Everyone warned me that anatomy block was notoriously one of the most rigorous in the pre-clinical years. I would also be meeting my classmates for the first time in person.

But we had just concluded what I thought must have been an equally intense first block of biochemistry and histology. These two classes were taught simultaneously and virtually via Zoom after our online orientation due to COVID-19 travel and institutional restrictions. We spent hours every day preparing for two lectures, then actually attending lectures, doing assignments after class and studying to try and retain all the information — only to do it all over again. This was exhausting; we were staring at a screen nearly all day, every day, Monday through Friday. At this point, we were well-versed with what is commonly called Zoom fatigue.

As I was adapting to being back in the classroom, the world raged on.

The pandemic continued and continues, and systematic racism against Black and Brown people in our communities and in health care were and are grotesquely apparent in so many ways. In response, an inaugural course on Anti-Racism, Diversity, and Inclusion before anatomy was organized by the school. We were reminded of the dark history of Western medicine, including that of cadaveric dissection.

Bodies used within the 18th and 19th century for anatomical study in medical education were primarily African-Americans, prisoners and/or the poor. We learned how the esteemed “father of gynecology,” Dr. J. Marion Sims, used Black female slaves as research subjects during 1845-1849. While stigmatization of bodies being used for dissection continued for some time, institutions still utilized cadaveric dissection as a substantial point of learning and often acquired these bodies in less than moral ways (e.g. grave robbing, of which esteemed medical institutions were historically accused). Body donation programs began to become more popular after the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA) in 1968, however, and donors began to be seen in a more altruistic and favorable light. They were donating their bodies to science.

On the first day of anatomy, we were reminded that this course was a once-in-a-lifetime experience and that we were privileged to be experiencing it. For those of us first-year medical students who might not pursue surgery nor experience physically interacting with and entering the human body again outside of surgical clerkships, the professors said this would be an intense time. We would peer into the spaces and structures that — on some level — make up every human being.

I felt extremely privileged to be learning medicine via anatomical dissection on a donor, especially considering the roots of cadaveric dissection in Western medicine. I felt grateful that our school had made it possible to have a hybrid in-person and virtual learning experience during this pandemic, thinking about safety guidelines and simultaneously prioritizing quality medical education.

Before all of that, however, I came in to meet my donor alone. It only felt right to know a little about someone with whom I would become intimately familiar with in a way that I had never interacted with a human before. I learned his name was Mr. J. I learned his age. I learned what he did (he was a CEO). My professor showed me hints of who Mr. J might have been in life but also what might have led to the end of it: patterns of tanning on his skin that showed he might have worn a collared shirt and a watch as well as positions of distention on his body. I thanked her for facilitating this meeting before we would begin the dissection process the following week.

As I phoned home to tell friends and family about this new, incredibly special experience, I referred to him by his name. I told them I was able to meet him before class, and they were confused. “Was he alive? What do you mean you met him?” I realized I used active tense language, and in subtle ways, showed that I was thinking about his existence and presence in the cadaver lab as an extension of his life.

After all, Mr. J had, near the end of his life, decided with dignity to invest his body in the education of future health care practitioners. As some of his physiological markers might indicate, he was likely suffering from ailments as he made this decision. I was and am absolutely filled with gratitude and wonder. And I wonder, might I make the same decision if I am so lucky to live a long life?

I found that I was asking questions about society and medicine, but I was also reflecting on life and death and how one may react to both.

Later, we were required to present key findings about our donors and what might have led to their deaths in a presentation titled “Your First Patient.” I realized that my first patient, Mr. J, was quite demanding: he forced me to reflect on questions about respect, responsibility, autonomy, ethics, emotion, whether I would like to go into medicine or surgery, about functions of certain nerves and their innervations, where certain structures in the body are, their clinical correlations and more.

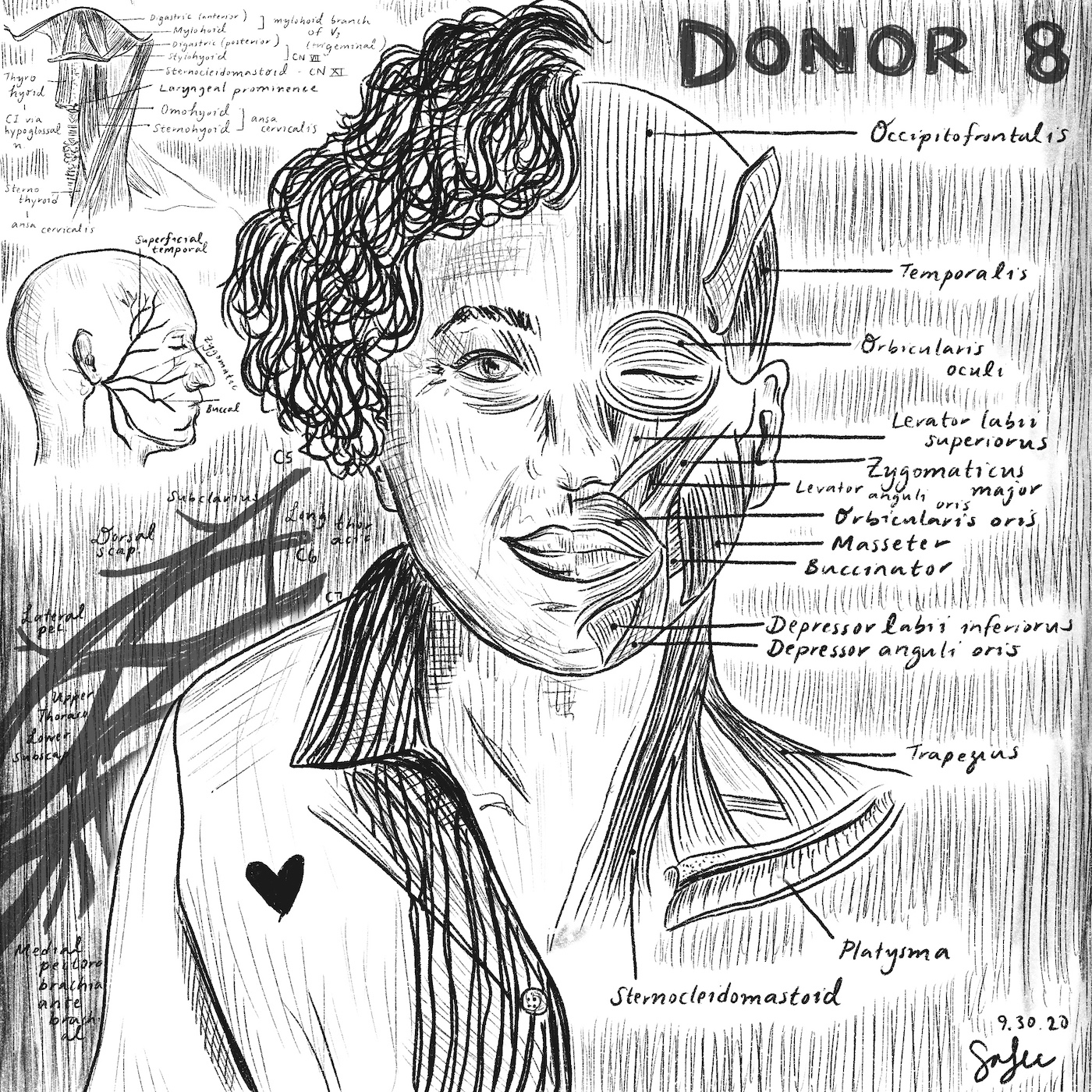

During a different week of anatomy, I signed up to help the teaching team with a dissection of the superficial portion of the human face on a different donor, Donor 8. Her name was Ms. S.

When I uncovered her face to prepare the dissection, I did not see the occipitofrontalis nor the orbicularis oris I was supposed to identify. Instead, I saw a small, elderly Asian woman. I saw her delicate eyelashes and her fine wrinkles. I saw her high cheekbones and crooked teeth. I flashed back to my own grandmother, to whom I had wished a happy mid-Autumn festival (or, Chuseok, in Korean) that morning. I saw a world in which Ms. S could have been my own family. I thought about how she was likely beloved, lived a full life and gave wisdom to her children and grandchildren. I realized that she was also giving wisdom to me and to another team of learners now. I was overcome. I did not finish the dissection.

This experience further impressed upon me the value of reflection in anatomy. I did this in written form, including regular reflections that were returned to our teaching team. The most effective method of reflection for myself, however, was one I had not expected: visual art. I drew diagrams and illustrations to visually understand anatomical relationships. I found respite from a vicious onslaught of seemingly unending studies in this way.

At times it seemed silly to invest in carefully examining the anatomy of an organ or nerve, only to copy it by hand onto sketchbook paper, especially when visual reference materials were available in textbooks and slide shows. I found the investment, however, was more deliberate and therapeutic: I actively had to assess where each note, where each branch, where each structure was. Putting the ink to paper, in the time it took to etch different structures and think about where they were in relation to each other (and any clinical correlations), I found that I was solidifying understanding of the human body with a chance to clear my mind and focus unilaterally on one task.

When I came home from my attempted dissection on Ms. S, I began studying the superficial muscles of the face. I drew them out as I usually did. I found myself, however, visualizing the skin I should have reflected from her muscles to reveal the content of tomorrow’s lecture. I realized, after I had finished my sketch, that my method of studying had evolved into something more reflective and introspective.

From Ms. S, I learned how to use art to express my thoughts and understanding of anatomy. I learned that learning medicine requires much more than just an understanding of the human body and its pathologies.

The reflective practices I engaged in during anatomy about what I am learning and how I am learning have added to my understanding of how I would like to exist as a future healthcare provider: engaged in critical yet thoughtful analysis through different perspectives. Ultimately, my first patient, Mr. J, and the other donors, like Ms. S., reminded me of how uniquely privileged I am to be engaging in medical education at this time — amid a pandemic and issues of systemic racism. The lessons I have taken from them extend far beyond the classroom.

Image credit: Provided by the author.