As medical students across the country enter their fourth year, many will travel thousands of miles to acquire global health experiences from the far reaches of the globe. While much can be learned by exposure to the stark differences among health systems in other countries, there is no doubt that such health disparities also affect the lives of vulnerable populations in our own communities. As a fourth-year medical student, I spent four weeks conducting a community health needs assessment of Burmese refugees in my hometown of Waterloo, Iowa, where I began to learn the meaning of global health at home.

The United Nations defines a refugee as any person who, owing to a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside of his country of nationality, and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”

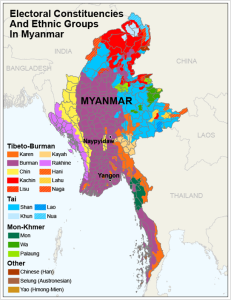

In recent months, Burmese refugees made national headlines highlighting the plight of the Rohingya ethnic minority group. The Burmese refugees in Iowa are members of multiple ethnic minorities that have fled ethnic, religious or political prosecution by the military dictatorship of Burma, which has held power since 1962. These groups have rich linguistic and cultural diversity, with over 135 different ethnic languages spoken in Myanmar. While each ethnic group is different, they have one thing in common: they have all been oppressed by the military junta in Burma.

In the major Iowa resettlement sites of Des Moines and Waterloo, many of these refugees are members of the Kachin, Chin, Karenni, Karen and other ethnic groups who underwent torture, forced labor camps, systematic burning of villages and involuntary relocation to refugee camps.

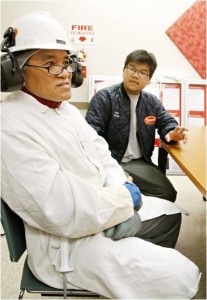

Burmese immigrants began to arrive in Waterloo, Iowa in the summer of 2010, recruited for employment by Tyson Foods. Refugees are authorized to work in the United States by the State Department, and thus are a sought-after source of labor for agricultural industries. Many refugees in Iowa are secondary refugees who have moved to smaller towns to work, often in meatpacking plants or other food processing centers, following primary placement from another location in the United States. There are approximately 1,500 to 2,000 Burmese refugees living in Waterloo, primarily residing in a poorer area of town known as the Church Row neighborhood.

While registered through a global programs elective at my home institution, I worked closely with Cedar Valley Refugee and Newcomer Services (CVRNS). Prior to 2014, the organization was funded by a seed grant of the U.S. Center for Refugees and Immigrants. CVRNS is one of the first contacts for the estimated 10,000 Burmese refugees that have made Iowa their home in the past five years.

For those with a strong interest in global health, mental health struggles are a common theme across populations. Adapting to life in the United States is a huge barrier for these patients. Many newcomers came to the United States from refugee camps in Malaysia and Thailand. Resettlement agencies such as Catholic Charities attempt to place those with family ties to the area. Patients often spent decades in camps with chronic electricity, water and food insecurity. Lives of poverty may impart patients with trauma, mental health difficulties and extreme culture shock on arrival to the United States. However, many patients stay silent for a long time on this very difficult topic. People lived in camps for many years, and lost the ability to hope and plan. Despite previous hardships, this is a population of survivors.

Completing my domestic global health rotation, I was fortunate enough to work alongside local health care service providers and case management organizations. Common barriers to health care in the Burmese refugee population include lack of interpreters, lack of provider knowledge of Burmese culture, low literacy rates and scarcity of basic needs such as housing and transportation. According to the Iowa Center for Health Disparities, these issues will only become more prevalent nationwide with ongoing demographic changes and a rise in microplurality of many distinct ethnic groups.

As stated in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act 1964, federally funded agencies may not discriminate on the basis of language. When applied to health care systems, hospitals and other service agencies are required to provide free-of-charge interpretation. Relying on children or relatives of patients, a common stop-gap measure, should never be part of best practices in a medical setting. The local federally qualified health center (FQHC), People’s Community Health Clinic, now employs three Burmese-speaking interpreters whose hours are adjusted to when most Burmese patients make appointments to accommodate working second shift at Tyson Foods.

The lack of basic health system knowledge and language barriers can cause great distress for the Burmese refugee. Many case managers noted patients’ anxieties over having to gather the courage to call an interpreter and make an appointment. There is anxiety over not knowing the cost of medications, for fear it will bankrupt the family. Even those mundane tasks that the rest of us take for granted can cause great anxiety and stress in these immigrants, especially due to low level of literacy. With every clinic visit, there are reams of paperwork to be completed, and many patients enter the encounter feeling like they are taking a test each time they fill out a form.

Despite the numerous challenges facing the Burmese refugee population in Iowa, one of the greatest strengths is the coordination of community agencies working to provide much needed care. The interdependent network of service agencies is slowly but surely building great capacity for interpretation, casework, health education, cultural exchange and community empowerment. An example is the recent success by the Ethnic Minorities of Burma Action and Resource Committee (EMBARC) to provide backstrap looms to master weavers to nurture and maintain their cultural heritage.

As with any successful global health response in any part of the world, active collaboration of multiple resources is a key asset. The resiliency, strong work ethic and great desire to have a safe life for their children are major strengths of the Burmese refugee community. There is a strong sense of family and community that places high value on consensus, cooperation, humility and duty. Whether or not medical students seek out clerkship opportunities to interact with undocumented migrant workers from Latin America or become involved in urban inner city communities, all of these populations are present in our own communities, and undoubtedly all of them have unmet health care needs. Even in my small corner of the world, all health is global health.

A column reflecting on the privileges and responsibilities we have as physicians-in-training to advocate for those who do not have the power to do so themselves. Devoted to issues of social justice and health equity, this column hopes to spark conversations and inspire action within each reader’s community at large.