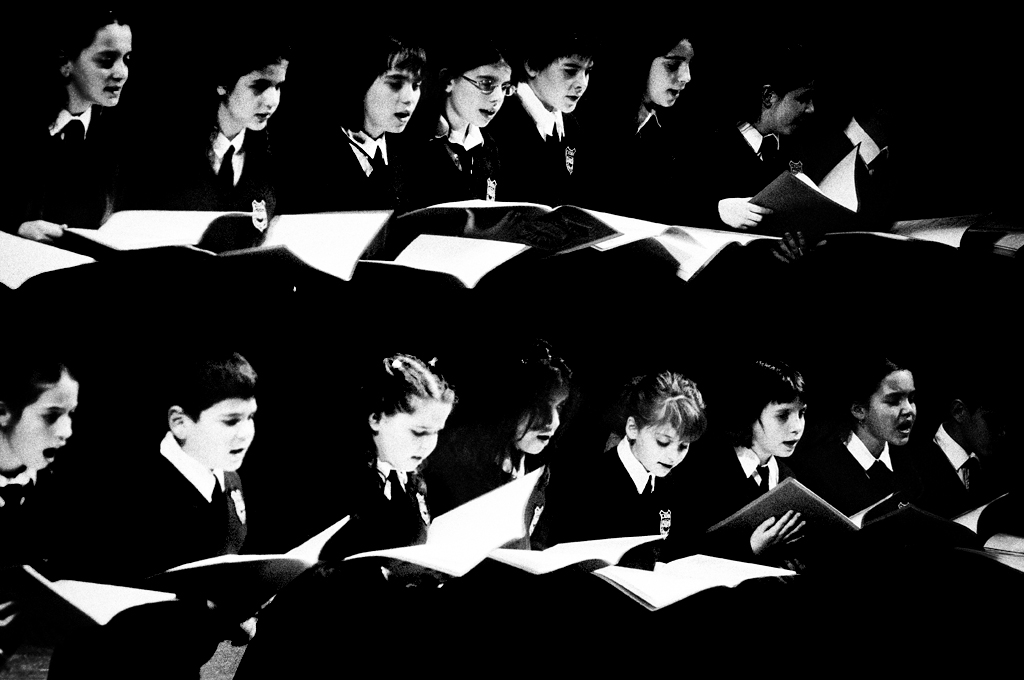

A Sacred Symphony

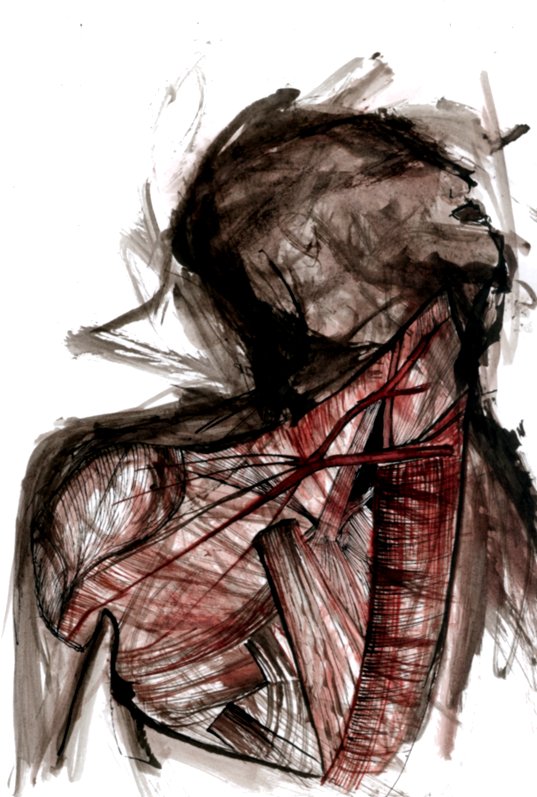

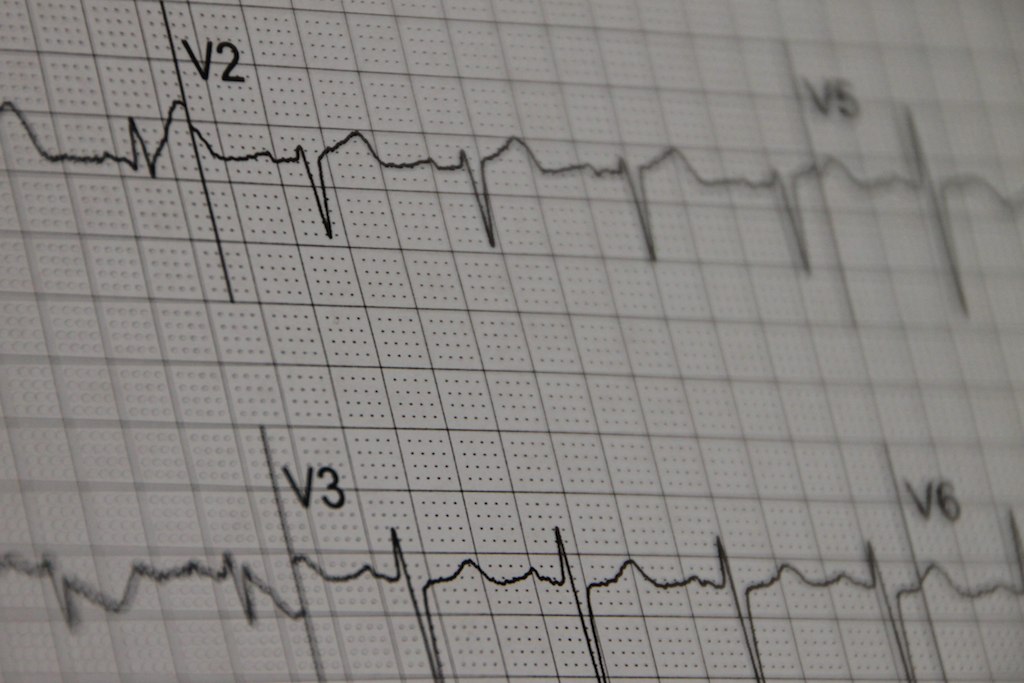

The once-sterile hospital room had become a sacred space, where the raw emotions of love and loss hung in the air. The young daughter, vibrant in her essence but tethered to life support, teetered on the precipice between existence and the inevitable.