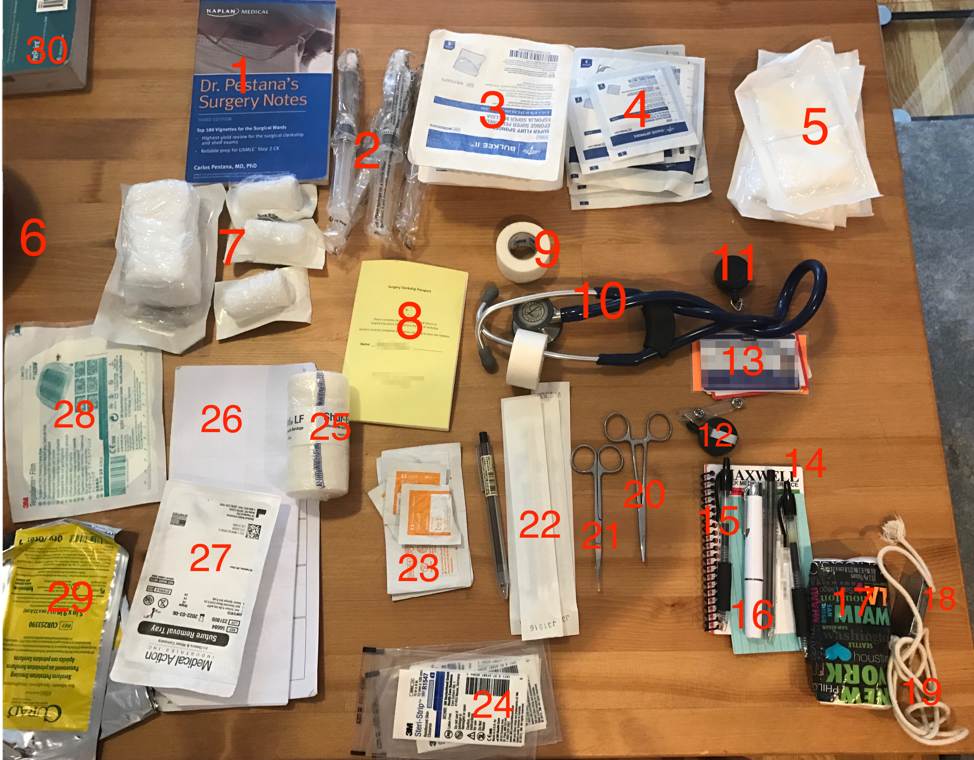

In My White Coat Pockets: Surgery Clerkship

Though the white coat’s role in medicine today is complex — to some, a respected symbol of medicine’s history; to others, a antiquated relic of a paternalistic past — few medical students or frontline residents would deny this emblematic item one major utility: a source of pockets.