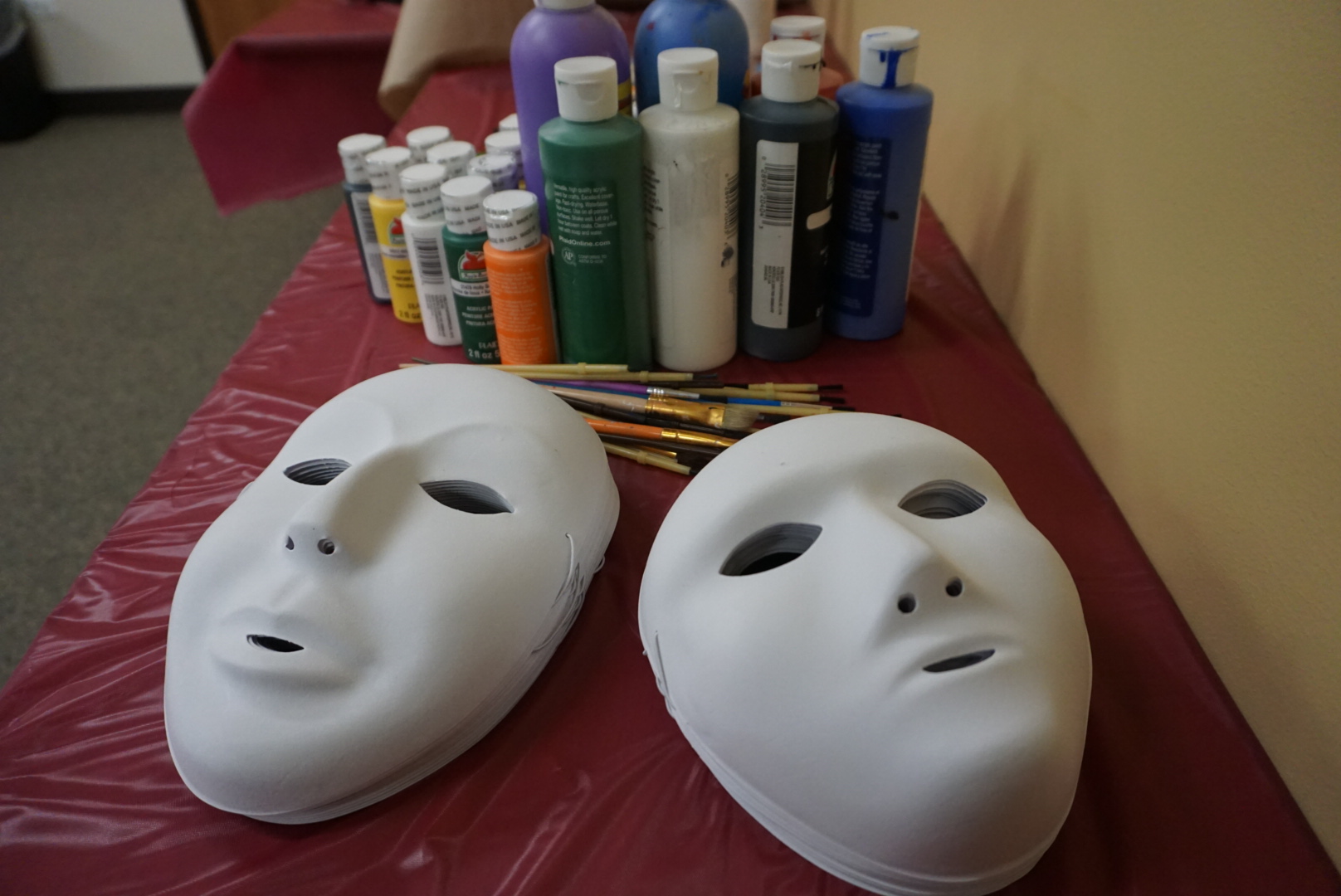

On a December night in a northern suburb of Chicago, the weather outside dipped into single digits with a sub-zero wind-chill. Safely situated indoors, a group of medical students wandered into a classroom where tables were covered by plastic tarps and laden with pipe cleaners, acrylic paint and brushes and a stack of blank masks. Licking the emotional wounds left by a sleep-deprived exam week that ended only three days prior, the students eyed the art supplies. They were hopeful for a means to reconcile their psyche tattered by cold and a semester of school and were in this room for an event that promised an introspective experience. The event was a mask-making art therapy session, and I was the host.

Months before this cold night, I came across an article describing the concept of art therapy through mask-making. Intrigued by the idea, I reached out to the event coordinators, Melissa Walker and Dr. Mark Stephens. They provided insight from their experiences and perspectives while wishing me luck as I started preparations to hold my own version of the event.

The event centered on ideas of identity, and the masks served as a terrific vehicle of this theme. The inner and outer aspects of each mask allowed for the option to depict the tension between our personal and professional identities. This was not a self-portrait exercise in the physical sense but rather an exploration of our identities.

As medical students, we are in a near constant state of pursuit. We are driven individuals set at the end of a vast wasteland known as the curriculum. Yet we lack any real sense of control. Bounded by exam dates, we don’t control what we are taught but rather the hours in a day we devote to the subject. My hope in hosting this event was to deliver a sense of control to the participating students. The masks were a blank slate to which the student could apply as much or little color, what color and what material.

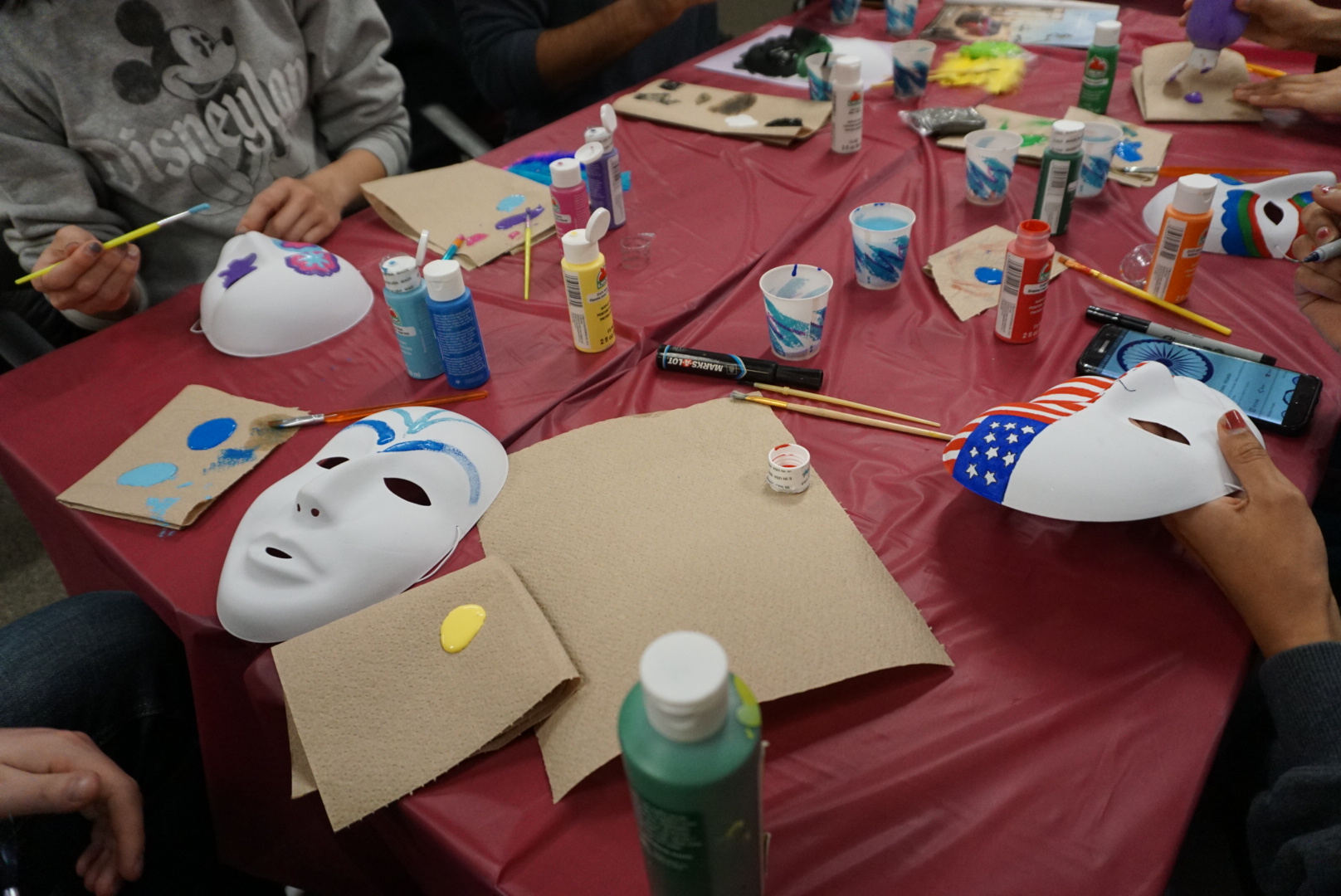

Over the course of the ninety-minute event, the students tossed glitter around and blended new colors of paint on makeshift palettes. For almost every student (except one girl who was remarkably active with her painting hobby), this was departure from the normal nightly routine of lectures and notes.

Near the end of the event, Dr. Mark Stephens video-called in and lead a group discussion about the masks and what they represent to us. We each provided a one-word description for the event and out came the responses: “layered,” “subtle” and “relaxed.”

This event was vital for students because it forced us, even for the briefest of moments, to confront ourselves. Prior to medical school, each of us had a foundation of memories and experiences that culminated our identity. We do not lose ourselves in some apocalyptic-fashion when we start classes, but the daily classroom battle of retaining information and the perpetual sense of overwhelm chips away at our carefully cultivated identities. Looking at the mask and deciding what to paint necessitates introspection.

From my observations, there were few students who immediately jumped into painting knowing exactly what they would do. Inherent in our decisions there were questions we first had to answer. “Who am I” is where some may have started, but such a vague entry point gave way to more pointed questions like: “what is important to me,” “when am I happiest” and “what am I really good at doing?”

The questions gave us the opportunity to reflect. To quote one of the participants, “when I remember who I am and what I’ve been through, I feel stronger. This was recollection and exploration as a means of building resilience.”

“The concrete image of the mask unleashes words.”

I knew that the event had merit for the individuals participating, but also that there had to be a larger component. After the event, I turned to one of the students that participated and tried to construct an answer. The two of us discussed how we as individuals act within our class. The subject of barriers was a heavy component of this discussion because physically, we are separated by notes and screens. The separation only widens as we emotionally seal ourselves off from each other. We can spend hundreds of hours in class together and form study groups with a small number of people, yet know little about them.

Since this event took place in the realm outside the curriculum, the ever-present barriers of equations and highlighted texts were absent. Instead, we were left with paint brushes and packets of glitter. Instead of comparing answers, we were comparing color schemes and patterns. During the event, students wandered around observing their classmates’ masks and were able to visualize the otherwise-obscured identities that were now revealed in brilliant colors and fantastic patterns. The primary objective of the event was the investigation of the self, but in doing so we displayed ourselves for classmates. To me, this display of the self was a terrifying, but ultimately necessary, act of exposure. A satisfying curiosity filled me when I looked around at my classmates’ masks. I was seeing the literal surface of the people with whom I spend countless hours.

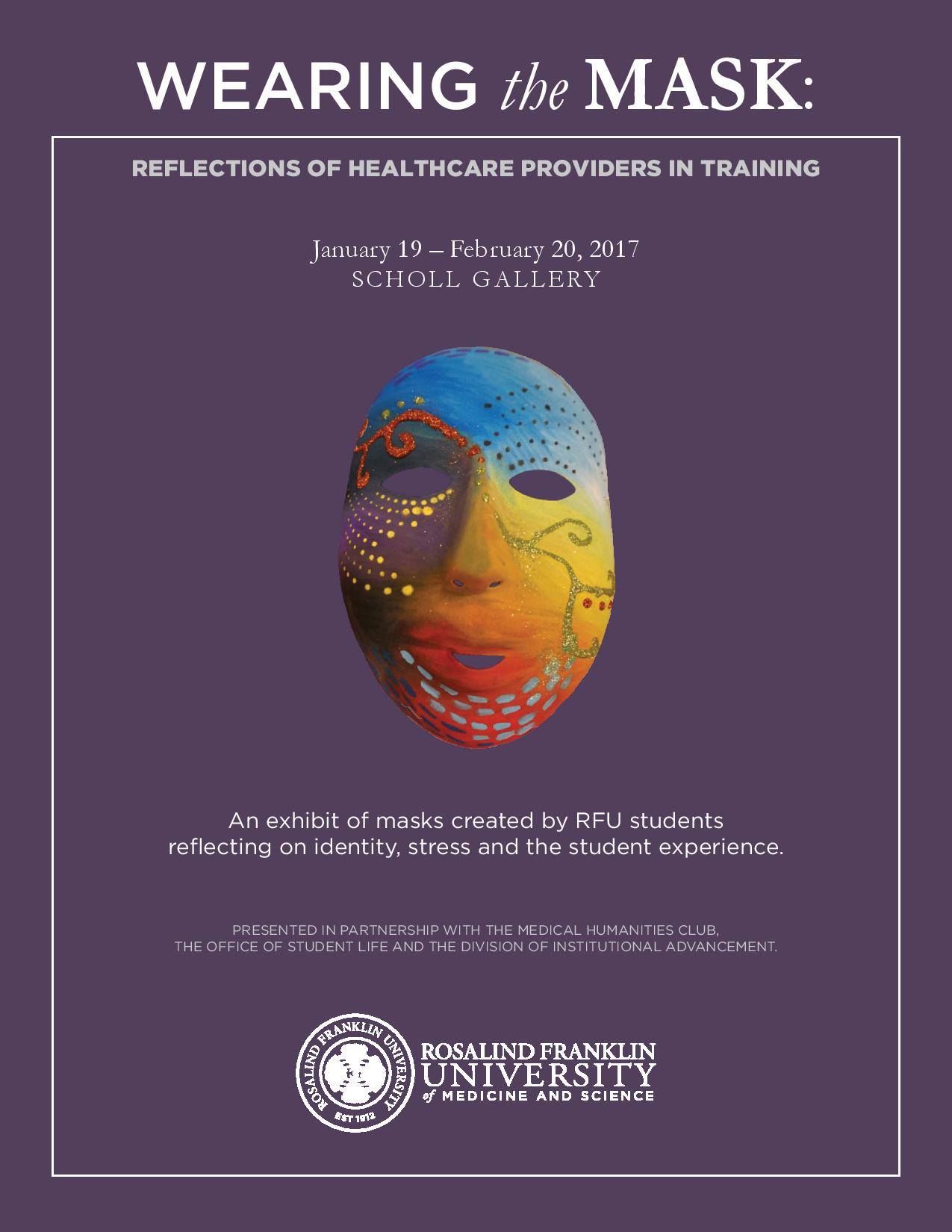

Our school chose to display an exhibit of the masks in the on-campus gallery. Faculty, staff, and students alike were able view the anonymous works. I hope that the few minutes spent in the gallery instilled a faint sense of appreciation for the creative streaks that drive the individuals making up our class, school, and profession.