Morning rounds passed without a hitch. I felt the usual: limited understanding and poor clinical synthesis. The residents assured me that this was normal. My team composed of the attending internist, a second-year internal medicine (IM) resident, a first-year radiology resident, and three third-year medical students. Ascending to the workroom, we chatted about life as third-year medical students, patient conditions and the questions we wanted to ask our patients. We exchanged courtesy greetings with the team’s pharmacist, caseworker and social worker.

We began our rounds. The mood was relaxed with a twinge of nervous anticipation as the students knew that oh-too-soon they would present their patients to the attending and then receive responding critique. We headed around the corner and arrived at our first patient. We prepared outside his room and reviewed his laundry list of co-morbidities and non-specific symptoms. He had been in and out of the hospital over the past few months, and now, his wife was present to discuss his options. The patient was under methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) precautions; thus, only the attending and two residents, donning gowns, gloves and masks, entered the room. I and the other medical students eavesdropped from outside the door.

Soon, we were jolted to attention by an overhead announcement, “Attention, code blue. Six South. Attention, code blue. Six South.” No one batted an eye: my team and I were on seven north. “I wonder if we have a patient on Six South,” wondered a fellow third-year student. She glanced down at her pre-round notes and was mildly surprised. “Huh, I guess we do: I have a patient there.” Suddenly, her head cocked to the side, and she squinted. “Well, he could have …” she postulated. Then, the second-year resident walked out of the MRSA patient’s room.

She looked distressed as she quickly de-gowned, de-masked and de-gloved. Immediately, she was on the phone speaking in a concerned manner. The first-year resident and the attending quickly closed the conversation with the current patient and congregated with us. The second-year resident briefed the team as the first-year resident took the mobile workstation to the elevator. The rest of the team headed down the stairs, around the corner and into a crowd of nurses. The second-year resident took command and in a booming voice and announced, “we are the medical team in charge of this patient’s care. What’s going on?”

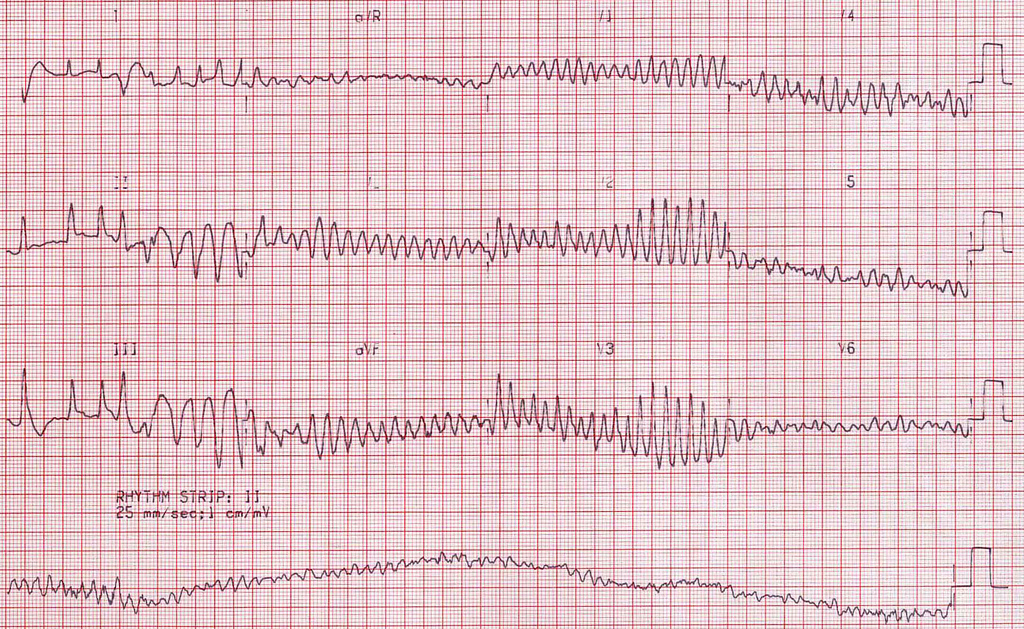

The nurses began to explain in choppy sentences. Apparently, about five minutes prior to our arrival, the patient’s nurse walked in to administer an injection of some kind and saw the patient sprawled across the short side of the bed. He was unresponsive; a code blue was called. Quickly, the triage team attached the electrocardiogram (ECG) leads, and a dangerous yet shockable rhythm flashed upon the ECG screen. Just as the triage team was ready to shock, the patient’s code status was discovered to be ‘do not resuscitate’ (DNR). The team turned off the automated external defibrillator (AED), and the patient expired. When the blood cultures had been returned from the prior day, they resulted in four-out-of-four cultures positive for gram-negative rods.

Our team was in disbelief. The patient was seemingly fine last night and even this morning during my fellow third-year’s pre-round visit. He was a bit hypotensive but without major change from baseline. He was a bit delirious but still oriented to time and place. He had been walking around and talking freely with the nurses the previous night. What could have happened within the last hour and a half for him to completely decompensate? The second-year resident then confirmed the expected sepsis caused by bacteremia and exited the room. I looked at the patient and could only see upright feet hidden under the blanket. It was my first and last image of that patient.

Our medical team collected in the hall while the other team’s resident rushed to print the ECG strip. Understanding the situation, our attending responded appropriately “Alright, anyone want to take a shot at what we could have done?” We were silent. I wasn’t sure if no one knew the answer or if no one wanted to acknowledge it. The attending went on to teach the proper management of bacteremic sepsis. He was also quick to note that specifically, in this case, he believed that no dose of antibiotics following admission would have saved this patient. We agreed in silence.

And with that, we moved on. The second-year resident detached herself from the team to call the patient’s family members and inform them of the patient’s status. Despite its limited utility, she also offered the family the option of an autopsy. I checked my watch and saw that I had to be back on campus in ten minutes. I said pleasantries to our team and left, never to see the team or the patient again.

Image credit: “MS” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Popfossa