“Shut up and dribble.”

A White female Fox News reporter aimed this “criticism” at LeBron James in 2018 — a criticism dripping in minstrelsy.

In 1830, Thomas Dartmouth Rice wore blackface and played a stage character named “Jim Crow,” an exaggerated cartoonish and racist stereotype of a Black man. America was so pleased by his performance that blackface minstrelsy — racialized song and dance — became common entertainment. Thus began the practice of ascribing value to blackness as entertainment and entertainment only.

Today, some of our most prominent entertainers are Black: Oprah Winfrey and Michael Jordan are the third and fourth wealthiest celebrities as of 2017. Blackface “entertainment” — as a derisive representation of Black people — has been condemned and erased; now, Black Entertainment Television provides a space for Black Americans to represent themselves. But the history of minstrelsy persists whenever we criticize Black celebrities for having an opinion about being Black in America.

In some cases, criticism is only the beginning. In 2017, Colin Kaepernick played his last season in the NFL after engaging in a season-long peaceful protest against police brutality by kneeling during the national anthem. After that, no team would sign him because he was controversial, and, therefore, bad for business.” In other words, the NFL conspired to keep him out of the league because his activism was interfering with their expectation that he stand up and play. What surprised me most about Kaepernick’s situation is that even successful athletes could be punished for caring.

And as an athlete myself, that left me thinking, what does that mean for me?

While playing college basketball, I avoided having an “opinion” about social justice because the power dynamic was apparent. I didn’t want to lose playing time, and I’m not proud of that. But after my coach laughed at the mehndi on my hands from a wedding, I got the sense that being different was trouble — and I wasn’t ready to get into “good trouble” yet. More than that, I loved basketball so much that I was afraid to lose it.

Now, I am a fourth-year medical student standing at the foot of a tall ladder. The hierarchy of medicine requires that I follow some unwritten rules in order to climb. Throughout my training, I have gotten the sense that one of those rules is: avoid trouble, good or bad. Of course, now, doctors are beginning to find their voices through movements like White Coats for Black Lives. But as a young trainee, I sometimes feel the sentiment directed at James in 2018: shut up and doctor.

I recently wrote a piece published on Doximity about how police brutality was robbing Black Americans the right to “a good death,” a concept that I learned about in my palliative care course. One comment from a physician reads, “ALL lives matter. Physicians should be above politics.” While the suggestion that doctors are “above” politics implies superiority, what it really does is silence our humanity. And physicians are kept quiet even at the national level by policies like the Dickey Amendment, which historically disallowed gun violence from being funded and studied as a public health issue. I find it especially mind-boggling that physicians today are groomed to be neutral when the history of medicine is bathed in strong, bigoted opinions.

Perhaps the best example is the work of a respected Louisiana physician, Dr. Samuel Cartwright, who was also a professor of “diseases of the Negro.” In 1851, he published a paper in The New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal that not only reported “evidence” on the physical inferiority of Black people but then also used said “evidence” to justify slavery. For example, he claimed that forced labor would “vitalize” the blood and correct the 20% lung “deficiency” of Black people. This is the basis of race-based spirometry today.

It’s almost as if the medical field, historically, has had more to say in support of bigotry, like racism, than against it. Doctors like Samuel Cartwright used science to “prove” the inferiority of Black people; in turn, science embraced racism through horribly unethical experiments like the Tuskegee Study where penicillin was intentionally withheld from Black men with syphilis. Other forms of bigotry, like ableism, have also been emboldened by medicine; for example, the field of eugenics permitted the sterilization of nearly 20,000 “feeble-minded” people — without consent — in California.

Today, the trainees who are targeted the most by discrimination are also the trainees with the most to lose by speaking up. And, understandably, they might fear losing everything like Kap, especially since we’ve all worked so hard to get here. As a result, medical students who are the minority often feel the moral distress of two extremely difficult tasks: doing the right thing and learning medicine. In a way, it sometimes feels easier to shut up and doctor.

But just as the comment directed at LeBron James is ludicrous, so is the suggestion that doctors doff their humanity when they don their white coat. Without doubt, the profession is unique in that, regardless of what we believe, we are expected to care for every patient equally and equitably. Thus, doctors are held to a higher standard — but that position decidedly does not put us above caring. Rather, we are defined by it.

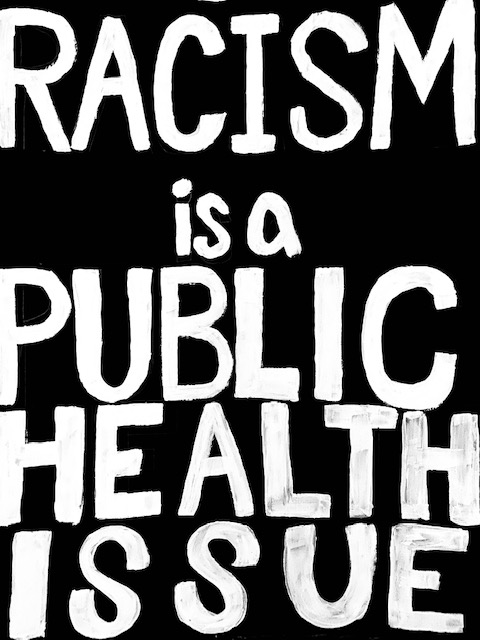

In fact, as guardians of public health, medicine is a means to an end rather than the end itself. It is our ethical duty to protect and serve our patients. And if caring is political, then I say: let’s get political. Because our profession ought to embolden us to advocate rather than quash us with myths about professionalism. In the last few months, the perfect storm of coronavirus, police brutality and climate change has made one thing clear: it is time for physicians to get into some good trouble.

Image credit: Image provided by the author.