Recently…

Recently, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, one of Harvard Medical School’s teaching hospitals, made the decision to disperse portraits of past white male luminaries to help foster a more diverse environment. To my excitement, this came a few weeks after, but likely unrelated to, my Letter to the Editor, published in the Journal of Academic Medicine, drawing a contrast between the portraits on the wall at my alma mater Howard University, and my medical school, Yale School of Medicine, and describing the implications for the overall climate and my experience as a Black male medical student.

Contrast Between Institutions

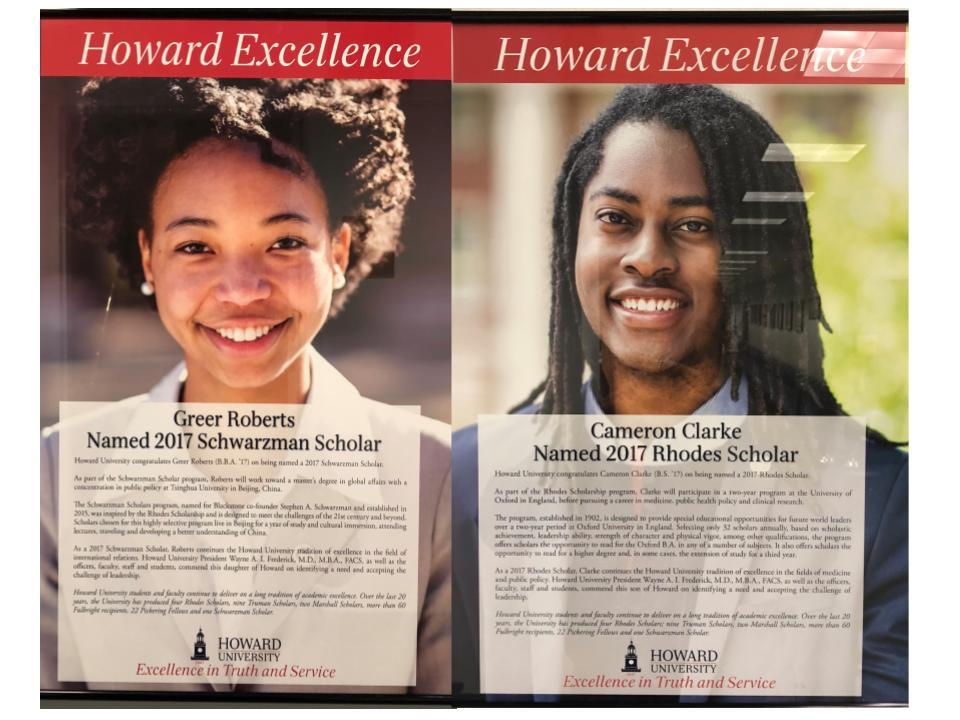

At Howard University, I saw recent Fulbright Fellows and Rhodes Scholars on the walls. I was inspired by their achievements: I could see myself in those students. Not only were they Black, they were also close to me in age and stage. That spatial and temporal proximity made it such that I could relate to their experiences and aspire to their academic prowess. I even befriended some of those students.

At Yale, the walls tell a different story. The central space of the library is a rotunda lined by black-and-white pictures of men who graduated from the Yale School of Medicine and prominent Connecticut physicians. All eight pictures depict White men donning dark robes and silk cravats that exude the aura of British aristocracy. They studied medicine in the late 1700s and early 1800s, an era when Black people and women of all kinds were not allowed into medical school. As a member of the Harry Potter generation, I wonder, “If these men could speak from their portraits, what would they say to me?” After all, they studied medicine at a time when anatomy was taught almost exclusively on bodies like mine: those of Black people.

Upstairs, where the Dean’s suite and several research laboratories are housed, the pictures on the wall seem more recent. They are pictures of several previous Deans as well as prominent alumni of the medical school. But, again, they are all White men. There is only one portrait that stands out, a much smaller and almost unnoticeable picture, one of a different quality. It’s the picture of the first female faculty member of the medical school. This picture is a sign of progress, but it isn’t enough.

As institutions of higher learning are becoming increasingly diverse, the portraiture that hangs in these institutions should reflect the bodies that inhabit their halls. Here, I argue that recency is particularly needed in academic medicine, and will propose some strategies for achieving it in our academic medical centers.

Medical Schools and Portraiture

Medical schools have canonized prominent physicians in the forms of oil paintings, portraits, building, suites and firm names. Given the history of the field, those physicians are overwhelmingly male and White. The landscape and physical environment recognizing almost exclusively people who are White and male sends a message to its dwellers and observers about who is important and gets to be celebrated. Allocation of space is often tied to the interest of different groups and individuals, often with large financial contributions to the institution. The individuals highlighted are often donors or those with strong ties to the institutions.

This has an effect on the experience of those who inhabit our institutions. It is not uncommon especially for underrepresented minority students to feel unwelcome at their institutions of training. For me, the pictures on the wall have only, in some way, reinforced that notion: I personally feel uninspired by the faces I constantly see on my way to the library, not just because they are White men from a previous, less kind era to people who looked like me, but also because they became physicians in such a distant and different time that I likely could not relate to their experiences. I’d argue that even my White male colleagues would have a hard time identifying with the likes of Harvey Cushing, for example, given how much medicine has changed both in practice and the way it is taught since his time. Could you imagine, for example, using X-rays as a diagnostic tool in deciding whether to operate on brain tumors given today’s standards of practice?

In medical school, we are taught the importance of being egalitarian, treating every patient we encounter the same way. We are also taught to value the perspective of colleagues from different backgrounds and professions through institutionalized manners that emphasize team work and inter-professional learning experiences. What we see every day, however, is contradictory to the egalitarian values we stand for: White men seem to be the only kind of individual we celebrate and canonize through our landscape.

Centuries after its founding, the medical school whose halls I navigate has changed significantly for the better, but there certainly is more work to be done. With ongoing efforts from student-activists, we have more recently created a committee for diversity, inclusion and social justice, which has led to the hiring of a Deputy Dean for Diversity, overseeing faculty and trainee/student diversity matters. These actions taken by the Dean and several department chairs suggest that diversity and inclusion matter more than it ever has at our institution. Individual departments are creating task forces to sustain these efforts and retention of minority faculty has become an important effort across the university.

Portraiture and Diversity Efforts

As this current of diversity and inclusion sweep medical schools, the focus has been on diversifying the numbers in terms of who inhabits the wards and the classrooms. But what is on the walls has not changed. We colloquially say that a picture is worth a thousand words, so how much do the countless pictures that adorn the walls of our hallways, libraries, meeting rooms say to their increasingly diverse inhabitants? What about who we decide to name spaces after? There certainly is value in recognizing pioneers and ancient aspects of the medical field as it reminds us how far we have come. However, the pictures on the walls of our academic medical centers should also serve as relatable inspiration for trainees through temporal proximity and reflect the diversity present among the faculty and student bodies.

Prioritizing Recency

Prioritizing recency in portraiture and changing space allocation policies can help address this. Last fall, I returned to D.C. for a cherished tradition: Howard University’s Homecoming. I walked the halls of my favorite buildings, and the pictures on the walls have changed. There are new Fulbright fellows and Peace Corps volunteers, to name a few. These students came to Howard after my time, and I felt a sense of pride seeing students from generations younger than mine being celebrated. Imagine if in faculty suites, resident lounges and study spaces for medical students, medical schools created an atmosphere where the adornments on the walls reflected the institutions’ current inhabitants and created in them a sense of inspiration because of such temporal proximity. It would be fair, meaningful and inclusive. This would require that we let go of the notion that permanence is important in landscape installations. We should become comfortable with the notion of rotating and evolving portraits. Older portraits could, for example, be stored in archive-like galleries dedicated to telling the history of the institution.

Portraits of recent prestigious scholarship awardees (2017 Schwartzman Scholar, 2017 Rhodes Scholar)

Fostering a Sense of Inclusiveness

In addition to rotating portraits with time, the policies that drive space allocation in our institutions should be preemptively inclusive. One can imagine a space where recency is applied but inclusion is not. Legal and social geography scholars advocate for landscape fairness, suggesting that universities apply more inclusiveness towards more responsible landscape policies. For example, in selecting a series of faculty to be recognized in a hallway, it should be important to take into consideration sex differences in attainment of independent funding, or factors that lead to certain groups being underrepresented in the medical field. This would ensure that we don’t inadvertently end up celebrating mostly individuals from a specific background or with a specific interest. In addition, institutions can expand from the current trend where mostly donors get space allocated. We can also include others who contribute to the legacy in different ways, including but not limited to academic prowess and leadership. This would make the spaces more welcoming to individuals visiting the medical school, considering it for undergraduate, graduate medical education, or faculty positions. It could also contribute to increasing minorities’ sense of belonging and ownership of the spaces they occupy.

From left to right: pictures of various fraternity and sorority members on Howard University’s Campus, picture of jovial graduating pharmacy student, and picture of Student Leaders commemorating the March on Washington

Success Stories

There are several successful precedents for the use of portraits in diversity efforts in higher education. For example, M.I.T. ran a campaign targeting first-generation college students by using the images and stories of first-generation faculty in admissions publications. They created a poster campaign using faculty with personal and family histories of mental illness to help facilitate discussions about mental health on campus and encourage good mental health practices, while demonstrating the possibility of mental illness coexisting with achievement and excellence.

Portraiture Weaponized

Conversely, the perceivably benign intention of landscape design has led to student and staff discomfort with their learning and work environment. Such was the case at Yale University, where Corey Menafee broke a stained glass window that depicted slaves carrying balls of cotton because of the burden of memorialized reminders of White supremacy in Calhoun College. Students at Yale protested for the renaming of Calhoun College for generations, and the University finally made the change. At times, the landscape has even been weaponized to inflict violence upon students and other dwellers of universities. Two years ago at Harvard Law School, students woke up to a statement of hatred: The portraits of the few Black tenured faculty at the law school were marked by black tape, while the overwhelming majority of portraits, those of White men, were left untouched.

At the time, my friend Michele wrote:

“The first time that I walked down those hallway, I was painfully aware of the White men that take up most of the space on the walls, but also proud to see Black professors hanging right beside them. The portraits make me feel a strange tension of pain yet promise.”

In Summary

The sense of belonging, inspiration and pride I have felt at Howard through seeing students ahead of me and students after me celebrated for their achievements is something I wish for myself and my colleagues as we navigate medical school. As noted above, a sense of diversity in the landscape, even if comparatively modest, can have a positive impact on its inhabitants. As medical schools become more diverse and commit to efforts of diversity and inclusion, they should not overlook the importance of the landscape inhabited by their increasingly diverse diverse student, faculty and resident bodies and the ways in which said landscape impacts each individual’s sense of belonging and experience at any given institution, but also silently contributes to shaping their attitudes towards colleagues and patients from various backgrounds.

Attending Howard University gave Max a foundation for and continues to inform how he approaches issues related to injustice. Now in medical school, he has made it one of his focal interests to learn about and contribute to progress towards health equity, nationally and globally. Through this column, he will share stories on his experience as a Black man in medicine, and insights on topics of race, class, health equity, and medical education.