The pea-sized lumps in my neck were insignificant until the day I received a call from the public health department. The voice of the nurse on the phone was muffled, but my mother’s expression said it all. Bad news.

A knot formed in my stomach hearing the word “tuberculosis.” The chest x-ray revealed that the bacteria were absent in my lungs, which meant I was not contagious. The news was a relief, since isolation was not a part of the treatment plan. Instead I was scheduled for a strict daily seven-month antibiotic treatment, the norm for patients with extrapulmonary TB. I understood the dangers of antibiotic resistance and untimely medication. Still, every pill I swallow must be in the physical or online presence of a certified health professional.

The district health care nurse arrived in a truck with a huge display of the public health department’s name. I glanced around at the houses in my neighborhood. The common stigma of public health workers and contagious diseases weighed on my shoulders. I stepped back into my house in embarrassment.

I placed the first pill on my tongue, opened my mouth so the nurse could see, closed my mouth, swallowed the pill, and opened my mouth again so the nurse could confirm that I had swallowed it. I had to repeat this for nine more tablets and this drill continued for seven days a week and for seven more months of the treatment.

The challenge to this drill came during after school events. At 5 p.m. sharp, my peers watched me place my violin down and leave for the hallway, staring down at my shoes. I would rush to my car and log onto a treatment app to video record myself taking the pills.

“Just a lymph node problem,” I would tell my classmates. Telling them I had TB felt like I would be seen as an unclean, infectious person.

I was only at my third monthly doctor’s visit when her words helped me view my own situation differently.

“There’s nothing to be embarrassed of,” she said, and I was surprised she brought it up herself.

“I too was treated for TB, and I’m aware of everything you’re going through.”

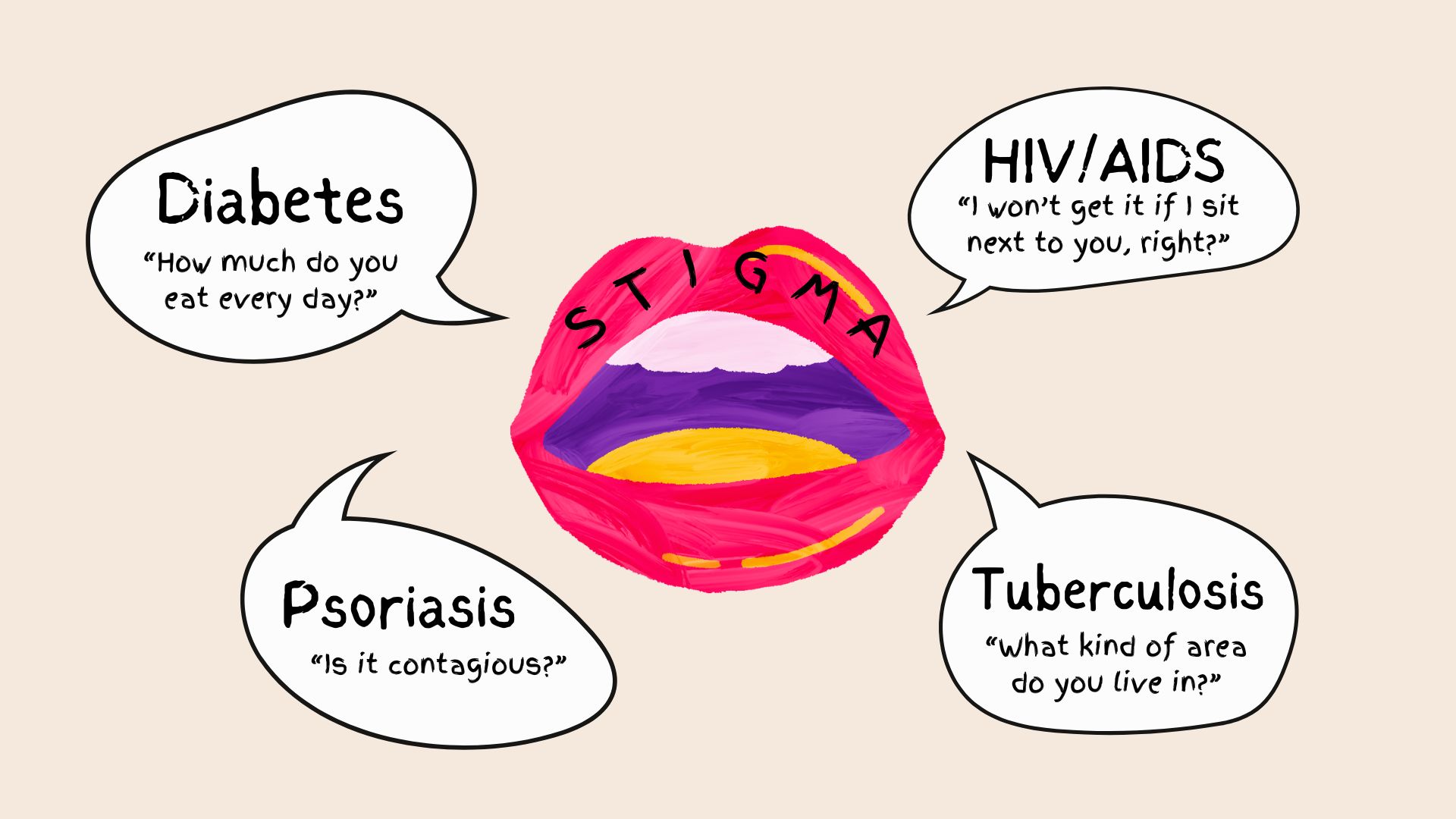

A brief conversation with her helped me realize that addressing infectious diseases among other conditions is not just about treating the disease, it is about holistically addressing the person with it. Stigma surrounding conditions like HIV and AIDS, tuberculosis and obesity continues to exist as a pandemic in the healthcare system. With so much taboo surrounding contagious and disfiguring conditions, empathy is key. Empathy comes with awareness.

Suddenly, being a TB patient did not feel like something to hang my head low for. Perhaps there is a positive in experiencing health-related stigma first-hand. Without having to learn about it in a medical ethics course, I realized that this stigma was real and widespread.

Around a year later, I accompanied a general physician in and out of patient examination rooms. I took vitals and entered patient records. Each day, I was exposed to people with different conditions, tackling their stigmatized illnesses in different ways. I recollect the amiable middle-aged man with a stringent diabetes management plan. He laughed about a blood sugar spike during his vacation cruise and joked that every family member, even his caveman ancestors, had diabetes.

The case of a middle-aged woman resonated with me the most. I greeted her as usual in the waiting room. Crinkles grew at the sides of her eyes, telling me she was smiling from behind her mask. She didn’t utter a word as she trailed behind me to the examination room, tugging at her receding full sleeves. Her loose hair curtained the sides of her face while she gave me one-word answers in the softest voice possible. It took me back to the months when not a day would go by desperately trying to conceal the small lumps in my neck using my long hair.

I held a short conversation with her, joking about the summer heat and asking her about her job as a designer. Reading out each medication name in a list of over twenty zipped me back to the time when I would swallow a handful of pills each day. She reluctantly extended her arm for me to wrap the blood pressure cuff. I understood her reluctance when I saw the pink scaly rash on her skin.

“Psoriasis?” I asked. She nodded. I took care not to hurt the area, encouraging her to wrap the cuff around her arm herself.

The doctor boomed in with a smile. Her shoulders seemed to drop at the sight of the doctor, the same way relief used to engulf me when my TB physician entered the room, bringing with her a knowing smile and a deep understanding of everything I was going through.

Sweeping away the hair on her forehead, the doctor analyzed the red, scaly psoriatic rash. The woman’s eyes darted to me, but I gave her an acknowledging smile which I hoped read as: I am not judging you and there is nothing to be embarrassed about.

She mentioned to the doctor about the itching of her palms affecting her hands-on work, and that certain fabrics irritated her skin. I could relate to her frustration when something out of control, psoriasis in her case, interferes with daily living.

The rashes on her forearm were widespread but the doctor commented with positivity that they had improved since her last visit. Her eyes seemed to light at his statement. Hope, like when my doctors had told me treatment could end two months earlier.

At the end of my shift, the doctor had a special message for me. The woman had told him that she was glad to have me greet her and take her vitals without gloves.

There are so many other stigmatized conditions that do not require personal experience in order to convey empathy. In fact, it is not necessary to experience stigma first-hand to offer care. Being in a similar situation can channelize empathy, but awareness of stigma is crucial in navigating through societal prejudices with sensitivity and understanding.

My steps were sure and steady as I walked out of the clinic and into the now-softer setting sun. I once thought that my TB chapter had to be forgotten, but I did not realize that the awareness I had gained would remain with me during every patient interaction, creating a space of comfort in a world of taboo.

Image courtesy of the author Sudharshini Prasanna.