The beauty of medicine is that we are trained to see each person as an individual, not as a victim of their stereotypes. We are taught that we are more than our skin color, our religion, our clothing or our gender. But even though I see more than a patient’s demographic on static paper, those same patients, and sometimes even colleagues, fail to see me as more than just a woman. My capabilities as a physician are constrained under the unisex scrubs that sit too loosely on my body, hiding my gender identity. But no matter how much I try to hide what I look like and focus on who I am on the patients’ care team, my womanhood always equates to “nurse” in their minds.

People have always told me that being a woman in medicine would be hard, but I never listened. I knew that did not apply to me because I was stronger than the shackles of my gender’s stereotypes. I was hardworking and demanded the presence of the room; I would never be just a woman. But I was proven wrong every single morning when I walked into a patient’s room and was asked why the nurse was bothering them so early. The first several times, it was easy to shrug off. Maybe I was too passive, maybe I did not mention who I was or maybe I looked like someone else. But after seeing a patient for two weeks straight and stating that I was a medical school student almost every time, being called the nurse was more than just coincidence. My actions were not to blame for their inability to understand, but my body and long hair were.

Patients could be forgiven. They are in one of the most stressful periods of their lives. As they lay in a hospital bed, the weight of their diagnosis is more important than the status I carry. The constant movement of people in and out of the room leaves the patient confused, in a flurry of white coats, fighting to recall all the information they hear. Physicians, however, do not have the same luxury.

Walking into the surgeons’ lounge will always be nerve-racking. By the third or fourth time, I realized my emotions did not matter because the surgeons did not acknowledge them — they barely acknowledged me. I was the only woman in a room full of male surgeons and I was nothing. I stood next to my male colleague every day and watched as the surgeon’s gaze only met his eyes. All the lessons being taught, the words of wisdom, only directed towards the male student, never towards me. I blamed myself yet again. Maybe I was not working hard enough, maybe I did not know enough, maybe my interest was lacking. So, I spent the evenings reading and preparing for the next day, making sure my intelligence was not the barrier to me being seen.

Bright-eyed and ready to perform, I walk into the surgeons’ lounge, prepared for any questions that might be asked. Question after question, I answer correctly, showing my hours of hard work. But every answer fell on deaf ears. Not a comment, not a look, not an acknowledgement was given. The room went quiet as the next questions went unanswered. Finally, my male peer spoke up and answered a question correctly. He was rewarded with praise and acknowledgement for being able to answer “such a difficult question.” He sent a sad look my way, as if apologizing for the bias placed upon him.

It was then that I realized. I wanted to be angry. I wanted to fight back against the inherent system I was born into, but I was just defeated. I realized that no matter how much I knew or how hard I worked, I would never be good enough to be in an operating room. It was not my inability to perform but rather my inability to be anything other than a woman. I was tied down by my appearance and name. I was insufficient as a doctor because I did not look the way men do. My knowledge was not under my white coat … underneath was only a female body.

What they see first is my gender. They see a woman who is made only to care for others but never to think. They see a woman who is supposed to be submissive and listen to what those above her say. They see a nurse, even when my white coat and badge say “medical student.” What they see first is what they want to see and not who I am. They do not see the hours spent combing through charts, reading articles and studying for their health — all to be a better physician.

Even with how hard it hurts to feel like I am less than my colleagues, I wake up every morning and put on my white coat and a smile. I continue to take the lessons that are taught and add them to my toolbox to make myself better. I have come to realize that I can never be anything else. And I do not want to be. I want to be the best version of myself, in my female body. I want to be a better physician and that is not limited by my inability to be a man. I will not change my approach to medicine just because I need to be more like them.

But even with the restrictions society puts on my gender, what I see first is a woman who can be both caring and confident. I see a future physician who deserves to be respected and deserves to be seen for who she is. What I see is a student who continually wants to grow and be better than she was. I am a woman. And I am a woman who will continue to push through all of the adversity to make an impact in a patient’s life.

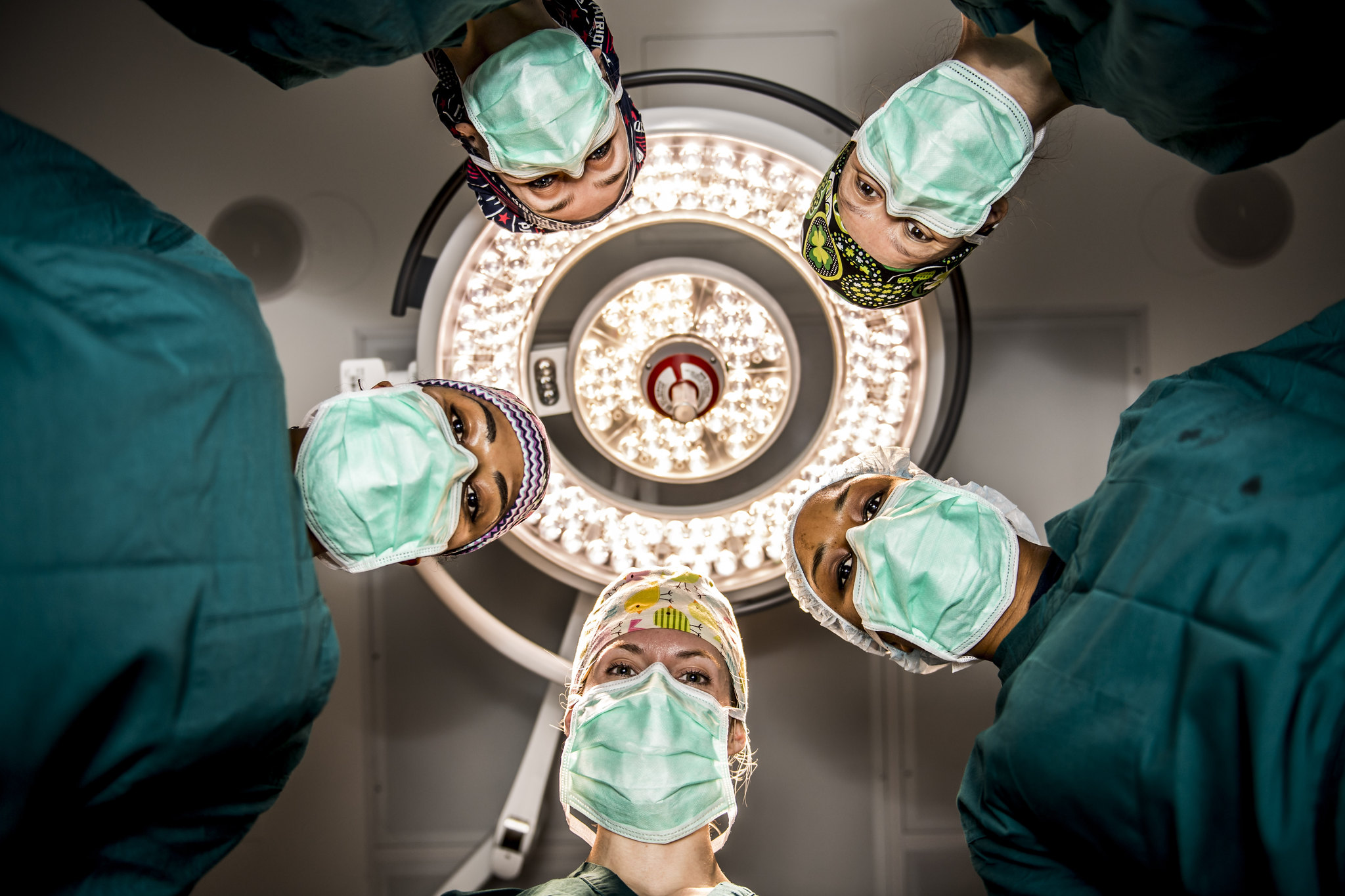

Image credit: Belvoir Hospital female surgeons display (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Fort Belvoir Community Hospital