When I tell people I am studying medicine and hope to be a surgeon, there tends to be a general agreement that I have made a good career choice, I have chosen a respected, solid field of work and will be guaranteed a “job for life.” Since the beginnings of mankind, there has been illness, and thus, there is always a need for healers. Doctors will always be needed, or so we have been led to believe.

In the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE), it is not strictly true to say you will always have a job. In fact, you might not even get off the starting block. Last year, the Irish health authority quietly admitted that they did not have enough intern posts to meet the demand from medical graduates in Ireland.

I am a second-year medical student and I am hoping to pursue a career in neurosurgery. I am blessed to be based in Ireland’s top hospital for neurosurgery, learning from the very best the country has to offer. I have a previous degree in general nursing, a post-graduate qualification in tissue viability and years of experience in both the public and private sector. I have experience both writing and editing for a wide variety of medical blogs and journals. On paper I sound like a solid-enough candidate, but in reality, I have already made peace with the fact that I will be moving abroad after qualifying and it may be many decades before I am in a position to move back home to Ireland.

In 2015, 1,100 medical students graduated from Irish medical schools. In the same year, there were only 727 intern posts available. Medical students are required to complete an internship here before they can get a Certificate of Experience required by the Irish Medical Council to register and move on to specialist training. Of the 1,100 applicants applying for posts in 2015, 784 were Irish or European Union (EU) citizens from Irish medical schools, 291 applicants were non-EU citizens who have studied in Irish medical schools and the remaining 22 are Irish or EU citizens who have completed their studies in an overseas medical school.

Irish-trained medics are not all going to get an intern post, never mind vying for intern posts in competitive specialties. The HSE gives priority to medical graduates from the European Union who have applied to post-graduate programs through the central applications office. With more potential graduates, it makes sense that there needs to be some sort of filter system in place. But is it fair that our current filter cuts out international graduates, who are already paying higher fees? The lack of consideration of how some international students may be performing better academically than their EU counterparts naturally creates resentment among international graduates who must feel let down by a system they’ve spent years investing their time and money in.

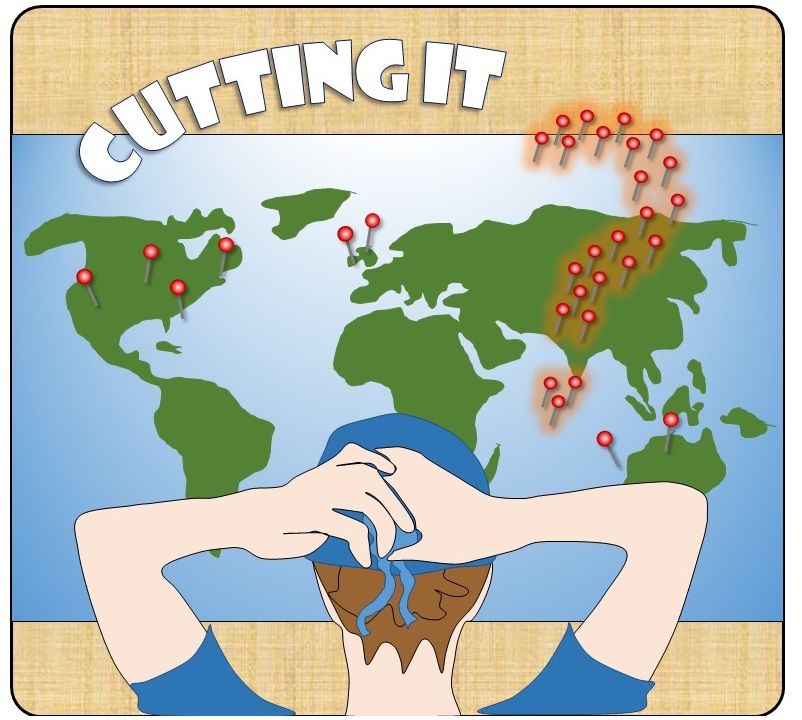

At the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, my class of nearly 300 students is predominantly made up of international students. My classmates come from all over the world: the United States, Canada, Malaysia and Emirates are particularly well represented. They are subject to the same standards as the rest of us. We all sit for the same exams, perform the same OSCEs and complete the same number of clinical hours. My classmates are some of the smartest individuals I have ever met. They are truly good, hardworking people and we all share the same dream of becoming great doctors one day. It saddens me to think that from the very beginning, some of us are already at a disadvantage.

My international comrades, for the most part, take the situation as an inevitability. They expect to leave the country they’ve made their home for four years. They expect to uproot the lives they’ve created for themselves and either return to their home countries or perhaps go elsewhere so that they may have a fighting chance to work in the career they’ve spent years working towards. I respect and admire their ability to circumnavigate the globe as they explore their post-graduate options; I was not that brave at 23. For those of us who have slightly better odds of receiving an intern post, the struggle is only beginning. Interns begin their burgeoning career within the Irish Health Service working long hours at the coalface of medicine, which continue even after completion of the intern years.

In an effort to help my international colleagues and Irish students planning for post-graduate training, my next column will look at both the training pathways in this country as well as examine training schemes abroad, namely in the US, UK and Australia. I will be looking at how an international student can go about getting on competitive schemes as well as considering ways to get the most out of electives and preceptorships abroad. I also hope to interview both students who have completed training abroad, either as international students who are working here in Ireland or Irish trained medics who are now working in the States or Australia.

My hope is that this column will provide support for students who are wondering where they will end up in their career. I hope that by helping each other engage and learn about other cultures and the health systems we will all become global healthcare professionals, confident enough to work in any country in the world.

A medical degree offers students a global skill, where they can work anywhere in the world. But in reality, how easy it is to leave one health service for another? Join Suzanne as she navigates studying in Ireland while planning for a surgical residency abroad.