By this the time of year, most first-year medical students have finished with anatomy. Anatomy: for most of us, this course is our first time seeing a deceased human being in an academic setting. And for some of us, the first cut we make on the first day of anatomy is the first cut we make on a person’s flesh. Sound scary?

By this the time of year, most first-year medical students have finished with anatomy. Anatomy: for most of us, this course is our first time seeing a deceased human being in an academic setting. And for some of us, the first cut we make on the first day of anatomy is the first cut we make on a person’s flesh. Sound scary?

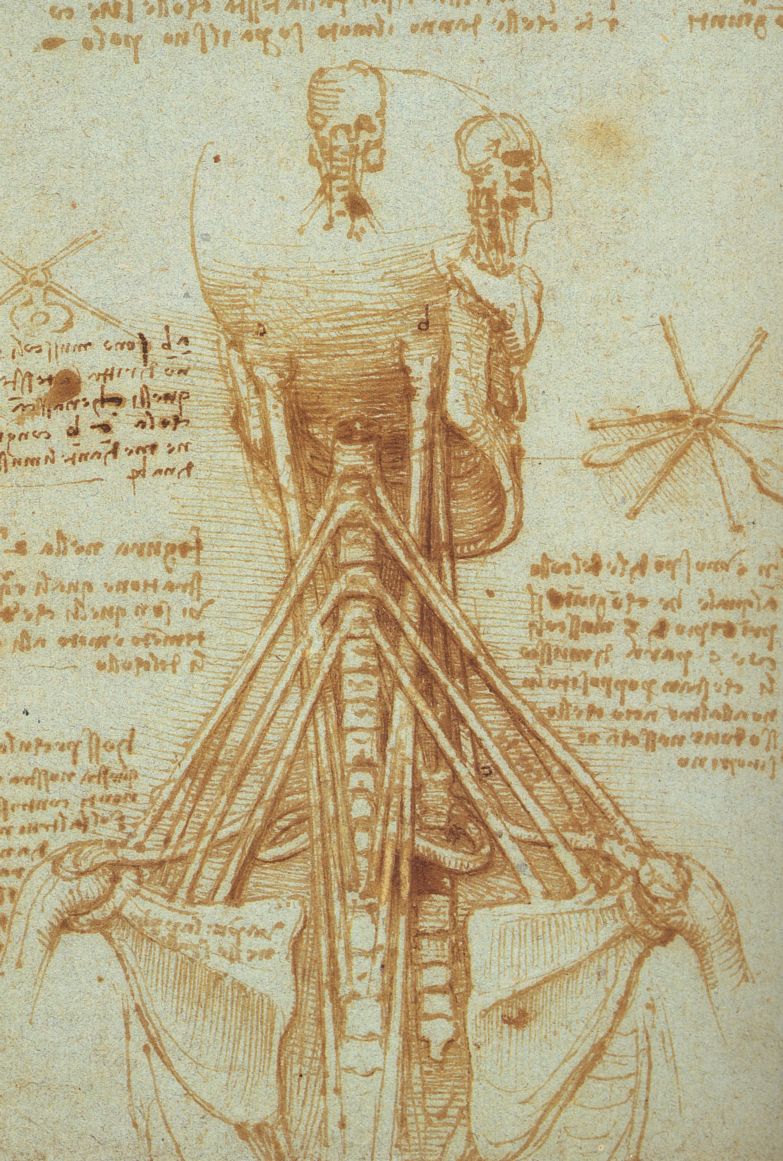

It did to me. But it also sounded amazing. To me, anatomy seemed like an amazing combination of art, history and medicine. I never cease to be amazed by Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of human and animal anatomy, Vesalius’s engravings and modern anatomical art (for example, Fernando Vicente’s Vanitas series or Juan Gatti’s anatomical prints. So you can imagine how eager I was on the first day of anatomy.

Follow me on the first day: I got up at 7 a.m., freshened up and got dressed, practically skipped to campus, changed into scrubs and sat in the lecture room. Our instructors gave a lecture on professionalism and discussed the implications of talking about body donors unprofessionally and in inappropriate settings. Then we had a lecture on the anatomy of the back — which was what we were going to start dissecting that day — before moving from the lecture room to the lab.

At first, we were silent. Twelve cadavers lie on twelve metal dissecting tables, face-down and covered in wet towels. Their limbs and heads were covered with towels and bagged to retain their moisture. They were a little intimidating — their stillness and their vaguely humanoid forms reminded me of mummies or sarcophagi. Silent, still and demanding of respect and reverence.

Leonardo da Vinci – Anatomy of the Neck – 1515

My classmates and I filed in, waiting in lines to pick up gloves, lab coats and eye shields. Then we each shuffled to our assigned tables. Mine was in the back of the lab. The harsh, chemical smell of the cadavers’ fixing fluids flooded our faces when we uncovered our cadaver’s back. I don’t remember who in my group made the first cut. But I remember my first cut: it was surprisingly easy. I might as well have been wielding a pen instead of a scalpel.

We spent a few hours revealing the back structures we had been assigned to dissect — the chatter in the lab grew louder and louder as we all grew more comfortable in our strange new surroundings. Our TAs and instructors encouraged those of us who handled our instruments gingerly and showed us how to bluntly dissect and create tension in the tissues to make them easier to cut. Then we were called back into the lecture room to review the day’s work. The day ended, we all went home to review again and look over the next day’s dissection.

We did this each day for seven weeks, and our list of assigned anatomical structures grew longer with each dissection day. The days blended together — my teammates and I spent more and more time in the anatomy lab and in study rooms, reviewing innervations and arterial supplies, quizzing each other from various review books. So if you ask me if anatomy was difficult — yes, it was! We studied so much, and I remember there were nights when I just couldn’t bring myself to open my books when I got home. I just couldn’t study anymore because I was physically exhausted. But … that’s not the only thing that’s tough about anatomy.

I still remember the face of my team’s cadaver. Her expression was soft and gentle. Her mouth was gently open as if she wanted to say something, but her brow was slightly furrowed, like she couldn’t remember what it was. Her expression puzzled me throughout the week when we uncovered her face to study the head and neck. I couldn’t help but liken the face of our cadaver to the faces of my elderly female relatives and friends. It was an unsettling association, but one that kept me careful.

I am so grateful for our cadavers’ sacrifices — they had given up a lot to become the teachers who stayed in the lab longest! But they didn’t just teach us anatomy. They taught us about mortality, about death — the force from which all physicians try to fend off, to protect patients. All without uttering a word.

Fernando Vicente – Escorzo – 2008

And so over the course of anatomy, my eagerness and enthusiasm transformed into respect and responsibility. These fueled my anatomy studying. I knew I was working really hard, but I didn’t want to waste our cadaver’s sacrifice. She had given her body in hopes of helping others by helping to train doctors. That meant I had a lot to live up to (and still do).

Fast forward to the day of our final exam: I got up extra early, ate a quick breakfast (I couldn’t stomach much) and went to the lecture room to do some last-minute cramming. When testing time started, I joined half the class and started the practical exam. We all rotated through the 12 tables, examining the structures that had been tagged with pins or tied with strings and trying to answer the second- and third-order questions that had been paired with them. I remember people craning their necks to follow certain tendons in the forearm, tapping their clipboards with their pens as they examined one of the pelvic arteries. When time was up, we swapped places with the other half of the class and started the computer portion of the exam. Thus commenced the frenzy of head-scratching and mouse-clicking. And finally… it was noon. It was over.

We breathed a sigh of relief and walked outside to breathe in the fresh autumn air. It was a beautiful blustery, sunny afternoon — perfectly matching our post-final dishevelment and joy. We’d survived the ancient medical student rite of passage. We all knew the human body as best as we could and were ready to take on the rest of medical school. Whether it was by luck or hard work, we’d made it.

As I walked home, eager to shower and wash the smell of formalin off of me for the last time (everyone smells badly during anatomy and there’s nothing that can be done about it), I realized that exactly one year earlier, I had had my medical school interview just around the corner from the anatomy lab. How different I had been one year ago, as a prospective medical student. How different I was now, having just spent seven weeks with my teammates at the side of my silent, but generous, anatomy teacher: our cadaver. I remembered saying goodbye to the cadaver the day before, and on my walk home I looked up and whispered my thanks.

As medical students, we shadow physicians to learn about the nature of medicine from them and their patients. In this column, Diem traces her own shadow, preserving and illustrating her experiences—in class, in the hospital, and in between—as a humble medical student.