“A hoop was put up without clear, convincing evidence. This hoop causes students massive stress and anxiety, and almost everyone goes [through] it without difficulty. So why do we have this hoop?”

–Christopher Henderson, fourth-year medical student at Harvard Medical School

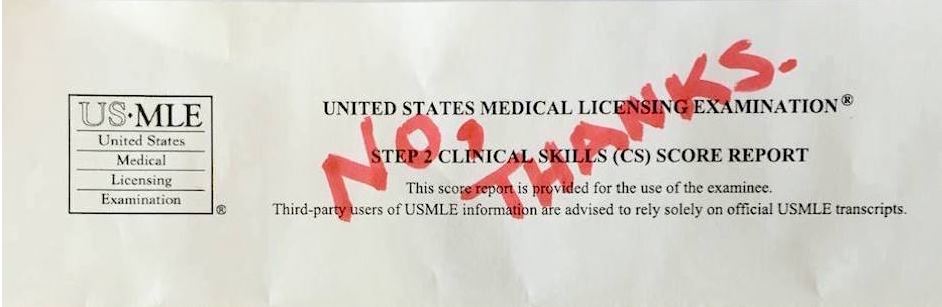

In March 2016, six medical students at Harvard Medical School launched #endstep2cs, an initiative aimed to garner support for the termination of the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) that is currently administered to medical students prior to graduation. This past week, we talked with Christopher Henderson, one of the organization founders, and Dr. Peter Katsufrakis, the senior vice president for assessment programs at the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME), to discuss the faults and merits of both the CS exam and the student-led initiative to end it.

What is the Step 2 CS Exam?

The USMLE has established four exams that are required to be completed by medical students that hope to carry an MD within the United States, wittingly labeled as Step 1, Step 2 — which is broken up into a Clinical Knowledge written exam and a Clinical Skills practical exam — and Step 3 (often taken during residency). Every year, medical students around the country prepare for Step 1, the unofficial measuring stick for residencies. This score can make or break your hopeful, budding career. It makes sense then, to invest months preparing and thousands of dollars in study aids for the $600 exam. However, as the national average for Step 1 has slowly crept up, residency programs are looking towards the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) to help distinguish qualified students. A counterpart to CK, the Step 2 CS exam, was launched in 2004 as means to measure the clinical skills of medical students prior to licensing and graduation. The exam consists of twelve 15 minute practical standardized patient encounters each, followed by a 10 minute period where students must complete a patient note. Examines are assessed in three main components: communication and interpersonal skills (CIS), Spoken English Proficiency (SEP) and the Integrated Clinical Encounter (ICE), and the final grade is reported as pass/fail.

The Petition

The #endstep2cs petition was started by fourth-years Christopher Henderson, Benjamin Rome, Lydia Flier, Benjamin Brush, Carolyn Treasure and Samia Osman at Harvard Medical School. The petition highlights two major concerns about the current USMLE Step 2 CS exam — that the exam adds an unnecessary financial burden and that it does not have value for medical students attending U.S. medical schools.

The Expense

The USMLE Step 2 CS is a $1,275 exam that is located in only five cities around the United States. This means that students need to spend thousands of dollars on travel (often times including plane tickets and car rentals), hotels and registration associated with a test possessing a 96% first time pass-rate for graduates of U.S. medical schools and a 84% pass-rate for repeat test takers. This cost is amplified further for non-contiguous American students: imagine the expenses for those living in Hawaii, Alaska or Puerto Rico. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013 estimated that when one looks at the ~17,000 individuals who take the test each year, it costs nearly $1.1 million dollars to detect just one person who will completely fail the test twice. Henderson and his colleagues argue that this is the key problem with the CS exam, especially when taking into consideration the fact that medical students graduate with an average debt of $166,750 in conjunction with the data showing how poor the exam is at identifying weak students.

When I raised similar points to Dr. Katsufrakis, he remarked that, “From the perspective of a medical student, it looks expensive for the reasons you’ve described, but from the perspective of the public, the requirements of the clinical skills examination may well fall below what some members of the public would expect we would require of students pursuing a licensing examination.” Dr. Katsufrakis also argued that while “exams are expensive,” they are an integral part of every field, including pilots, accountants and lawyers. Additionally, the series of licensing exams doctors must pass is not extraordinary compared to these fields.

When talking about the balance between the need for standards and the burden of cost, Henderson said this in favor of ending the exam:

“Okay, if [the USMLE’s] goal is to see, to check that things are standardized and the vast, vast majority of students pass on their first time and virtually everyone on their second attempt, it’s not as though the exam is catching that many people who, by the USMLE’s judgement, [are] deficient. And even if it is, it’s not worth a million dollars a head. That is a horrendously poor value. If this was a medical test, if you were checking for cardiac ischemia or something like that, you would never apply test with this kind of sensitivity and specificity and cost, you would never do it. But we have to do it every single year … and we believe that is a poor value proposition.”

An English Exam?

Prior to 2004, only foreign graduates had to pass what was then known as, the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) Clinical Skills Assessment. Thus, since the ECFMG was incorporated within the CS exam, many opponents of the exam argue that it is an English competency exam, and that it is therefore not only easy for U.S. medical school graduates, but rather a method to weed out foreign medical school graduates (FMSGs) based on English proficiency. Dr Katsufrakis disagrees, however, arguing that “the assumption is that graduates of international schools fail on the basis of their ability, or lack of ability, to speak English. But in fact … the failure rate from the spoken English proficiency part is actually fairly small. The greater proportion who fail, fail for other reasons.” And, this is true — beyond just being able to communicate with patients, the CS exam ensures that doctors graduating from very different medical schools all across the country and world, have, to some degree, a standardized assessment ensuring they can gather a proper history, conduct a correct physical exam, generate a differential diagnosis, organize their thoughts in a matter that can easily be shared with others unfamiliar with the patient — and yes, communicate in English.

Further, when addressing the the idea that the exam is easy for American medical students because U.S. medical schools already train students in, and assess, the components evaluated by the Step 2 CS exam, Dr. Katsufrakis says that those arguments don’t “recognize the literally hundreds of students who fail it. Who absent the examination … [who would be] allowed to go on in their medical careers … with what are deficient clinical skills.” Dr. Katsufrakis argues further that the success of the exam is not merely seen in the context of the people it identifies as weak in the components it assesses:

“And that doesn’t even measure … the impact of the examination on the students who, knowing they are going to have to take the examination, study, prepare for it, develop their skills in a way so that they are prepared to pass the examination. So the impact of the examination is probably even greater than what is measured by the students who need to repeat the examination, but even if we just look at that number it’s still substantial … The students coming from medical schools outside the U.S. fail in even greater numbers and thus the examination provides a pretty significant protection to the public against the individuals who would otherwise not have demonstrated their clinical skills necessary to practice medicine.”

When this idea was posited to Henderson, he countered by saying,

“We want students and future doctors to be clinically competent. We further believe [in] having national standards in the case of other licensing exams, and frankly that everyone has to measure up to the same yardstick in some capacity, we think that is very important. We also think that the mission of these organizations, which is to protect the American public … that is an important mission and one that we fully support. But in this specific case with this specific exam, value calculation does not justify its existence for U.S. medical graduates.”

However, multiple studies have shown that components of the Step 2 CS exam do indeed predict successful future physicians. A 2016 study from Academic Medicine claims that of the factors evaluated — USMLE Step 2 CS data gathering and data interpretation scores, history-taking and physical examination ratings — the Step 2 CS data interpretation scores were positively related to practical supervised history-taking and physical examination ratings; however, the same correlation did not exist for the Step 2 CS data gathering score. Another study in 2013 found that the Step 2 CS communication and interpersonal skill scores have a modest relationship to communication skills in first-year internal medicine residents.

The Politics

The USMLE Step 1, 2 and 3 are sponsored by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the NBME. All states require successful completion of the USMLE, although, states vary in the number of attempts that are allowed. As Dr. Katsufrakis said,

“The impetus for the exam comes from states’ licensing boards. I think that’s another flaw in the logic underlying the petition: that the NBME is unilaterally and arbitrarily requiring students to take this. But actually it’s the states’ licensing boards that require students to take the examination.”

Given most schools have some version of the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), perhaps the best way to get rid of Step 2 CS is to petition the state medical licensing board to allow successful graduation from an accredited medical school be sufficient for licensure.

The Question

Where does this leave us?

Is the few thousand dollars you spend on Step 2 CS a drop in the bucket considering the average medical student debt is over $160,000? Or, is the bigger issue that another, possibly arbitrary hoop, is left standing in the way of you achieving your dream?

To date over 13,000 medical students have signed the #endstep2cs petition, which went live on February 26, 2016.

Image credit: photo credit from #endstep2cs campaign