When I told my aunt I was going to medical school, she looked me up and down and said, “So you’re going to be a know-it-all.” This comment took me aback at the time but I now realize it was in fact a revelation that could be pronounced upon anyone embarking on this mystifying snarl of a career path.

You learn quickly in the first year of medical school that facts can be traded for respect — a professor’s nod or a grudging “they’re so smart” muttered from one peer to another. Acronyms, lab tests and Latin names become intellectual capital, the more obsolete the better.

So each day you open your skull flap and shove in as much knowledge as you can, all the while hoping you’ll be able to zip it back up. You begin to feel like an overfilled suitcase, constantly debating whether you can manage more easily without the last pair of underwear or your favorite socks.

And yet, there are moments that make you pause in your packing. That set you back on your heels and let cool wind whirl just beneath the curve of your forehead.

Like when I lifted a cadaver’s arm to study the complex arrangement of tendon and muscle and saw she was wearing nail polish. The color, a florescent pink with tiny orange flowers, barely chipped, brought me back to a walk on the beach and white wings against blue.

Or when we had a patient panel of parents and their children born with a life-threatening congenital defect, and one six-year-old girl with a cloud of white-blond hair spent the whole hour running up the lecture hall stairs and swinging upside down from the railing. Her irrepressible energy spoke more eloquently to childhood amidst illness than any of the words.

Or the day I learned that my heart was so difficult to find on ultrasound because it is located not on the left side of my chest but squarely behind my sternum. A fact that would, my instructor offered brightly, make chest compressions that much easier should I ever need them.

But most of all, when I shadowed at a pediatric clinic and listened to a mother explain how her baby, a toe-sucking buddha in a onesie the shade of a melted Creamsicle, would not drink her breast milk. Her doctor recommended testing, which revealed high lipase.

“Then I went home and tried it,” the mother said, her omission to drinking her own breast milk so casual that, at first, I thought I must have misunderstood. “It was foul,” she said, “Poor guy. No wonder he wasn’t drinking.”

As she explains how she now blends her breast milk with bananas to feed to her baby, the ultimate natural smoothie, a wind is again whirling in my head, stirring up new thoughts.

That I am an adult woman who has never considered that breast milk would vary from woman to woman, in taste and composition. That it would not be uniform like the half gallons lining the grocery store fridge, expiration date stamped in block letters.

That mothers are strange and wild beings whose actions at times are so mundane you forget their true fierceness.

That there are many types of knowing. Telling someone their milk is high in lipase is an example of one type, the kind where poor infant feeding is translated into lab values and decimals.

But — and often I forget — that is not the only kind of knowing.

There is the knowing of this mother. A caregiver who needed to find out what high lipase tastes like in order to feed her child. Who drinks her own breast milk. Who learns to add bananas.

The kind of knowing that reminds me that each patient is not a lab value, and every problem is not solved with procedures or medication. That shows me the best physicians are not overfilled suitcases or unquestioned savants. And that the best sort of knowing, like the best sort of science, leaves room for discovery and for awe.

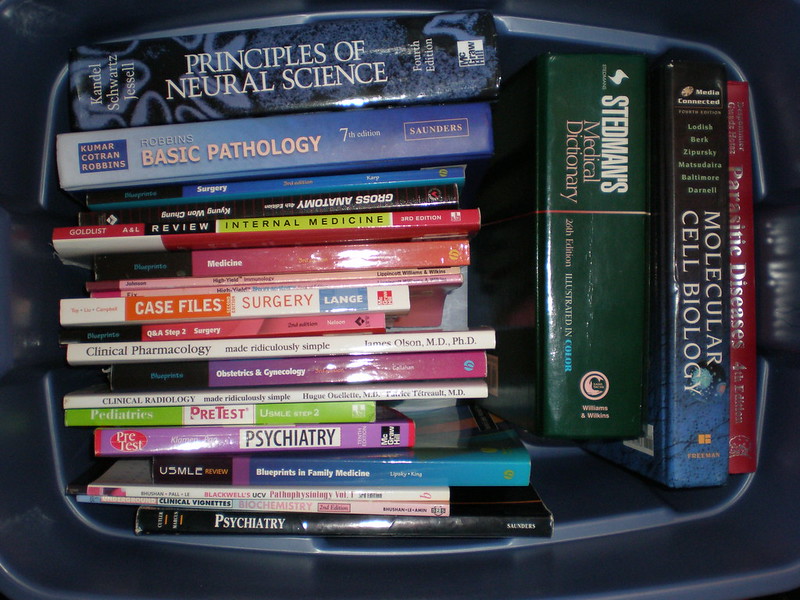

Image credit: box of medical textbooks (CC BY-SA 2.0) by pmccormi