The Anatomy of Healing

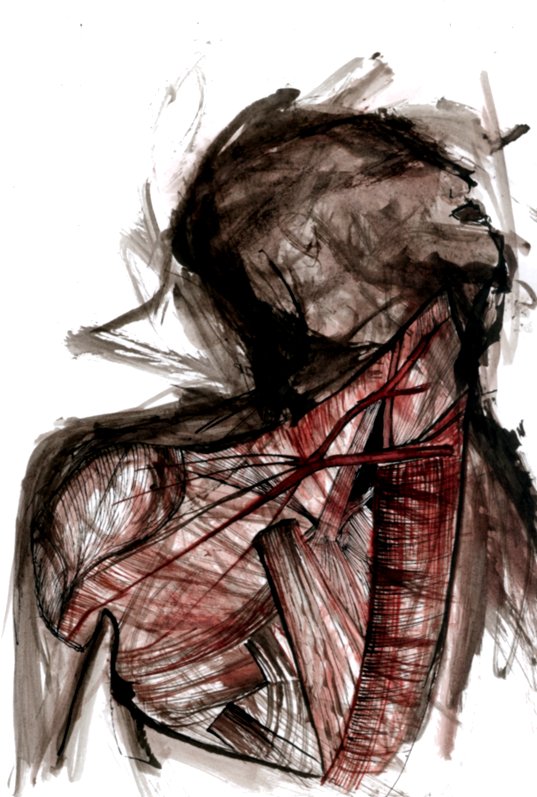

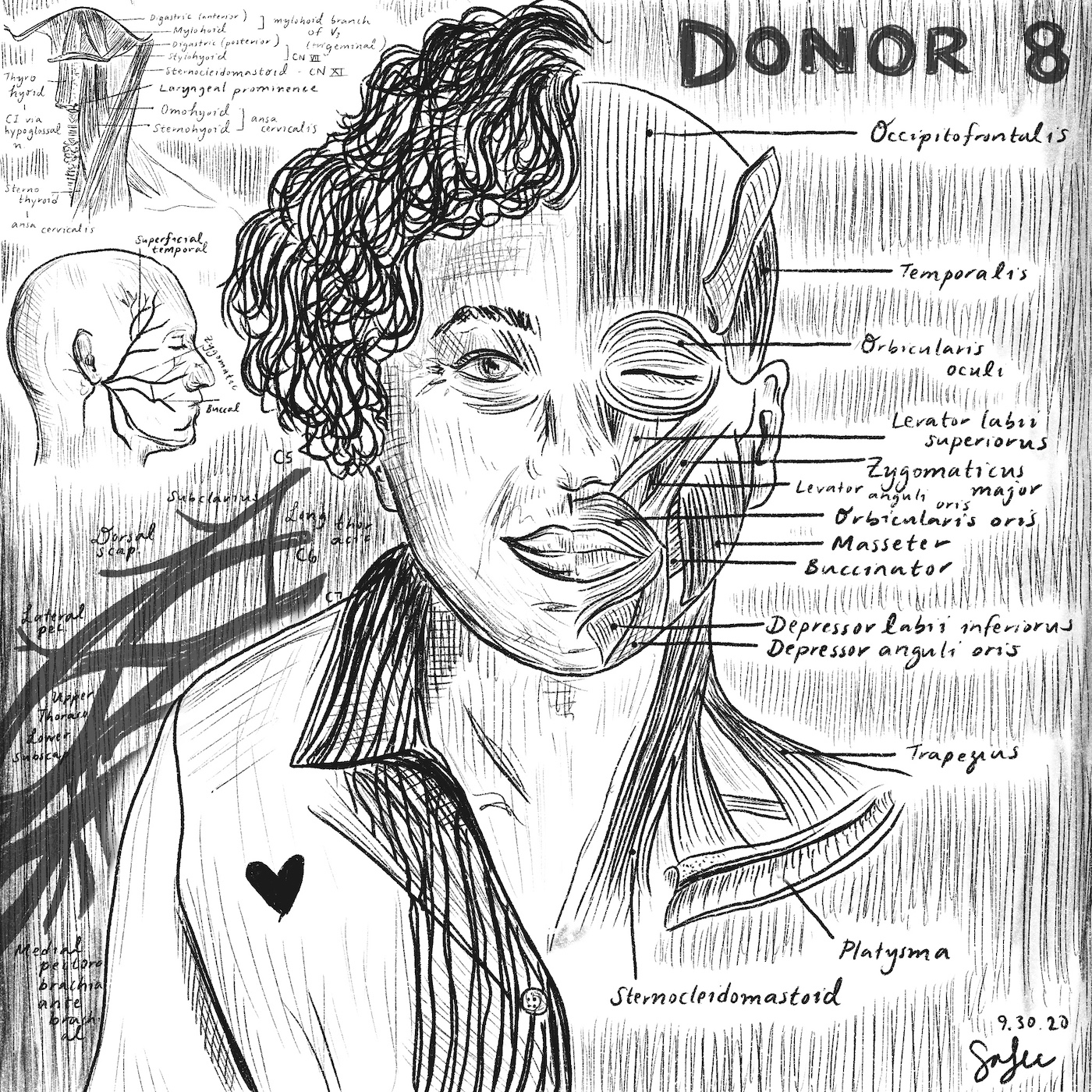

On September 29, 2021, my world started to unravel. My first anatomy lab as a medical student had just begun. I stepped foot in the cadaver lab where the pungent odor of formaldehyde clung to the air, and I was overflowing with eagerness.