Editor’s note: In part one of this two-part series, we explore the state of direct-to-consumer, wearable ECG technology. In part two, the author presents a product comparison and research validating the devices.

Since the Apple Watch released its ECG features in December of 2018, a few users have already exclaimed that the device has saved their lives. Personalized, at-home medical information is in high demand from fitness trackers or genetic tests. Cardiologists Dr. David Sherman, MD, Dr. Gregary Marhefka, MD, Dr. Peter Kowey, MD, and other researchers in the field were interviewed regarding the utility of wearable, in-pocket, direct-to-consumer ECGs and the correct method to identify people who may benefit from these products.

“These [direct-to-consumer ECGs] might be an idea for people with arrhythmias that you don’t catch happening that moment in the office,” says Dr. Sherman, a cardiologist and associate professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center, who has several patients with their own ECGs. Dr. Sherman completed medical school and residency at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, with a fellowship at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. The purpose of the devices is to provide an ambulatory measure of rhythm disturbances that is less costly and cumbersome than alternatives.

While Apple recently popularized the health technology industry in the electrocardiogram (ECG, or formerly known as EKG) market to detect abnormal heart rhythms, AliveCor has sold Kardia ECG products to the public since 2014. These devices deliver alerts intended to identify possible arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF). Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common arrhythmias and is a risk factor for several health problems including syncope, cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) and transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

Nearly 10% of Americans over the age of 65 have AF, and this condition is seen in up to 20% of stroke patients. Despite the potential convenience, direct-to-consumer ECGs are not cleared to diagnose AF in isolation. Instead, they serve as a marker suggesting further workup. The potential influx of data which may include many false positives is a management challenge for technology companies and healthcare providers alike.

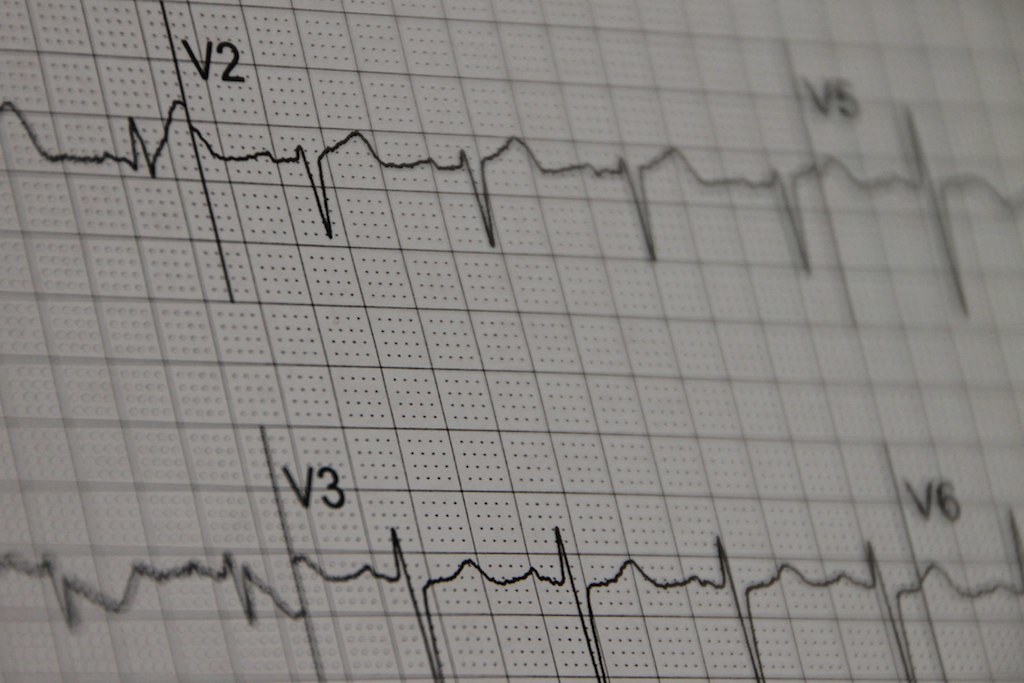

How these are different from standard ECGs

A standard electrocardiogram (ECG) has twelve leads; therefore, it simultaneously reads cardiac electrical activity in twelve directions to portray a three-dimensional impression of the electrical flow in the heart. A pocket-sized ECG reads only one direction at a time generally with leads placed on both index fingers or a wrist and a finger. Apple released two different ECG features in December 2018: a new algorithm for the pulse reader that has been a staple of Apple’s watches since the Series 1 was released in 2016, and a finger sensor built into the crown of the Series 4 watch.

In addition to detecting heart rate, now the pulse reader can detect irregular rhythm, but without an exact tracing. The finger sensor ECG feature of the watch can capture a simple tracing of rate and rhythm that can be shown to a physician to possibly diagnose symptomatic episodes. Apple is also currently comparing the sensitivity and accuracy of the two features.

In contrast with the Apple Watch which is worn, the KardiaMobile uses a small electrode pad which avoids potential interference from hair and technically allows for placement of additional electrodes to analyze additional leads. However, its use for additional leads is neither convenient or immediate compared to a standard ECG. Patients then send the data to their physicians to help determine whether the patients require medication, intervention or a standard ECG.

“Its utility is when using simply your two hands to give a very nice rhythm strip to help diagnose some arrhythmias,” says Dr. Marhefka, a cardiologist at Jefferson University Hospital. Dr. Marhefka completed medical school and his fellowship at Thomas Jefferson, with his residency at training at the National Naval Medical Center. Marhefka’s peers at Jefferson have followed over 250 patients since 2017 with direct-to-consumer ECGs and have two research projects in development.

According to Sherman, these devices present high utility “for people with arrhythmias that you don’t catch happening that moment in the office.”

Wearable ECG devices typically connect to a mobile device application, and users send these readings to a physician. While this is convenient for the public, physicians historically have used more formal, bulkier devices with multiple leads to assess arrhythmias in the ambulatory setting. One of those is a Holter monitor.

Patients wear the wires on their chest, with the recording device in their pocket continuously for a period of time. The data is then sent to a cardiologist for interpretation. Other similar devices send live info to the device company to immediately alert someone of an emergency.

“One lead is enough for some arrhythmias,” Sherman says. “You just want to get an idea. That can lead to further study [of the patient].”

“It’s not just A-fib, even though that’s the focus [right now],” says Dr. Peter Kowey, MD who is a member of the scientific steering committee of a study evaluating the Apple Watch’s optical sensor and is the chairman emeritus of cardiology at Lankenau Heart Institute. Kowey attended medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, a fellowship in cardiology at Harvard’s School of Public Health and the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, and a fellowship in research at Harvard and the West Roxbury VA Hospital.

Because they only get a simplistic output for cardiac activity, single-lead ECGs are not sufficient for arrhythmia diagnosis. “The software has gotten better, but sometimes it suggests something that’s A-fib [atrial fibrillation] when its not, so it has to be interpreted by a doctor because I can tell what’s just an artifact. I’m not going to tell them to use a Kardia if I have something better,” Sherman says.

At-home ECG devices designed to work with a smartphone app may provide unique applicability to patients requiring monitoring for longer durations of time. “If you needed more than once a week or three months [of continuous data] then a Holter wouldn’t be helpful,” Sherman says. Currently for dangerous arrhythmias a chip can be injected under the skin and remain indefinitely. “But people don’t like the thought of having things underneath their skin,” he says.

Compared to the direct-to-consumer ECGs that are $99 to $400, Holter monitors cost between $400 to $1,000, and the chips are even more. “But all insurances pay for them unless there’s a deductible,” Sherman says.

What they can actually tell users

Because direct-to-consumer ECGs have only one lead, they have limitations. They have been FDA cleared to provide alerts for potential AF but are not intended for diagnostic use. Detection of potential AF is possible with these single lead devices for two reasons: it is an arrhythmia limited to one location, and its irregularly irregular pulse variation can be detected without an ECG correlation. The pulse-reading optical sensor on the Apple Watch Series 1-4 can detect this irregularly irregular rhythm as well.

Who they might help

At-home ECGs would be particularly helpful for someone with subjective, intermittent symptoms. Having a basic ECG readily available for symptomatic episodes could provide useful data when considering a diagnosis.

“The AF wouldn’t even have to be chronic [or daily to cause symptoms],” Dr. Sherman says. “The [AF] events could happen once every six months. If people have episodic symptoms outside of the office, if they have heart palpitations or they pass out, then you don’t know what [the cause] is exactly. You don’t know if it represents a benign arrhythmia, or if it’s even a regular heartbeat [with unrelated syncope],” Sherman says. “I have told people to go to an ER or my office the second they feel anything.”

AF is typically not an emergency as an isolated problem but is associated with significant morbidity over time. The classic association is an increased risk for stroke. Diagnosing AF is important for prevention of those complications. “Then, you can get [patients] on medicine in order to prevent the A-fib and stroke,” Sherman explains.

How current direct-to-consumer ECGs could do harm

Though having an ECG at all times might seem helpful to catch asymptomatic individuals who possess underlying anomalies, general screening for AF isn’t recommended. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an evidence-based medicine task force, decided that there is insufficient evidence to currently recommend screening everyone for AF. The overall harms of false diagnoses with further tests or unnecessary treatments might outweigh the benefits. A group of physicians recently disagreed with the task force’s evaluation in a Comment & Response in The Journal of the American Medical Association, citing that merely minimal invasive tests and procedures resulted from screening in two trials. However, a second group supported the USPSTF in reply, countering that other studies still found increased testing overall and that general practitioners misinterpret and misdiagnose ECGs up to 10% of the time. Though at least one study evaluated by the USPSTF detected more confirmed AF via screening than without, another study found that subsequent outcomes, like stroke, were not improved. The task force’s rating is inconclusive, indicating that there is insufficient evidence to support general AF screening.

This rating suggests that the current utility of direct-to-consumer ECGs is limited to the evaluation of infrequent symptoms experienced at home, with less benefit for a young, healthy person who has no symptoms. It’s possible that a wearable ECG could catch an asymptomatic AF in an otherwise healthy person, but the low prevalence of true pathology would minimize the predictive abilities of an abnormal finding. Despite the limitations, continuous wearables like the KardiaBand or the Apple watch have the capability of detecting asymptomatic findings. Because KardiaMobile is not a wearable device, it is not helpful “for things like recurrent syncope, near fainting, or silent arrhythmias, activation devices are not helpful,” says Sherman.

The asymptomatic man who says his device saved his life had it buzz multiple times. But what if it buzzes just once? How long should someone wait? Is this person now getting the million-dollar workup? After all, young people tend to have a completely benign arrhythmia separate from AF, called sinus arrhythmia, where the heart changes pace with respiration. That is why the FDA only cleared the Apple watch for people 22 and older.

Additionally, portable ECGs may not reach those who need it most. AF is a greater concern in people over 65 who may not purchase this technology as readily as those born in a younger generation. In that case, a user might be less likely to truly need it and more likely to receive a false positive diagnosis of AF.

Dr. Kowey has concerns about the burden that physicians will inevitably encounter if direct-to-consumer ECGs saturate the market. “Casual monitoring without a doctor’s prescription brings in a lot of questions. What is the burden to the health care system of all these people [worrying] about their heart? All this data has to be filtered so doctors aren’t deluged with info they can’t handle.”

Those appointments may be occupying time better served for more serious problems. Additionally, people may ignore crucial symptoms as long as the personal ECG says they are okay. “Information processing is as important as technology refinement,” he says.

How they affect privacy

With the ECG data transferred, these companies become third-parties in physician-patient communication. As such, these firms are obligated to comply with privacy laws about protected health information. AliveCor’s website states, “Yes, AliveCor is HIPAA compliant … as well as [compliant with] HITECH regulations.”

Similarly, Apple’s data gathered on the health app can only be shared via the export function. Interestingly, Apple’s health app also has spaces to enter general health records to track for personal use.

Although it is HIPAA compliant, that doesn’t mean AliveCor won’t use the data. Its frequently asked questions declare that the organization doesn’t resell data; rather, it uses de-identified information for feature improvements. In reality, this indicates that it shares the information its investor Omron.

Reaching beyond atrial fibrillation

Researchers hope that the next lines of products will distinguish more than just AF. AliveCor has at least four ongoing projects: a new six-lead ECG, detection of long QT intervals, detection of arrhythmias from hyperkalemia and research on myocardial infarction. The first three are at different stages of clinical trials in order to receive FDA clearance. The fourth is a six-lead ECG, called the 6L and previously called Project Triangle, that opened for pre-order in the spring of 2019.

Though lofty goals for these bigger features exist, the reality is that the current products marketed to warn for AF are brand new themselves. “I’d have to see people use it more and see the data it makes electronically,” Sherman remarks. “If it looks like I can make diagnoses off that, then it’d be useful. But it’s hard to recommend just for that now. Even the Kardia I’d only recommend if I know they’re willing to spend the money.”

For portable ECGs like watches, time will tell how well they work.

Image credit: “EKG” (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by mgstanton