For the first time in history, humankind has transitioned from predominantly treating infectious disease to treating chronic disease. These lifelong, quality-of-life-reducing ailments account for 70% of all American deaths and 75% of the United States’ annual health care costs. The proactive approach to reducing chronic disease incidence is through prevention — for example, encouraging those with a family history of hypertension to reduce their sodium intake and those at-risk for dementia to exercise to combat cognitive decline.

However, what if instead of treating piecemeal risk factors, we could prevent the root cause of most chronic diseases?

The incidence of chronic disease is strongly correlated with aging. According to the Information Theory of Aging, aging results from a progressive loss of genetic material due to gradually worsening cellular repair mechanisms. This cellular erosion leads to a nearly interminable list of diseases, including but certainly not limited to cancer, heart disease and neurodegenerative disease.

In his book Lifespan: Why We Age and Why We Don’t Have To, Dr. David Sinclair spotlights the field of aging science and prophesizes a forthcoming paradigm shift in the practice of medicine. David Sinclair, PhD is a Professor in the Department of Genetics and Co-Director of the Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Sinclair discusses how the guiding principle among the scientific anti-aging community is that aging is a preventable and potentially curable disease. By uncovering the molecular and epigenetic mechanisms behind aging, Sinclair asserts that we can delay, reverse and conquer this seemingly inescapable process.

Dr. Sinclair assimilates a body of research that illuminates a cohort of proteins that play a role in the aging process: sirtuins, mTOR, NAD and AMPK. The genes that code for these proteins share similar homology and function across the phylogenetic tree, from yeast to humans. Sirtuins are “enzymes that remove acetyl groups from histones and other proteins” in order to repackage, silence and activate a variety of genes. These worker bees modulate inflammation, energy efficiency and DNA repair. Sinclair details how sirtuins are activated in times of stress, causing the cell to cease haphazard reproduction and focus on repair. The downstream effects of sirtuins are plentiful and powerful: protecting the body from age-related diseases like “Alzheimer disease, osteoporosis, cancer, atherosclerosis, metabolic disorders, ulcerative colitis, arthritis, asthma, macular degeneration and a host of others.”

The mTOR, NAD and AMPK pathways have similar roles and are related to energy efficiency and cellular/DNA repair. Aging distorts these pathways, resulting in age-related diseases. These pathways are ordinarily activated by stress; seeing as a stressful environment communicates to the body to cease cellular reproduction and to repair itself. Since these pathways are involved in cellular repair and govern the aging process, by finding ways to modulate these pathways, we may be able to combat aging at the cellular level.

Sinclair compiles a large body of literature on the process of hormesis — a regenerative state induced by carefully exposing the body to a controlled amount of stress. Some of these hormetic tools are calorie restriction, intermittent fasting, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and cryotherapy. Similarly, researchers have identified an array of pharmaceuticals that trigger these anti-aging pathways, including metformin (a diabetes drug that controls blood sugar levels), resveratrol (an antioxidant found in grapes/wine) and NR/NMN (precursors to NAD).

Sinclair concedes that there is a dearth of attention and resources being allocated to anti-aging research. He argues that the chief reason that these anti-aging considerations have yet to receive a spotlight is that aging is not classified as a disease itself. By shifting the concept of aging from an insurmountable inevitability to a solvable inconvenience, it is possible to initiate the institutionalization of anti-aging medicine. One of the best places to start this change in semantics would be at the level of undergraduate medical education.

Undergraduate medical education is at least partially receptive to the shift from acute disease treatment to chronic disease management, but the resulting implementations have seen mixed results. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) cites how medical schools are integrating instruction in geriatrics, pain management and palliative care to better prepare medical students to combat the growing prevalence of chronic diseases. Similarly, in recent years there has been a growing emphasis on the social determinants of health. In 2015, the MCAT was updated to include behavioral and social science sections in the hopes of procuring future physicians with strong behavioral management skills.

Although these adjustments are well-intentioned, they continue to evade the root cause of age-related issues and most chronic diseases: aging itself. It would be advantageous to integrate aging pathophysiology and anti-aging interventions early in the training of a physician. As medical schools begin to more fully integrate preventative medicine into their curriculum, it would be worthwhile to include sessions on anti-aging practices.

One of the most striking findings discussed by Dr. Sinclair is that many of these anti-aging interventions are widely accessible lifestyle interventions. It may be beneficial for medical schools to encourage students to self-experiment with these lifestyle changes to experience the benefits organically. I have personally tried out forms of intermittent fasting and HIIT and have noticed improvements in my energy levels, mental clarity and metabolic biomarkers which are consistent with the literature showing similar results. A shift in the traditional medical curriculum would help organically reposition the cultural climate around aging from a widely-accepted certitude to a preventable process, engendering more attention and funding to the field, allowing for a clearer understanding of the related pathways and the discovery of more fine-tuned interventions.

Dr. Sinclair provides insights that challenge the future of the health care system. The implications of this research shape best practices in medicine as well as the ways in which clinicians should be trained. Altogether, Lifespan is an easily-digestible, curious window into an encouraging future that merits a read by any current or future clinician.

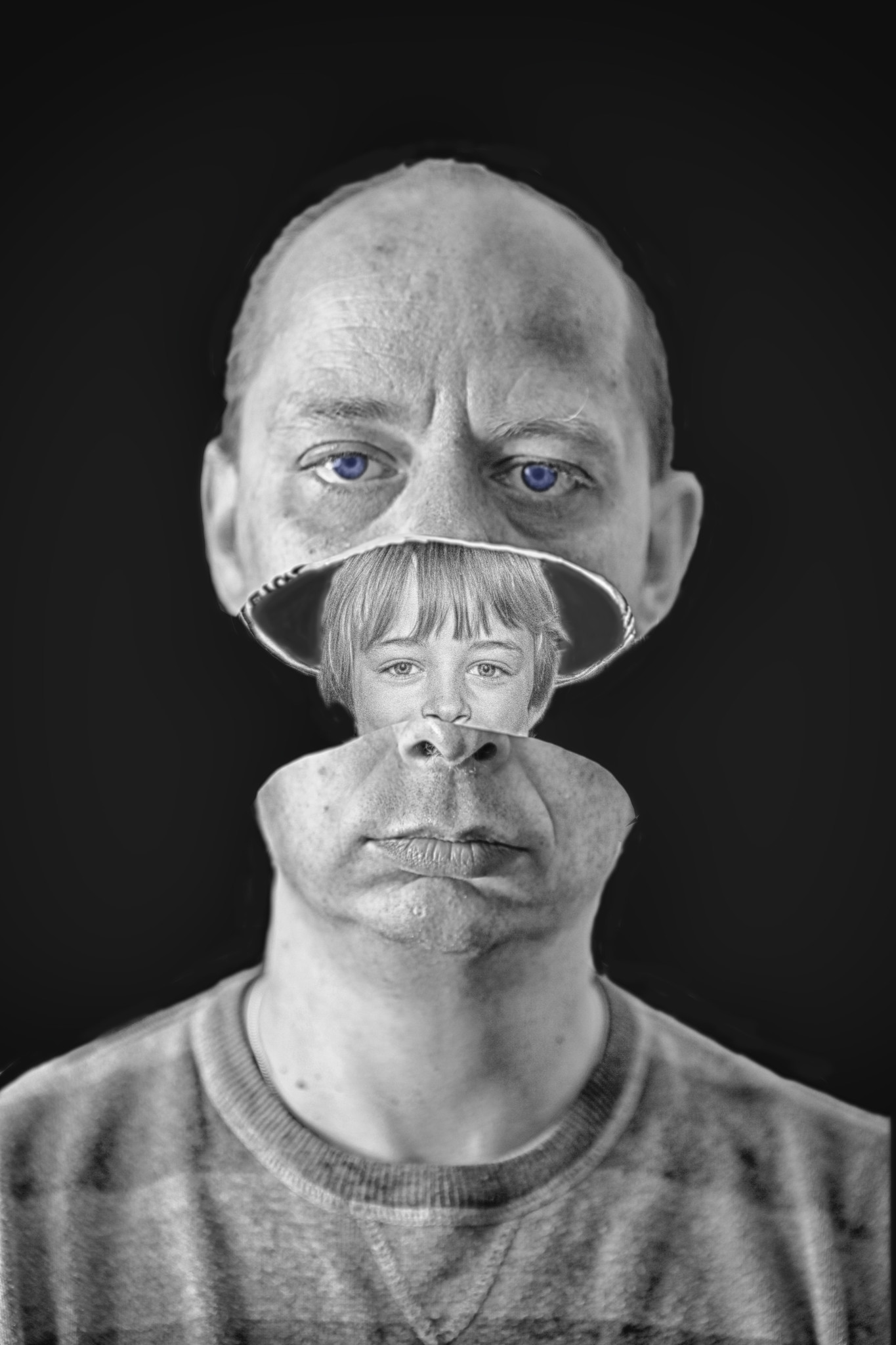

Image credit: Old & Young (CC BY 2.0) by rockindave1