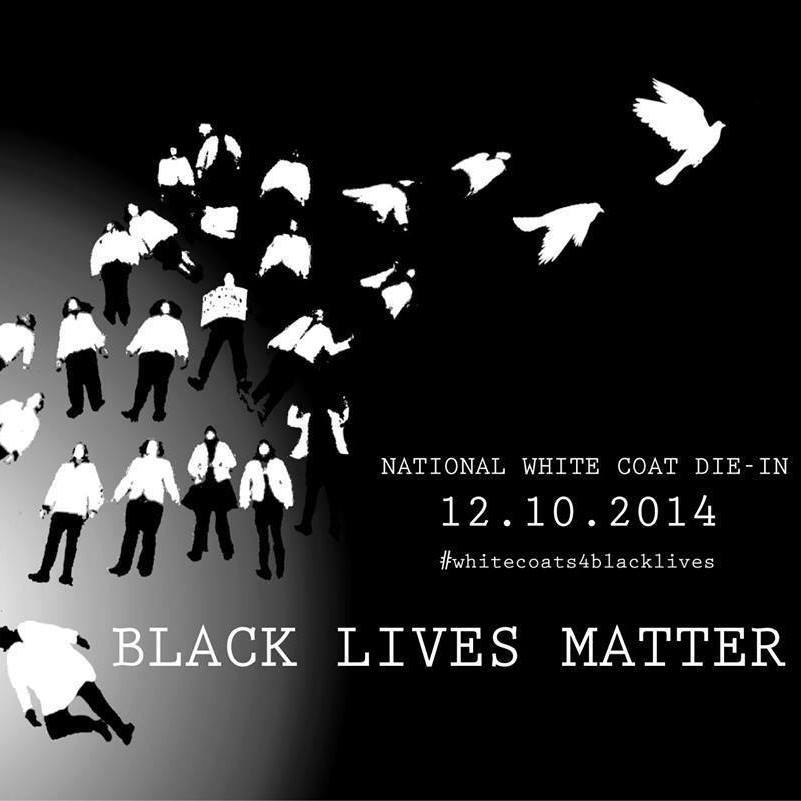

This afternoon, medical students across the country, from Providence to San Francisco, will lay down on sidewalks and atrium floors in their white coats to express solidarity with ongoing victims of racial violence. As aspiring health care professionals, we don our white coats for these “die-ins” to express our commitment to the idea that racial injustice can and should be framed as a public health issue demanding our attention and efforts.

We hope many aspiring and current health care professionals will attend these events and demonstrate their allyship on these issues. These “die-ins,” however small in their scope of affecting significant change, are meant to demonstrate a resistance to the status quo. Because silence on this matter seems to imply tacit agreement, we act to support resistance and opposition to the recent decisions not to indict — decisions which effectively endorse anti-black violence. Those who critique this act as a lazy form of activism or useless gesture may be valid in their opinions. This demonstration, however, seeks both to create engagement in our class and to send a message of solidarity to our communities, which can be valuable in its statement of validation — an incredibly powerful force in this world.

This demonstration is also a time for us to reflect. First, we should be careful to examine the complicated politics of our involvement by inspecting our motivations and intent. Second, we must ask ourselves how we can advocate in meaningful ways that do not reify existing power dynamics that allow such injustices to take place. In fact, we must keep in mind that we cannot advocate on behalf of others without first consulting them on their needs. These “die-ins” cannot be seen as acts of formal protest, because in their organization and execution, they do not include the involvement of broader local communities of color.

To be more clear, participation merits understanding that our white coats may help garner media attention not as easily generated by the people who are most directly affected by these instances of racial violence. This is, of course, not to say that these matters do not impact people within our medical school communities, but to remind ourselves that we do occupy a position of privilege as medical students. (There is of course a reality that, even with the privilege of our education, the black students among us are still oppressed by dominant anti-black structures.)

It is necessary for us to acknowledge our relative power and that our white coats grant us additional clout taken away from people like Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Deshawnda “Tata” Sanchez, is important. The white coat is powerful, and while we utilize it as a platform to clearly transmit our intent, we should also recognize how it may grant us attention that should be given to others. Thus, we need to be aware of where and how we take space in this movement. To be good advocates, we must ensure the people to whom we are committed to serving dictate the change that is needed. One aspect of success can be measured by our ability to return the microphone back to the communities of color that we serve. Ultimately, the intent of these demonstrations is to empower those most affected and step back to allow their voices to be heard.

Let us reflect on why we are participating in these events. Rather than showing up, snapping a picture, and failing to continue involving ourselves with these issues, we should treat these events as stepping stones for the commencement of further engagement. These “die-Ins” mean to demonstrate that issues of race and violence are important to public health and the well-being of the people we intend to care for. This requires continued effort, and cannot be demonstrated in one day. We urge those involved to continue to think about these issues after they get up off the floor: Remain critical of institutional bias, engage in conversation, direct attention to underserved communities, and actively consider these issues in practice as aspiring physicians.

In lectures of patient advocacy, we are frequently told, “When doctors talk, people listen.” It is important that we all think carefully about what we are trying to say. Our statement should bring visibility to the broader anti-racist struggle, and highlight the injustices that exist today. These “die-in” events will be much more meaningful if people, participants and observers alike, depart with a stronger sense of empathy, information and commitment to these issues.

For further reading or inquiry:

Decker, Scott H., et al. Criminal Stigma, Race, Gender and Employment: An Expanded Assessment of the Consequences of Imprisonment for Employment. Final Report to the National Institute of Justice. 2014.

Fang, Jing, Shantha Madhavan, and Michael H. Alderman. “The association between birthplace and mortality from cardiovascular causes among black and white residents of New York City.” New England Journal of Medicine 335.21 (1996): 1545-1551.

NAACP. “Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.” 2014.

Satcher, David, et al. “What if we were equal? A comparison of the black-white mortality gap in 1960 and 2000.” Health Affairs 24.2 (2005): 459-464.

Shapiro, Thomas, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro. “The roots of the widening racial wealth gap: Explaining the black-white economic divide.” Institute on Assets and Social Policy (2013).

Williams, David R. “Race, socioeconomic status, and health the added effects of racism and discrimination.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896.1 (1999): 173-188.