When you walk into your favorite fast-food restaurant, a simple decision between a burger or sandwich quickly turns into an algorithm with different variables — price, calories and the like — competing for your attention. Maybe you decide to enjoy the higher-calorie burger but pass on the side of curly fries. Or perhaps a bout of indecisiveness prompts you to leave for the sushi bar next door. Can the mental gymnastics that individuals use to please their savory taste buds be replicated in health care, where patients can browse a menu of health care services before deciding which hospital to visit?

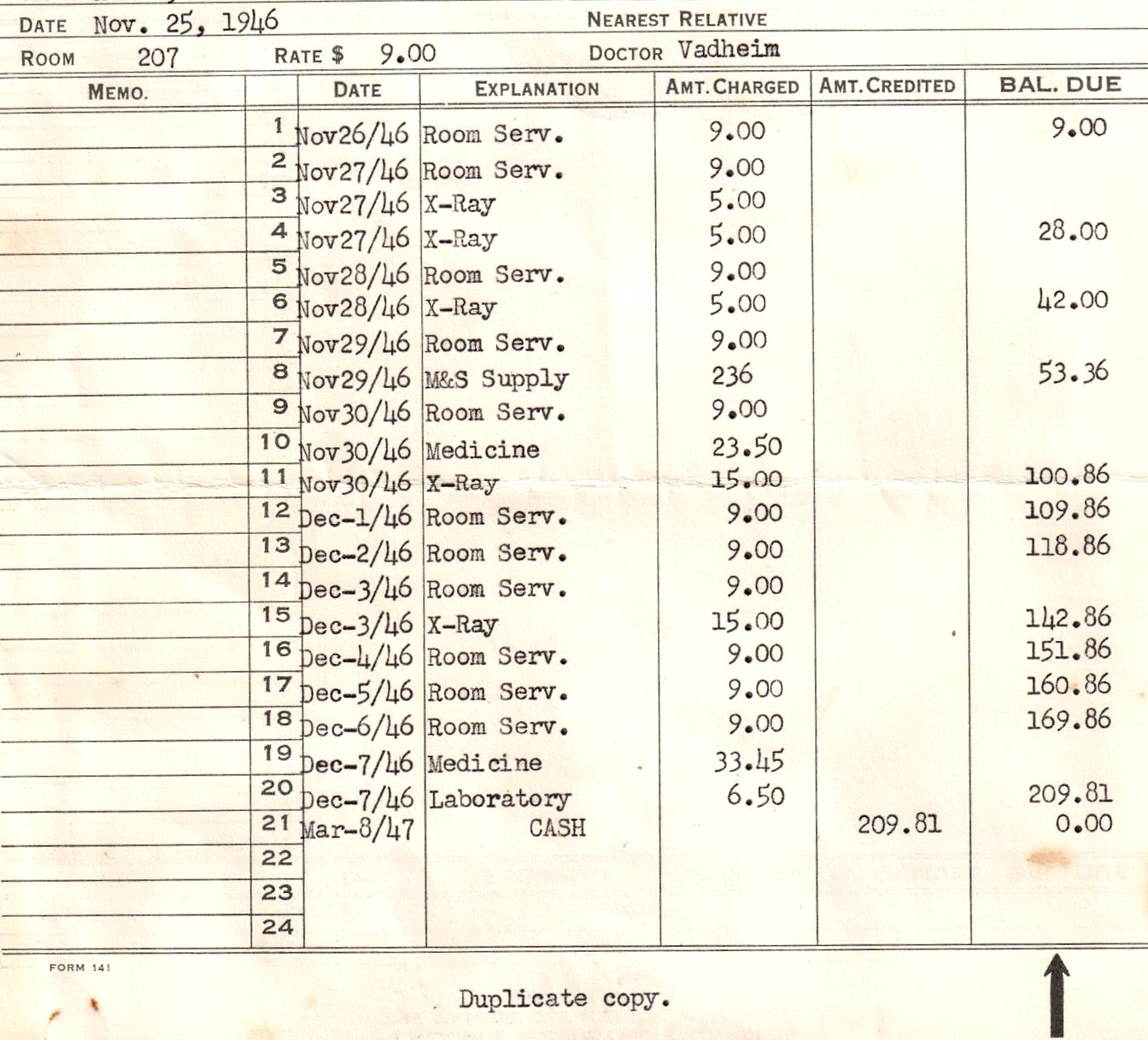

A hospital charge description master (or chargemaster for short) lists the prices of procedures, products and services that are factored into the patient’s final hospital bill. It is most commonly a list of average charges for 25 common outpatient procedures and the estimated change in gross revenue due to price changes. Hospitals themselves determine chargemaster prices for their institutions, using them to track service volume, costs and revenue and even to negotiate reimbursement rates from private payers.

However, this is not the kind of menu you find yourself meticulously scanning when you get seated at a restaurant after a long day of work. Chargemasters have generally been held as proprietary information of the hospital that patients, family members and other stakeholders do not have access to, perhaps unless a patient comes to the hospital ready to pay for every scan, needle-stick and fluid bolus out-of-pocket. This will no longer be the case moving forward.

President Trump signed an executive order this past June that directs the Health and Human Services Department to develop a rule requiring hospitals to disclose online the prices that insurers and patients pay for common items and services. The rule also requires hospitals to reveal the amounts they are willing to accept in cash for an item or service. However, hospitals not complying only face a civil penalty of $300 a day, giving them latitude to effectively ignore the executive order. Trump’s executive order is formalized by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule, which applies to every hospital in the United States and is set to be effective on the 1st of January next year.

The Benefits

There is reason to believe that the executive order could improve healthcare. A recent Health Affairs study showed that the average hospital with over 50 beds had a charge-to-cost ratio of 4.32, meaning that hospitals charged $432 when the service cost was $100. An additional study found that hospitals on average charged over 20 times more than their own costs for CT scans and anesthesiology services. The real aim of publicizing chargemaster lists is based on the principle of transparency, enabling more outside scrutiny of pricing across competing facilities that can facilitate strategies in the private sector to lower overall costs of care.

Over half of Americans suffer from hardships related to the cost of care. Empowering everyday Americans with price information on hospital websites can put decision-making back in the hand of the patient. Patients will have the ability to search for the hospital or clinic most appropriate for them to visit for a follow-up, emergency or other lab study based on their financial situation. The hope is that in response to knowledge about price markups, major health organizations and corporations will feel pressured to lower the price of care. There is evidence that this logical sequence can play out in real life: among general acute care hospitals in North Carolina, the percentage of hospitals providing access to chargemasters went from 0 to 72% from 2017 to 2019 in response to state policies. During the same period, the average price per item in the state along with price variability for a sample of hospital services decreased.

Potential Challenges

At the same time, this recent order has drawn the ire of those who do not believe the policy will actually work. While the chargemaster will make the list price of a hospital service available, that price is typically not what patients see in the final bill. Similar to how the sticker price on a car is just an imaginary ceiling, what the patient pays is based on the outcomes of insurance company negotiations with the hospital, whose interactions we will not see in the chargemasters, and the patient’s specific condition, financial status and insurance coverage.

In addition to the dimension of insurance coverage, it is unlikely patients will be able to pick and choose what hospital services and procedures to receive before being admitted. This contrasts markedly from services such as the restaurant industry, where one has flexibility to pick a type of cuisine or entree, cancel or change an order and finalize the bill before the food is even served. Emergency medical technicians will not hold up the ambulance by first confirming which nearby hospital takes your insurance for the likely condition you are facing. Estimates for complex care and emergency services are uncertain and can even change course as the final diagnosis is confirmed or as new issues emerge.

Critics are concerned that displaying these prices may lead to individuals willing to risk their lives just so they can be transported to a hospital of their choice, which might not even provide the price that they found online. This goes without mentioning that less financially privileged patients generally retain less freedom to choose where they receive care due to restrictive insurance policies or lack of insurance, less time off from work or even transportation limitations.

Additional criticism of the executive order vocalizes that the real issue behind hospital pricing will remain looming. While requiring hospitals to go public with their prices is a commendable first step, critics wonder what exact steps will then be taken to address unbelievable markups on services, procedures and products that hospitals enforce.

Implementing the Executive Order

As the merits and challenges of chargemasters linger on, another area of discussion is if hospitals will follow suit. An estimated cost of hospitals to release these spreadsheets of drugs, supplies and facility or physician fees is up to $39.4 million. CMS administrator Seema Verma states that the agency has no means of enforcing the Trump Administration’s price transparency order. If certain hospitals hide the information deep on their website or outright refuse to provide it, it may be difficult for anyone to enforce and take legal action against said major hospital and healthcare companies.

While the order has been announced and a deadline set, it will be fascinating to see how many and which kinds of hospitals comply. Some hospitals are already making access to the chargemaster easily accessible from their internet homepage. Many other hospitals require some digging on their webpage to come across the list, likely longer than the amount of time the typical internet user is willing to spend to find this information. PriceChecker, an online out-of-pocket cost calculator launched by St. Luke’s University Health Network, a 10-hospital system with 300 outpatient clinics in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, only received an average of 2,500 monthly visits in 2018. Another health network stated that it will not post chargemaster information until it can “ensure accuracy and clarity,” which reads with a level of irony given that it is the one billing the patients.

What the Future Holds

The current government administration’s vision is to have consumers armed with information to ensure reasonable prices before visiting a hospital. However, hospitals are pushing back: numerous hospital groups, including the American Hospital Association (AHA), filed a lawsuit claiming that the executive order is in violation of the First Amendment “by provoking compelled speech” and moves beyond transparency measures outlined in the Affordable Care Act. The federal judge ruled against the lawsuit, and the AHA was also unsuccessful in having this decision reconsidered in a federal appeals court in July.

In conclusion, the recent executive order by the Trump administration is one step in the direction of financial transparency in healthcare. While there are potential benefits to uploading chargemasters to hospital websites, it is unclear if doing so will ultimately prove useful in advancing informed decision-making and more importantly preventing surprise medical bills and price inflation. The insurance industry has already made its stance clear that the price transparency rule will be too expensive to enforce and too complicated for patients to garner value from. As hospitals prepare to comply (or not) with the January 1st deadline, only time will tell if patients will find chargemasters as inviting as the menu of your favorite fast-food establishment.

Image credit: 1946 Hospital Bill (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by HA! Designs