I walk into the educational morgue that is the medical school anatomy lab with shaky knees and a fear of ghosts. At the slowest pace possible, I put on a pair of extra small gloves and a surgical mask as I ponder what the texture of an eight-month post-mortem human body will feel like. I look ahead of me at the rows of perfectly spaced corpses, once individual persons from diverse walks of life, now de-identified and subject to barbaric dissection at the hands of amateur first-year medical students.

I walk over to the group assignment sheet and hope with all my strength that I am placed with the wannabe general surgeons and aspiring forensic pathologist. Instead, I am placed with the ambitious yet squeamish future psychiatrist, pediatrician and radiologist. Perhaps the psychiatry-hopeful can become the makeshift therapist I will inevitably need after performing a double mastectomy on a deceased 100-year-old.

As I walk over to my dead patient, the formaldehyde smell (termed “the smell of death” by my twin-sister-roommate who had to endure many days of an anatomy-lab-smelling apartment) gets progressively more pungent. There are multiple barriers and layers enclosing the patient before any of us can penetrate her skin with a scalpel. A dark gray body bag must first be unzipped. The zipper is slippery and has what looks like tiny pieces of human fat on it. Then comes a light gray sheet that must be uncovered. While seemingly simple, those two steps take what feels like an eternity for the inexperienced, hesitant and frankly mortified medical student. Once accomplished, what remains is the removal of the layered white shroud: the only barrier standing between two humans — one dead and the other alive.

Beneath the shroud lies a deceased, helpless corpse, who, instead of a dignified burial, donated her body to teach the next generation of physicians. Her flesh is pale, cold and firm; one easily gets the sense that it has been preserved in many chemicals in order to retain its form. Her fingernails maintain the closest resemblance to her alive counterparts. Slightly long, hard and surprisingly similar to my own. Her face and neck remain wrapped in their own special shroud so as to not further unsettle the already aghast anatomy-lab-virgin medical student. It is by design that her face and neck are veiled in the first few sessions. After all, it is much more tolerable to cut through a chest cavity, digging through the many layers of fat, fascia and vessels to pull out a heart, with the cadaver’s face covered. In the heat of this arduous and often physically demanding task, one often momentarily forgets about its gravity and barbarism. This would not be the case had the face been uncovered the entire time during such dissections. The haunting presence of nearby eyeballs seen peripherally and felt consciously by the apprehensive medical student heightens the difficulty of the already brutal endeavor.

The most challenging part, especially in the beginning, is laying down the scalpel. My first day of lab is dedicated to learning the anatomy of the human arm which must first involve a de-skinning process. Nothing feels more wrong and counterintuitive than removing human skin. One knows that it is the assigned task and that it must be done in order to get to the muscles, nerves, and veins that need to be learned. But from a psychological and emotional standpoint, it feels like something akin to murder, or at the very least, malicious harm. “Thou shalt not murder,” commanded God to Moses and his people (Exodus 20:13). Surely “thou shalt not de-skin your fellow human” encompasses the commandment.

Yet my patient is already dead, and my task is to utilize her body for my learning. Why then the poignant dread when, on the rational level, I know that I am not causing this woman any harm or pain? I think the answer lies in a deep awareness of our shared humanity. As I reflect on the kind of life that this person (who I knew nothing about other than age, comorbidities and cause of death) likely lived, I cannot help but feel that it could not have been much different than that of my grandmother or the owner of my local hometown diner. She likely had a favorite fruit, maybe watermelon or pineapple. A favorite color, perhaps blue or purple. What was her favorite season? Her favorite flower? What were her childhood circumstances? What hobbies did she enjoy? Her worn out, wrinkled hands incline me to think she was a gardener. Perhaps a gardener who grew watermelons and purple lilies.

Of course, to think such thoughts while wielding the scalpel would make the task infinitely more difficult on the emotional level. I have found that when inside the “school morgue,” a healthy degree of detachment is often needed to be able to carry out some of the grueling dissections (e.g., the aforementioned double mastectomy done on female cadavers to expose the pectoralis muscles). However, just as important is holding space for reflection and emotional check-ins at a suitable time afterward, without which a harmful, and dare I say dangerous, numbness often threatens to take place. As physicians and humans, we must never grow accustomed to seeing harm inflicted on our fellow men — whether dead or alive. For this to occur will signal a different kind of death, the death of empathy. And how much more impactful this death would be when we, the appointed healers of society, can no longer feel the weight and sting of the suffering other. It is the ability to feel with complexity that distinguishes our species and sets it apart. In order to feel, we must learn how to patiently observe. Let us then observe, neither briefly nor dismissively, but intently and carefully, what is there, truly there, beneath the shroud.

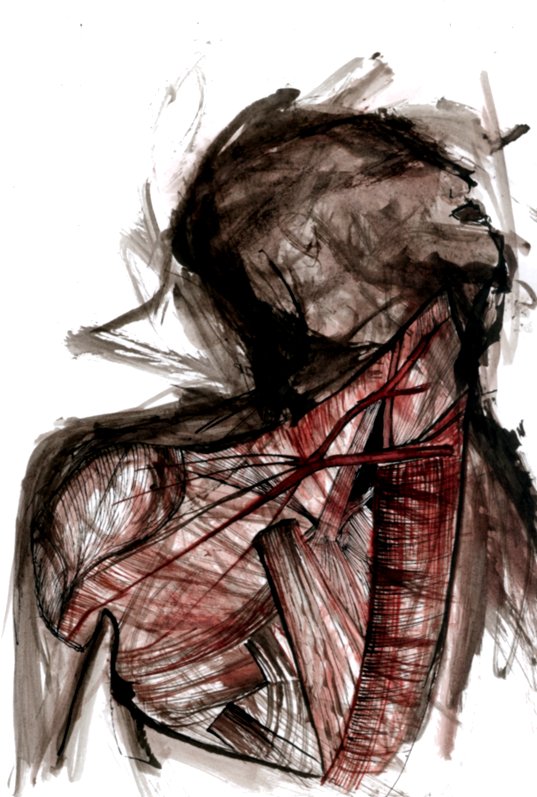

Image credit: “anatomy” (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by freizeit