In 2006, India Arie released a self-empowering song called “I am not my hair.” For women of color, this song became an anthem that empowered and permitted a level of self-identity that challenged societal norms. This song ignited the rebirth of a social movement for black women to embrace their natural hair. Different from previous natural hair movements of the 1960s-1970s, this renaissance involved professional women growing comfortable embracing their unadulterated hair in the workplace.

Image credit: India Arie by p-duke licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

In 2018, Nielsen reported that black consumers spend nine times more in hair and beauty than non-blacks do. Many would believe this disproportionate representation in the market is due to the black community focusing on vanity or appearance. On the contrary, from personal experience, this over-representation in the market is due to one’s hairstyle serving as a proxy to their beliefs, actions and opinions. Some professional women fear this can be detrimental towards their career and workplace success which causes them to conceal their curls.

The infamous July 2008 issue cover of The New Yorker reinforced this fear when First Lady Michelle Obama depicted with an Afrocentric hairstyle was used as a political tool to promote an aggressive and militant image of the first couple, an image that was opposite to one the First Lady wanted to present to the American people. With hair discrimination in the workplace becoming more common place concern for women, there is some hope for change on the horizon. The New York Times’ revolutionary article on New York City’s ban on discrimination against natural hairstyles in the workplace has proven this modern day movement’s strides to change the world around us have been successful. However, this movement has not yet advanced into the world of medicine.

The infamous July 2008 issue cover of The New Yorker reinforced this fear when First Lady Michelle Obama depicted with an Afrocentric hairstyle was used as a political tool to promote an aggressive and militant image of the first couple, an image that was opposite to one the First Lady wanted to present to the American people. With hair discrimination in the workplace becoming more common place concern for women, there is some hope for change on the horizon. The New York Times’ revolutionary article on New York City’s ban on discrimination against natural hairstyles in the workplace has proven this modern day movement’s strides to change the world around us have been successful. However, this movement has not yet advanced into the world of medicine.

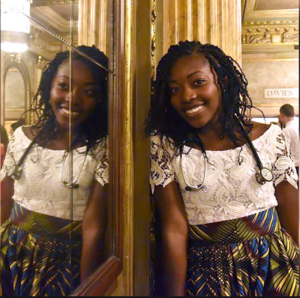

As a black female medical student and mentor for pre-medical students, the first question I am often asked by interviewing minority women is: “How should I wear my hair on interview day?” For those who are non-minority, the answer would appear simply to be simple: neat, clean, and professional. For women of color, however, the question prompts a much deeper discussion. This question is implicitly asking: “If I wear my natural hair, will I be denied acceptance?” Additionally it asks: ”What is the safe hairstyle that will not make me appear threatening or too ethnic?” As a person who will undergo the medical interview process for residency and beyond, I always feel unable to provide a comforting answer as I still question myself if there is a “safe” hairstyle to wear.

During my pre-clinical years, if I was not drowning from the amount of medical knowledge thrown my way, the little spare time I had was focused on making sure my hair was always professional. Since our exams occur every 6-8 weeks, I would have to make sure the hairstyle I chose could endure that stretch of time. Hair care for women of color can be tedious, time-consuming and at times annoying; as it takes time to make sure, it is always neat and presentable. Therefore, not changing hairstyles for extended periods in medical school is common. At the end of the eight weeks, instead of spending time outside of the classroom with classmates at a post-exam celebration, it was spent at home, figuring out the next best hairstyle to take on that will last for the next set of exams. To many, this would seem excessive or unnecessary, but for many professional women of color who have experienced microaggressions related to hairstyles, it is necessary to avoid future microaggressions.

“This is more than hair.”

–Dr. Magdala Chery

Dr. Magdala Chery, DO, internist

My outlook shifted recently after attending a session on Natural Hair in Medicine at the Annual Medical Education Conference (AMEC aka Medical Wakanda) hosted by the Student National Medical Association (SNMA). The session — standing room only — comprised a panel of attending physicians and residents who discussed their personal journeys and the importance of natural hair in medicine. When Dr. Magdala Chery mentioned “This is more than hair,” I was astonished as I felt a deeper connection to this statement. I would later realize she was referring to my professional identity within medicine and reliability with patients.

A September 2018 Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) article focused on minority resident experiences in the workplace while developing their professional identities. The article states “aspects of their cultural identity were ignored at work. Residents perceived pressure to assimilate into the social culture specific to their institution while noting that their residency programs made little effort to integrate aspects of minority culture into the educational environment.” The limited inclusion of minority cultures into the educational environment can make minority residents uncomfortable in their work environment; however, from a healthcare standpoint, it limits their ability to connect with a diverse patient population.

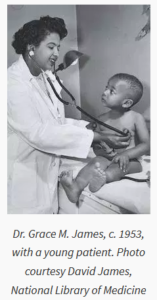

Several panelists shared how aspects of their cultural identity helped them develop better physician-patient relationships with minority patients. Dr. Italo Brown points out, “I’m the guy that looks like that patient’s grandson. When I walk into the room and they see me, they are reminded of their family and I’m able to connect a little bit more, which allow me to encourage patients to take their medications or able to advise them to take a diagnosis more seriously. They will listen because of the level of relatability.” Dr. Brown’s statement is proven true, from a recent California study Does Diversity Matter for Health? which found patients “brought up more issues and were more likely to seek advice from black doctors, as reflected in the doctor’s notes.” By having a diverse workforce, we can make a bigger impact on the health of minority patients.

Our communities are more diverse, for that reason, it is important for medical professionals to find ways to connect, relate and identify with our diverse patient population to deliver needed medical care. Although medical schools across the country have taken bold strides to increase safe spaces for underrepresented minority medical students, not explicitly condemning natural hair discrimination in medicine and medical education causes medical students, residents and practicing physicians to feel vulnerable to discrimination in the classroom and workplace. I am hoping medicine takes note of New York City’s pioneering ban on natural hair discrimination. This new ban will help make work environments safer for many minority professionals.

Our communities are more diverse, for that reason, it is important for medical professionals to find ways to connect, relate and identify with our diverse patient population to deliver needed medical care. Although medical schools across the country have taken bold strides to increase safe spaces for underrepresented minority medical students, not explicitly condemning natural hair discrimination in medicine and medical education causes medical students, residents and practicing physicians to feel vulnerable to discrimination in the classroom and workplace. I am hoping medicine takes note of New York City’s pioneering ban on natural hair discrimination. This new ban will help make work environments safer for many minority professionals.

Featured image credit: Business people in a meeting by Rawpixel Ltd licensed under CC BY 2.0.