I gritted my teeth as I stretched my pinky finger across the fretboard of my acoustic guitar, reaching for the last note in a D-sharp chord. My unconditioned hand was cramping from the fourth chord progression that I was trying to learn, and after straining a little bit more, I huffed in exasperation and slammed my tutorial book closed. After thrusting the guitar into its stand, I flung my arms back onto my bed and lay supine, staring at the textures on my ceiling. I struggled with the thought that I may never become a skilled guitarist, and the vision of downstream achievements — joining a band, traveling the world, becoming famous — began to dematerialize.

My mother purchased my acoustic guitar from a local musical instrument store after I beseeched her, claiming that I needed it for my future. Even at the time, I did not have a clear sense of what my goals really were or why I felt so compelled to learn how to play the guitar. Why not learn something else? Why not learn to play a different instrument? Unfortunately, I did not take the deep dive into my own reasoning and decided instead to act on the notion that it was necessary for some reason.

Needless to say, my efforts to learn to play the guitar were ultimately short-lived. One evening after practicing for about twelve minutes, I sighed dejectedly and returned the guitar to its stand before marching into the living room where my mother was sitting.

“Any luck learning that song?” she asked as she sipped on a glass of soda.

“Nope,” I answered flatly. “I am having a hard time getting past the second verse.”

“Do we need to find a teacher for you?”

“No, I will get it eventually.”

After trying to learn the song a few more times over the next week and a half, I never picked that guitar up and tried to practice seriously again.

—

As children, all of us fantasize about and wish for a romanticized future based on the things we see — but do not fully understand — around us. Many of us wish for things in our lives that are detached from what is most feasible and simultaneously underestimate the effort required to become an astronaut, professional basketball player or something else. While it is important for children to explore these ideas as they develop executive function, this idea of “wishing” or “fantasizing” and setting remote goals does raise an important question: What role does setting attainable goals play in our ability to adapt to changes in our environment and flourish?

By nature, humans are goal oriented. This orientation toward setting and pursuing goals is ingrained in instinctual drives and other motives. Research on the subject of goals has revealed that our ability to have goals is predictive of well-being. One supported explanation for this relationship between goals and well-being is that goal-oriented thinking can reinforce a person’s life meaning and facilitate changing specific behaviors and investing energy in health-beneficial actions. Therefore, there is considerable power for us as future physicians in understanding what influences patients’ patterns of goal setting and overall goal orientation, especially given the challenges in promoting health behavior changes to address the massive burden of chronic disease.

There is one theory that helps to explain why some people might have more difficulty than others in directing their energy toward attaining goals they consider to be important: hope theory. Based in positive psychology, hope theory centers on the assumption that all purposeful human action is goal directed. Charles “Rick” Snyder, a psychologist who worked at the University of Kansas for the vast majority of his career, and fellow researchers developed this theory in the early 1990s. The whole concept of hope is related to positive thinking about a desired goal. As humans, we set goals and then think constantly about what we are working to achieve, and because of this, achieving goals becomes a cognitive process. Hope theory has shown us that hope is a function of cognition, which means that hope is amenable to interventions designed to increase hopeful thinking.

Image created by Ashten Duncan. Adapted from C. Snyder’s hope theory framework.

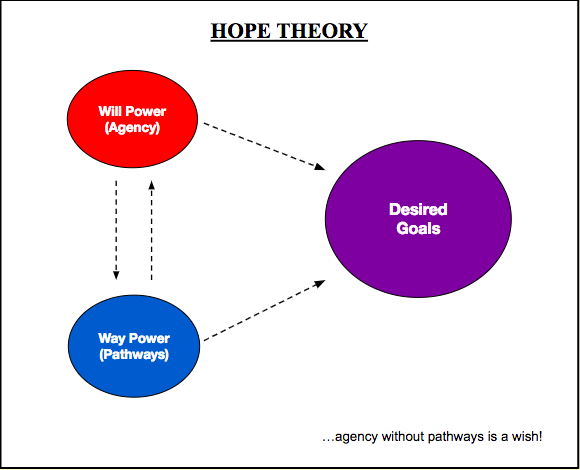

There are two main types of thinking described in hope theory: pathway thinking and agency thinking. These two dimensions refer to external and internal drivers of goal pursuit, respectively. Based on this idea, Snyder described pathways thinking as “waypower” and agency thinking as “willpower” to capture the essence of these cognitive processes. As the “waypower” component of hopeful thinking, pathways thinking consists of identification of resources and other assets needed to make goal attainment possible. Since these resources and assets lie outside of the individual, pathways thinking is considered to be an external driver. As the “willpower” component, agency thinking amounts to an individual’s appraisal of his ability and motivation to pursue a desired goal. Since agency thinking focuses on intra-personal attributes independent of the environment, it is considered to be an internal driver.

For someone to have a high level of hope, both positive pathways thinking and agency thinking are required. If one cannot identify pathways leading to a goal, the result is “wishful” thinking as the image above states. In the context of childhood fantasies, it is not difficult to understand how children engage in predominantly agency-focused thinking without properly identifying available pathways. For adults, a deficiency in either dimension can make something like medical recommendations challenging to follow, which is especially true if the recommendations do not fall within the context of their larger, long-term goals.

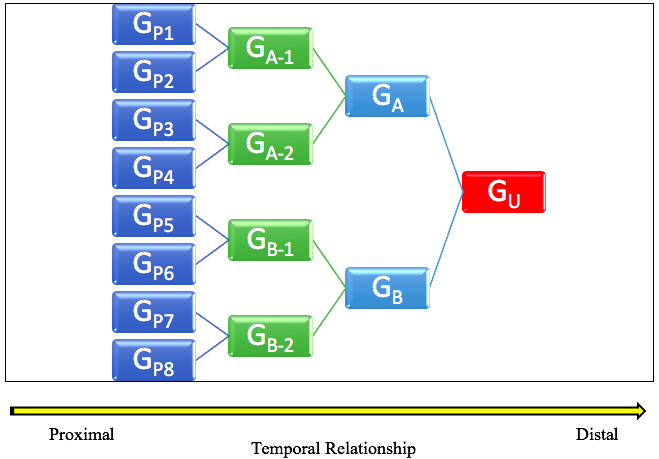

Image created by Ashten Duncan.

The image above presents a generic situation in which a person has a defined “ultimate goal” or purpose (denoted as GU). The larger goals, which feed into this “ultimate goal” (denoted as GA and GB), are fueled by the subgoals shown in green. A step down from these subgoals shows the most proximal goals (denoted as GP1-8). All of these different goals are displayed on a timeline, which distinguishes temporally between more proximal goals and more distal goals. The more proximal a goal is, the more readily controllable it is. Although not always true, proximal goals tend to be smaller goals than distal goals. Also, the smaller a goal is, the less negatively it affects an individual if he is hindered in his pursuit of that goal, especially in the presence of alternative goals (e.g., GP1 and GP2 both leading to GA-1).

What does all of this mean for us as future physicians? Simply put, it means that not all goals are created equally and that people most easily incorporate new goals into their daily lives when they align with their individual purposes and larger goals. As future physicians, we will emphasize the importance of health-related goals that are intended to produce ideal outcomes for our patients. From what we understand about hope theory, we must acknowledge that our patients do the things they do for a reason, even if they are objectively disadvantageous for their health. If our recommendations align with patients’ goals, then they are more likely to be followed.

As I shared at the beginning, I never learned to play the guitar well. In reflecting on this outcome, I realized that I possessed an unclear sense of why I was attempting to become a guitarist. Since my purpose was unclear, so too were the goals contributing to it. As soon as I encountered resistance early in my pursuit, the goal-directed energy I was channeling became unsustainable, and I eventually abandoned the goal of learning to play the guitar. The takeaway from my experience is this: We should never assume that our patients have the same goals as we do for their health. Furthermore, we need to understand that humans are goal-driven beings who need new medical recommendations to align with their specific energy investments in order for them to agree with them and set them as goals.

As medical students, we sometimes lose sight of our purpose for going into medicine and feel that we are exerting ourselves excessively with little feedback from our environment. It is important that we remember that, while we are living through the experiences that come with our training, our future patients are also living through their own experiences. The focus of this column is to examine topics in positive psychology, lifestyle medicine, public health and other areas and reflect on how these topics relate to medical students, physicians and patients alike.