It was 5 p.m. on a Thursday and I had just finished my first preceptorship session with my fourth-year medical student preceptor. That afternoon was one of many firsts, as it was also the first time I conducted a patient interview. My first-ever patient was a middle-aged woman in the emergency room talking to me through Zoom. I remember introducing myself nervously, stuttering on the few syllables that make up my name, and then asking what brought her to the hospital. She responded that she had COPD and was in a great deal of distress. When I asked her to further describe how she felt, she responded that she felt like she couldn’t breathe. She started describing how hard it was to go up the stairs or go to her daughter’s house.

Even through a Zoom screen, I felt honored by the amount of trust that she had placed in me and I really wanted to help her despite having limited knowledge as a student in my first month of medical school. Afterwards I went home, sat at my desk, opened up a syllabus, and tried to study while still replaying the interview in my mind. I thought about potential words I could have said, words that maybe could’ve helped her or given her hope, and I wondered if she was feeling any better. Opening up to a blank page in my notebook, I started writing a poem about meeting my first patient. I wrote down anything that came to mind, including everything from the patient’s narrative to what the weather was like on my way back home. After an hour of expressing my thoughts on paper, I felt a lot more relaxed and happy, as if my mind was recharged. I began to wonder about how art, whether creating it or experiencing it, affects the brain and confers these positive mental health outcomes.

One form of art that has been well studied in neuroscience is music, an art form that has been an important part of humanity. Much is left to be discovered about the neural basis for our complex emotional responses to music. However, we do know that music can modulate the activity of the brain’s mesolimbic system, which is important for reward processing. Menon and Levitin conducted a study with 13 right-handed non-musicians and hypothesized that the nucleus accumbens (NAc), as well as the hypothalamus, would be activated when subjects listened to classical music. The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that controls autonomic response to emotional stimuli. Their hypothesis was proven, as “significant activation was observed in several subcortical regions including the NAc, VTA, and the hypothalamus.” This study also showed the activation of the NAc despite no explicit reward being present, such as a monetary reward. Because the hypothalamus is activated in passive listening, the pleasurable, reward-inducing experience of listening to music is often accompanied by changes in heart rate and respiration, reported by listeners as a “thrill” or a “chill.” In this way, simply listening to your favorite song on the bus involves a complex neurological process that bridges physiology and art.

The visual arts have also been studied in relation to neuroscience and human physiology. Neuroscientist Semir Zeki wrote that artists are, in a sense, neuroscientists who “explor[e] the potentials and capacities of the brain.” Neuroscientists have attempted to explain how artists are able to create pieces that are so “aesthetic” and visually appealing. For example, V.S. Ramachandran has come up with an explanation for the appeal behind cubism, explaining “why simultaneous views of an object from multiple vantage points is ‘more pleasing’ to the viewer.” The physiological basis that Ramachandran proposes is rooted in the fusiform gyrus, a region of the brain involved in face and object recognition. He claims that certain cells in this region can only respond to particular views of a face, while others called “master face cells” can respond to all views of a face. Many times portraits show only one view of a face, but cubist artwork typically shows multiple views of a face. This can “cause multiple ‘single view’ cells to fire at once, thus hyperactivating the ‘master face cells’ and exciting the limbic system accordingly.” The way cubist painters are able to manipulate different viewpoints can then be seen as a neurological treat of sorts, one that leads to activation of the limbic system and a subsequent behavioral and emotional response. Harvard psychologist Patrick Cavanagh also claims that “our visual brain uses a simpler, reduced physics to understand the world,” which visual art augments by allowing the incorporation of subtle aspects of images that typically go ignored in daily life.

Although science and art are generally considered as discrete entities in our culture, there is actually significant interplay between the two. Artists are able to create works that increase the activation of regions in our brain that are involved in reward and emotion, allowing us to see things that we normally don’t see through shadows, colors, and reflections. It is incredible that our brains are able to be so responsive to artistic stimuli, and that all of these complex processes occur by simply listening to our favorite song or watching our favorite movie. Art also has the incredible ability to heal and soothe the mind, and medical students can use art to take care of their mental health while processing emotions surrounding patient encounters. By creating art, medical students develop skills in perspective-taking while also gaining a “deeper appreciation of the experience of illness.” In this way, creating and consuming art can have a beneficial impact on the practice of medicine.

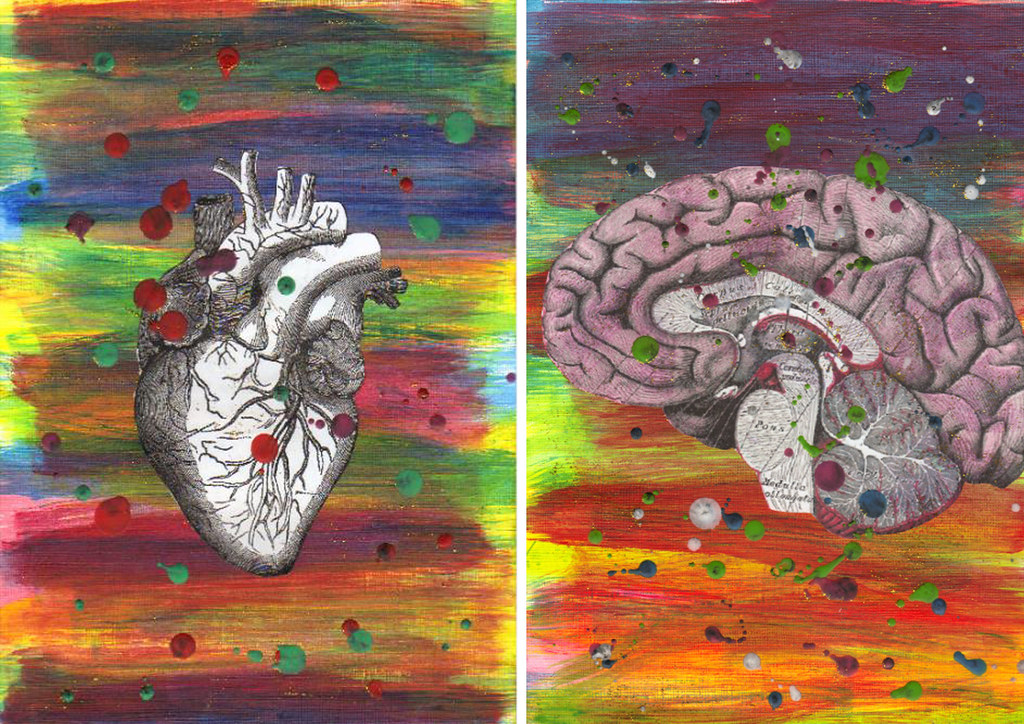

Image credit: Organs (CC BY 2.0) by ohhhbetty