This April marked the 10-year anniversary of the founding of in-Training, and we invited all members of the in-Training family to contribute articles and other artistic works to celebrate our first decade as the premier online peer-reviewed publication by and for the medical student community.

Apshara Ravichandran, Class of 2022 at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, contributes this article as an in-Training writer and featured author in our print book in-Training: 2020 In Our Words.

“If you want to understand what a science is, you should look … not at its theories or its findings, and certainly not at what its apologists say about it; you should look at what the practitioners of it do.”

–Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures

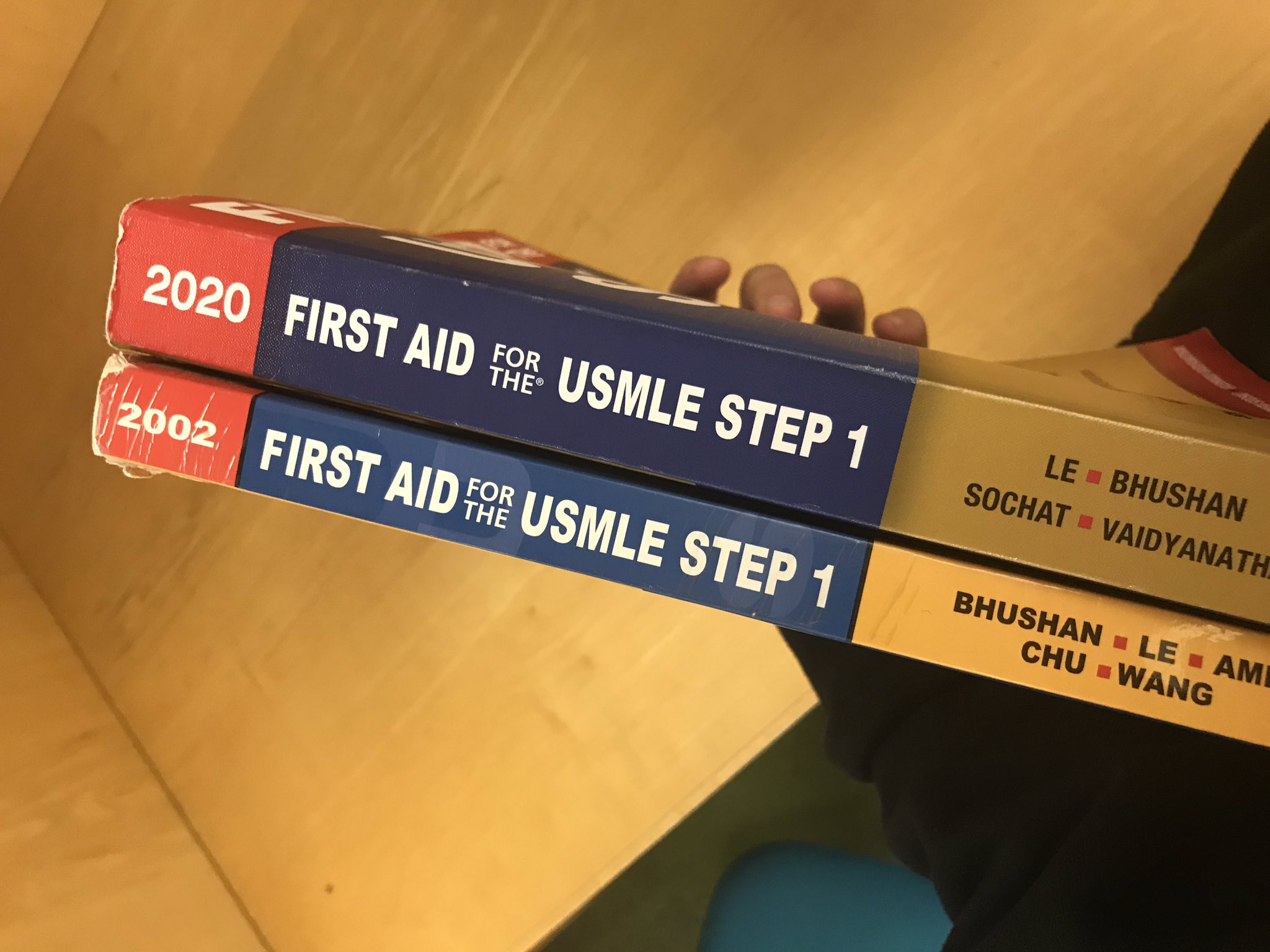

During my Step 1 dedicated study period, I remember looking at these visual comparisons of an early version of First Aid and the most recent edition and feeling righteous indignation bubble up inside me. The former was thin and worn and tattered while the latter was thick, hefty, solid. Hundreds of pages longer, the newest edition felt impenetrable and impossible to commit to memory, expanding yearly with new minutiae to scrutinize.

But that’s what medicine is about, isn’t it? The constant search for explanations, the utterly confident belief that the next randomized control trial might make it all make sense. If we didn’t believe that all these tiny little kernels of repeatable truths, unearthed across the world in New York and China and Australia and anywhere else, were pieces that fit into the bigger puzzle, it would be too soul-crushing to keep digging them out. That’s what we like to believe science is: the unrelenting pursuit of truth.

Truth, at least the truth we learn for multiple choice tests, is gathered from numbers and a physical exam and a thorough history all tied together with what we call clinical judgment. That’s the part they say you can’t learn in a Google search, how those things dance together and tell us the truth. It’s the acidotic blood gas results on the computer screen when combined with the appearance of a tiny, gelatinous baby with arms like toothpicks and a face obscured by tape and tubes.

But there are other things, things beside clinical judgment, that we can’t learn in a Google search. There’s the contempt we might feel when that baby’s mother only comes to see them once in the week since their premature birth, after receiving no prenatal care. What about when you learn that that mom is an undocumented immigrant fleeing their home country? What about when you learn they also were using substances throughout their pregnancy? To be frank, I have never been able to correctly differentiate between 1+ or 2+ edema, but I’ve been able to sit down with moms like this one, and I’ve been present during discussions between providers about them, and I’ve seen people be clinically judged as if they haven’t lived decades of life and hurt and triumph that their doctors know nothing about.

Medical humanity is recognizing that we have always looked at more than numbers, and that we don’t always do so with grace or intentionality. And vice versa, it’s realizing that doctors aren’t blank surfaces but people who carry their own history and hurt and bias into their work. In anthropology, they call this reflexivity: realizing that the truths we’re chasing down are altered, sometimes in the tiniest of ways, by who we are and how we interact with them. Places like in-Training let doctors-in-training openly reflect on the experience of doing this work, beyond the act of interpreting labs and ordering chest x-rays. The field of medical humanities forces us to lean into the subjectivity of this career and acknowledge that we aren’t detached, impartial processors of data working in a clinical vacuum.

We will always need researchers, people who can’t stop asking about gene transcription and who feel at home in a wet lab with pipettes. People who understand numbers and speak the same language as computers that model disease processes. But we also need people who look at a patient and see a story, who look at objective data and see subjectivity, who don’t just do the work of being a doctor but reflect on and study the social, economic, personal, emotional implications of our work. And we need opportunities — publications like in-Training, conferences, medical education lectures, process groups such as those routine in psychiatric training — to center those implications. Medical humanities are vital to keeping the culture of medicine human, for both patients and clinicians.

Image credit: Joanna Watterson, MD on Twitter