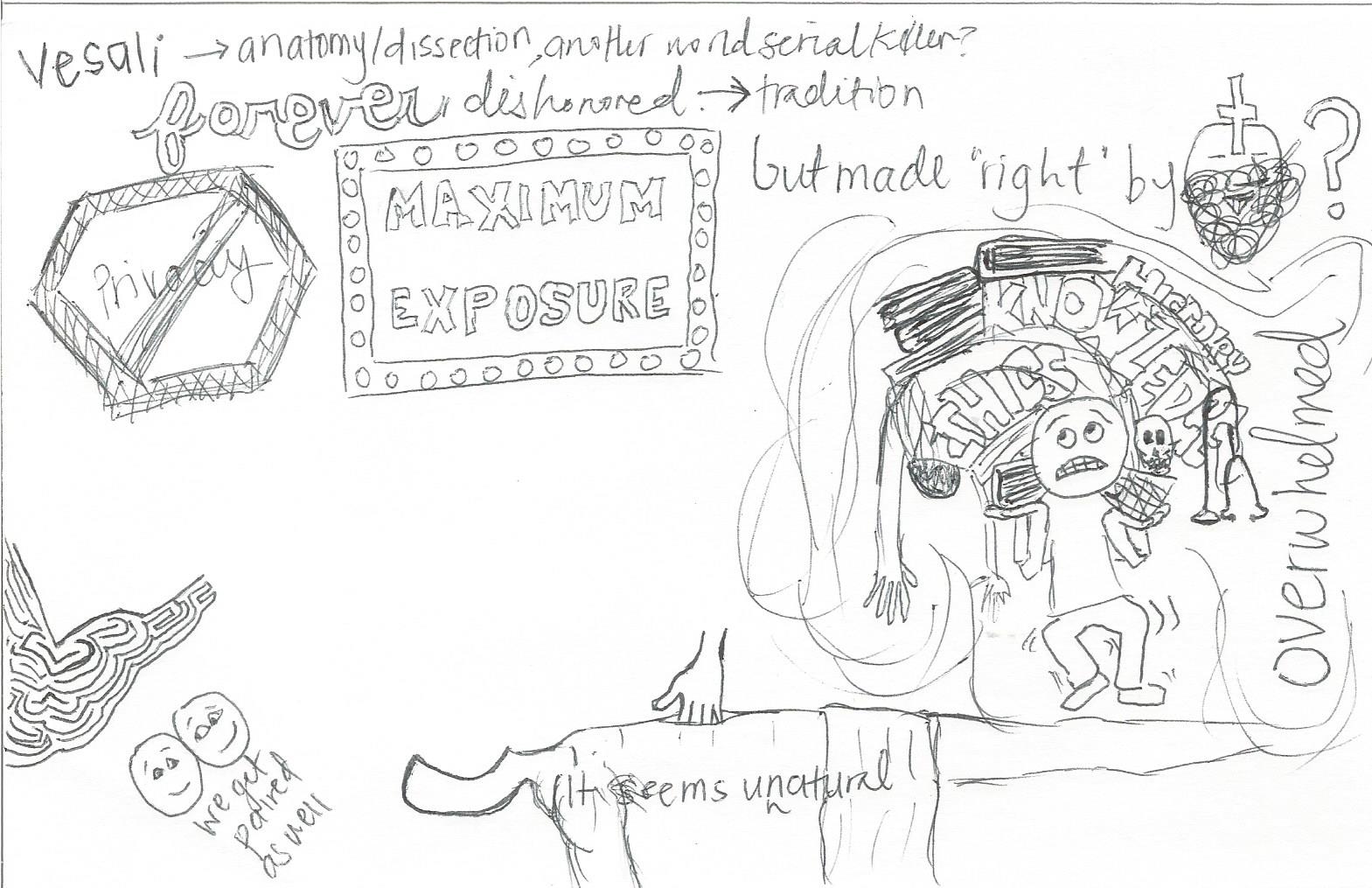

Anatomy as Art: Installation #4

For the majority of medical students, gross anatomy is the first time that we observe and cut into the flesh of preserved cadavers. Whether it is through a longitudinal year-round program or a semester’s worth of concentrated anatomy, most of us develop a unique relationship with the cadaver gifted to us by generous donors.