat can sometimes breed a sense of entitlement. Professionalism is not something automatic or a virtue that somehow infiltrates our skin after contact with that coveted coat. According to Delese Wear, PhD, professionalism is learned through contact with mentors and professors and through experience. Professionalism can be achieved by extolling the virtues of empathy, altruism and respect while following the accepted standards of medical care. In other words, professionalism can be described as a refined form of humanism.

I am grateful and extremely excited to join the ranks of physicians around the world by receiving my official white coat, but, at the same time, I understand that I will not always achieve the standards that are sometimes associated with its sacredness. I do not think I deserve it just yet. I can only hope that you, my future physician colleagues, and I can understand the greater meaning of the white coat and fulfill its truest potential. That white coat is now our life, and we must not take it for granted.

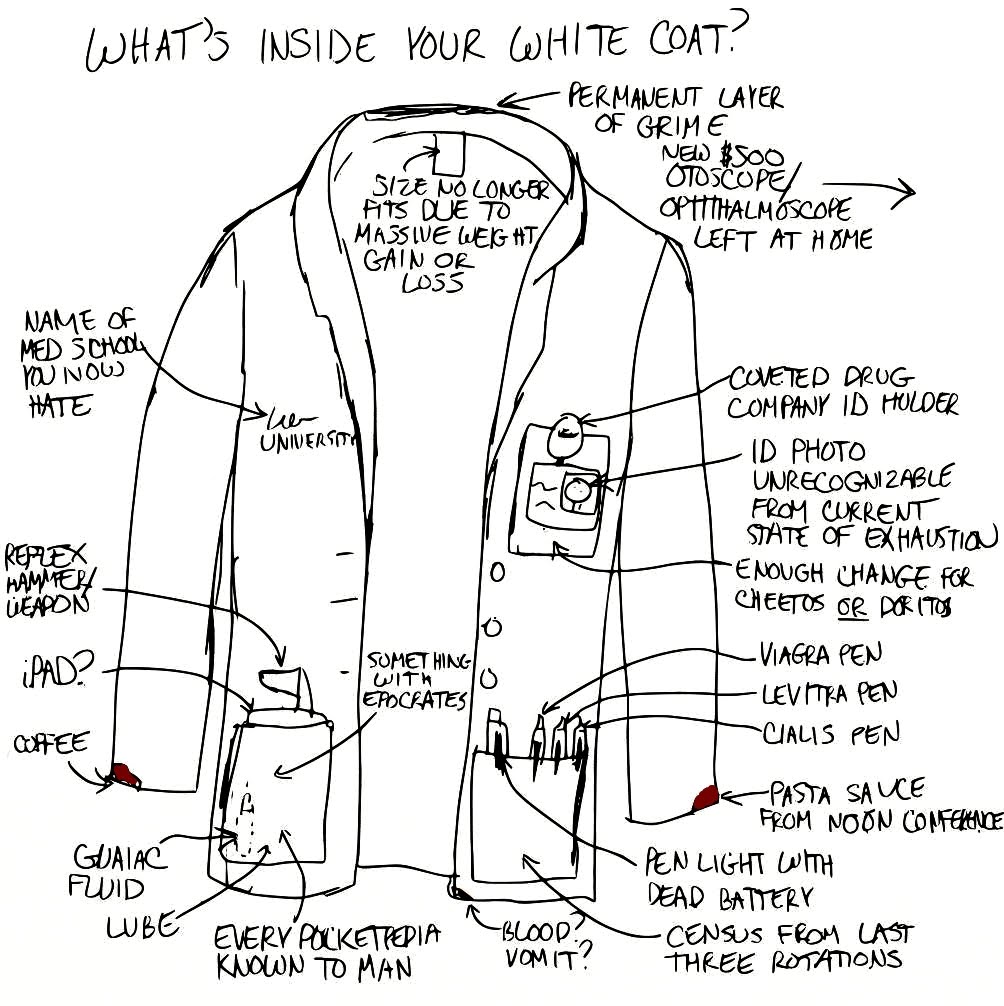

Image credit: “What’s in your short white coat? by Fizzy