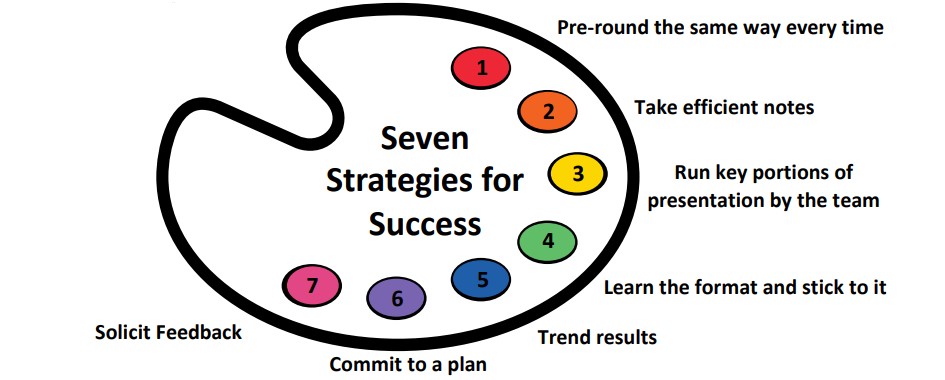

The Art of Mastering Oral Case Presentations: A Third Year Medical Student’s Perspective

The following infographic is the result of my goal to create a resource, backed by literature, from the perspective of a medical student to help other students become fluent in the “language” of oral case presentations at the start of any clerkship rotation.