I thank my hands.

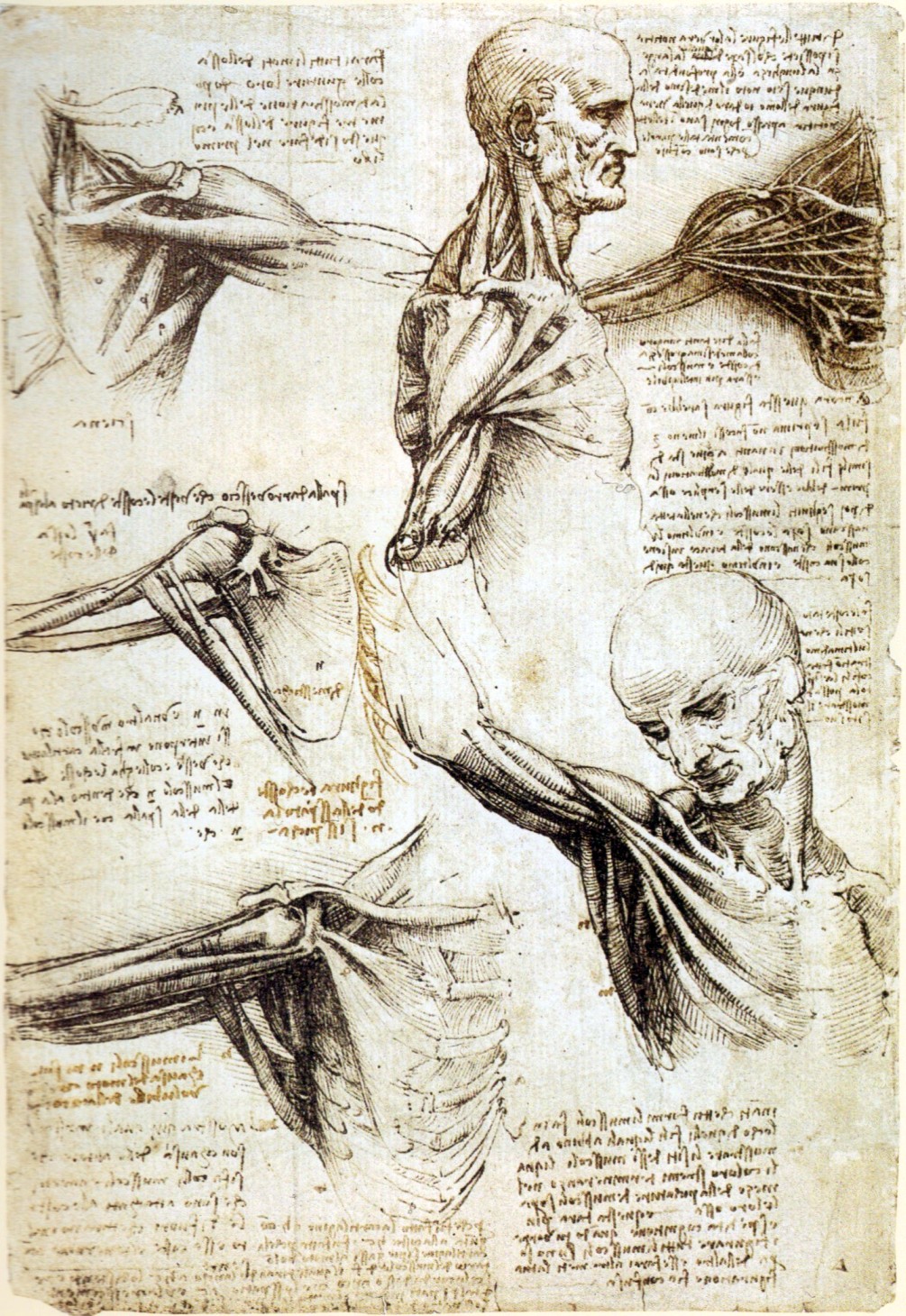

In the past six months, they have gripped countless coffee cups after nights with too little sleep — allowing me to sip liquid fuel so I can better concentrate. They have drawn pathways over and over again, helping me internalize everything from glycolysis to the courses of the cranial nerves. They have shaken while holding a scalpel for the first time hesitating before making a cut in fear of desecrating the body of a deceased human. They have progressively grown more confident learning how to be more precise and working through everything from the arteries of the abdomen to the tiny muscles of the eye. They have wiped my tears when I was utterly overwhelmed by the sheer intensity of medical school and the amount of information I was expected to learn.

I thank my voice.

In the past three months, I have learned how to palpate pulses, how to percuss the lungs, how to auscultate bruits and how to elicit reflexes. As I learned various physical exam maneuvers to test for signs of appendicitis and ACL injuries, I may have stumbled over finding the right words while explaining why I stroke the bottom of a patient’s foot with the tip of my reflex hammer testing for the plantar reflex. But my voice rang of confidence that my brain had not yet processed, and this allowed me to push through. Even if I messed up, as I did and still do many times, my voice did not waver even when my hands trembled. My voice also served as my catharsis allowing me to sing with strength after a difficult day even if my heart felt weak. As I sang the alto part of “Smile” in our school’s a capella group, my voice was joined by ten to fifteen others: Together, we all translated our emotions into song.

I thank my mind.

I left the anatomy lab at times having held or cut a vital organ of a person I did not know who lived a life I knew nothing about: I was expected to continue about my day. Constantly, I felt the cognitive dissonance between the emotional intensity of dissections and the mundaneness of chores like laundry and grocery shopping, yet I performed these tasks even if I had not understood how to resolve the gap. My mind helped me cope with experiences too overwhelming to process. Sometimes, I processed them through reflection and other times in my choice to re-watch The Office for humor and familiarity. When my instinct was to feel inadequate or that I was in the wrong place, my mind urged me to talk to friends and family and to remind myself of my worth.

I thank my eyes.

They allowed me to appreciate the beauty of the chordae tendineae, the sulci of the brain and the indentations of arteries on the back of the lungs. They let me observe what patients might not be willing to say aloud: the discomfort of hunched shoulders, the nervousness of trembling hands and the slight tapping of a foot in anticipation of difficult news. Blearily they opened each morning and stubbornly refused to let me sleep again knowing that I had things to learn and places to be.

If gross anatomy has taught me any topics, they are the sheer beauty and capability of the human body. My body is no exception, and for everything it does and will do for me in the future, I am grateful.

Image credit: public domain, obtained from The Athenaeum