“The curse of knowledge,” christened into the psychology lexicon in 1990 by a graduate student at Stanford, refers to the human tendency to assume that others know the same things that we do. We often get in our own way thanks to this thinking error; in incorrectly believing that everyone around us is on the same page, we spend precious time reinventing wheels and swimming upstream in personal and professional problem-solving.

Medical educators have been teaching students about this roadblock in the context of patient communication for years. In the preclinical curriculum we learn how to take a medical history and how to thoughtfully discuss medical care in a patient-centered way, an undeniably important skill. Through workshops and practice with standardized patients, we learn to ask more often than tell; we try our best to meet our patients on their home turf. Rather than assume that we have the same understanding at the start, my peers and I have learned to begin patient conversations with a variation of the same question: “Can you start by telling me what you already know?”

Interestingly, despite how ingrained this habit has become for many of us when working with patients, we drop the baton with our colleagues. Time and time again I find myself starting a conversation without first determining if there exists a context other than my own understanding, and consequently reach different conclusions than my colleagues — and I know I’m not the only one. Between the two or more busy services managing a patient’s hospital admission, we often lack the time to deliberately inquire where others are coming from. “What do you already know about our patient?” is not a question routinely or explicitly emphasized in the everyday reality of health care. Compounded with the curse of knowledge, this can lead to contradictory messages being conveyed to a patient.

During my pediatric rotation, a little girl was brought to the ED the day her family was set to leave for vacation. Her physical exam and imaging confirmed a ruptured appendix that would require surgery and almost a week of IV antibiotics, meaning our patient would miss her family’s forthcoming vacation. Our team of pediatric faculty, residents and students broke the news as our patient looked longingly at the summer sunshine outside. Her disappointment was palpable, but we felt it would be a failure on our part if we discharged her only to have her readmitted in a few days with a complicated infection.

Just after this extensive conversation with our patient and her family, a discharge summary from the surgical team appeared in the chart. Confusion quickly set in for everyone — patient and family included. After a game of telephone tag between pediatrics, surgery, nurses and our patient’s family, we finally understood one another. The surgical team explained that while they agreed that a course of IV antibiotics would be standard, our patient was recovering remarkably well; it also turned out that the surgery team knew something we didn’t.

The family would be vacationing mere moments from several well-known pediatric care centers, so it was conceivable for our patient to be discharged to enjoy the last days of her summer with the understanding that she needed to report to one of those nearby care centers should anything change. The surgery team was thinking outside the box and empathizing with our patient in a different way than we were. Despite the best of intentions, cognitive bias from the curse of knowledge had interceded to lead our teams in the direction of opposing discharge plans.

Thankfully, this miscommunication was easily resolved, though it is easy to imagine situations with more dire outcomes. Together, as a combined surgical and pediatric front, we discussed both viewpoints with our patient and her parents. Later that day she was happily and safely discharged, and our teams had mutually benefited from the opportunity to explore the question we should have been asking each other in the first place: “What do you know already?”

I have learned during preclinical years and clerkships that, unexpectedly, it can be an advantage to be in the dark. Escaping the curse of knowledge requires taking a stance of curiosity towards what our peers might already know that we do not, and vice versa. As future physicians, it will be important for us to continue our progress in breaking our curse of knowledge with our patients, but the next step is one that is not quite as obvious: breaking it with our colleagues as well.

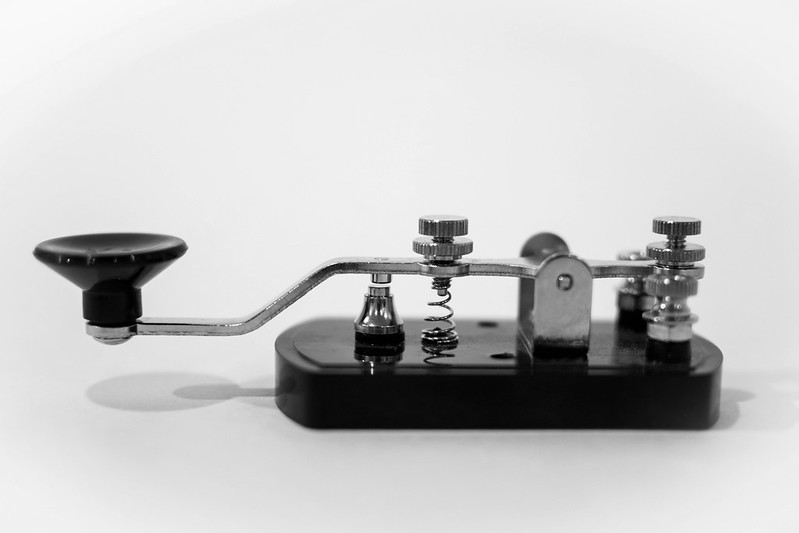

Image credit: Morse code (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Eric.Ray