When I started college, I wondered what subject to pursue. Should I be a writer, an architect, a blacksmith, what should I do? As I struggled to declare a focus of study I thought back to high school on my first day in my art history class. The room lights were dimmed and “Watson and the Shark” was projected onto a screen. The teacher, Mr. Hall, stood at the front of the room, laser pointer in hand, and picked the painting apart. He shared the history, the meaning, the symbolism, the emotion, the color, the form and the brilliance of this painted scene. I was entranced.

Thus, with all my 18-year-old wisdom, I signed up to be an art history major. I loved it. Every day was full of beauty and color. I studied the most influential works from various cultures and across millennia. Every lecture was a thrill, and I was happy.

As time went on my perspective shifted, and I realized two things: One, my dream of becoming a curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art was unlikely to ever happen. Two, I loved learning about the great things people created, but I wanted my life to be more than just the curation of others’ deeds. I wanted to do great things too. I switched my major to psychology and eventually decided to pursue psychiatry.

The Art Historian and the Physician

I often joke about how worthless my art history studies were, but I never mean it. The truth is that my training in the humanities, while being unconventional for medicine, has prepared me to be a better physician and clinician.

Training in the Art of Medicine is not so different from training as an art historian. In art history we study the development of artistic techniques, symbols, cultures, stories, legends, religion, form, anatomy and more. We hone skills to view a picture presented to us and to delve into the brushstrokes and pigment to find meaning. Sometimes we even use X-ray machines. It takes training, it takes expertise, it takes knowledge, it takes work.

Medicine is the same. We are presented with a patient in our clinic, a snapshot of their life. We learn their history. Then using our expertise, our knowledge of certain signs and symptoms, our training in how to approach a diagnosis, we take a simple jumble of information and form a clinical picture to create meaning. It takes training, expertise, knowledge and work.

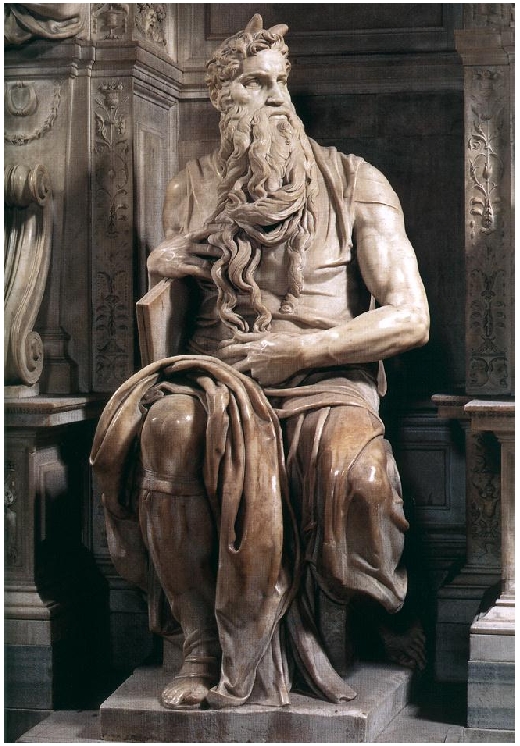

Michelangelo’s Moses: Avoid Being Fooled

Image credit: ideacreamanuelaPps (CC BY 2.0)

In medicine and art, one often needs to understand a conflicting presentation. For example, in medical school, we learn about gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or heartburn. There is a classic presentation we are tested on frequently. A patient has persistent heartburn for years. Suddenly, one day, it goes away. The patient no longer feels any heartburn. Well, this sounds great! What a miracle! It seems to have been resolved. Yet, thinking the problem is gone is a mistake. What has happened is the lining of the esophagus has changed to resemble the stomach’s lining to survive acid repeatedly burning it. This is called Barrett’s Esophagus and the metaplasia, or changing of the tissue, puts the patient at risk for esophageal cancer. Pronouncing a patient whose GERD miraculously healed and sending them on their way is the wrong thing to do. In medicine, we have information that sometimes conflicts with what seems intuitive.

This may have happened with Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses. The sculpture was created to be part of the tomb of Pope Julius II. Unfortunately, Michelangelo was never able to complete the whole tomb. Thankfully, we have many of these amazing sculptures he created for it. Here we have possibly the most revered Old Testament prophet, Moses, who was meant for the tomb of one of the most famous Popes in history. Yet, looking at Moses’ head we see something peculiar … are those … horns?

Yes, yes, they are.

Why did Michelangelo put horns on Moses? Is that a sick joke?

To many of us in modern times, horns are a symbol of the devil. Putting horns on Moses seems like sacrilege. Why then does he have horns? Well, there are two interpretations.

One is that the Bible previously had a mistranslation that described Moses as having horns after his encounter with the Lord and getting the Ten Commandments. Another explanation, which seems more likely, is the symbology of horns. Throughout the history of art, horns have been a symbol of power. What animals have horns? Mostly large, strong creatures like oxen, rhinos or bulls. Thus, the horns on Moses’ head are a symbol of power, and Moses is arguably one of the most powerful people of the Old Testament. This example shows how a simple presentation may look like one thing but have an entirely different meaning altogether.

Starry Night: Finding the Darkness in the Benign

Image credit: wallyg (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Sometimes in medicine, we are presented with a picture that seems worry-free. For instance, when our first child was born, my wife was exhausted. Her breasts ached and were erythematous, she had little energy, and she felt terrible. All the other mothers around her said it was normal and she was simply adjusting to taking care of a baby. Her breasts were just making milk now, she was just getting less sleep, and other platitudes. Eventually, she went to the doctor who almost instantly recognized severe mastitis and got my wife the care she desperately needed.

Thankfully, our knowledge and training can help us to root out disease hiding beneath the benign. The same can happen when interpreting art. A perfect example of this is the famous “Starry Night” by Vincent Van Gogh. To the untrained eye, it is a beautiful tribute to the night sky through the eyes of a madman. However, to one who understands symbols and history, it is apparent to see that it is a testament to Van Gogh’s life as a failure.

Van Gogh, for all his current fame, was a monumental disappointment while he was alive. Even though his brother was an art dealer, Vincent only sold two paintings in his lifetime. He failed at every single endeavor he attempted, except for his suicide.

This painting is the view from his sanitarium window in the Saint Paul Asylum where he was admitted for mental illness one short year before his death. Van Gogh took liberties with the view. For example, he did not paint in the bars of his window. Another artistic liberty is the church in the middle. Its sharp steeple is reminiscent of Holland churches in Van Gogh’s homeland, not of the churches of Southern France where he was committed.

Why a Dutch church? Well, it is a reference to earlier in Vincent’s life. He tried to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a minister. As with all things, he failed and quit. This church is a testament to that failure.

What of the beautiful curving cypress trees reaching heavenward which dominate the left portion of the painting? Well, cypress trees are a common symbol of death. With this knowledge, the painting takes on a new meaning. A hulking sinister shadow of death looms over the scene. It is obviously prominent in the mind of this madman, committed to an asylum for self-mutilation, as he ponders his life’s failures.

Even though “Starry Night” is arguably Van Gogh’s most recognizable work, he saw it as an absolute failure. He hated the painting and felt that he betrayed his artistic integrity to fit in with contemporary impressionistic styles. The painting itself was a symbol to Van Gogh of his failure as an artist. To another painter Van Gogh wrote, “And yet, once again I allowed myself to be led astray into reaching for stars that are too big — another failure — and I have had my fill of that.”

With proper training in art history, one can correctly interpret this tragic painting despite its benign presentation. This is what a physician does. With a few symptoms and a little history, clinicians take a jumble of information, which may seem benign, and find a sickness hiding beneath it all.

Arnolfini Portrait: Don’t Overlook the Details

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

I am sure many medical trainees have felt the embarrassment of forgetting a key detail when presenting a patient to their attending. One of my clinical preceptors told me, “The devil is in the details, but the diagnosis is also in the details.” In clinical cases, it is often the small details that distinguish different diseases. A test question may have very generic symptoms of encephalopathy but once you read a small detail about the patient owning a cat, most students will instantly jump to Toxoplasmosis. Often, the tiny details in a patient presentation or a work of art can tell us volumes. Both the physician and the art historian must pay attention to every detail.

Look at this painting. What do you see?

Do you see a weird plain portrait of a bland anemic couple? That is what I saw when I first was shown this painting. Oddly enough, this nondescript work of art is thought of as one of the greatest paintings of all time. Its painting techniques are the work of genius and it is littered with symbols and meaning.

This is a marriage portrait. The dog at the bottom represents fidelity and loyalty to each other. The discarded wooden shoes, removed from the man’s feet as Moses removed his sandals before the sacred burning bush, represent the sacred nature of the marriage. The curved mirror in the background shows two witnesses of the marriage and the frame around it has depictions of Christ, symbolizing the couple’s faith as a central pillar of their relationship, binding and encircling them.

The way the woman holds her dress bundled in front of her belly symbolizes the hope of pregnancy and children. The green of her dress is a symbol of the couple’s wealth, as green dye was expensive in the 1400s. The white of her headdress symbolizes purity, the red of the bed is passion. The black of the man’s robes symbolizes somberness as he performs his duties to support his wife, as his hand both possesses and supports her own.

Someone equipped with proper training and knowledge can find meaning in the nondescript. Just as an art historian sees layers of meaning in a boring painting, so too does a physician see measles in a rash or endocarditis in a bruised fingernail.

The devil and the diagnosis are found in the details.

Integration of Humanities and Medicine

Art and Medicine have always been close. As medical professionals, it is a mistake to ignore the humanities, for our daily work is with humans. I am grateful for my “useless” knowledge of art history because I genuinely believe that it has helped me hone skills that I use daily in the clinic. Artwork and patients are not all that different. When approaching both, I am presented with a picture. Then I must seek the symbols and background of that picture to form meaning. My passion for art history has made me a better medical professional.

Featured image credit: Watson and the Shark (CC BY-NC 2.0) by mookiefl