I was sluggishly walking into the room when my eye caught my partner hunched over her notebook feverishly jotting down notes. I walked over to the seat next to her and plopped myself down before retrieving my own notebook from my backpack. She looked over, grinned and waved before quietly returning to her work. I reciprocated the gesture before pulling out the rubric and placing it in front of me. My partner — whom I will call “Monica” — and I had to explore the various instances of dramatic irony in Oedipus Rex and relate the literary device to one used in another book we had read earlier in the school year.

“So, what should we write about for this assignment?” she inquired after about a minute of silence. “I am struggling to find a good starting point.”

“There were some examples of irony in The Things They Carried that might be good for this paper,” I suggested after staring at the rubric for a moment. “Plus, I really liked that one.”

“I was hoping to talk about one of the other books. Do you have any other ideas?”

After going back and forth about the topic for almost fifteen minutes, Monica and I decided to submit our own individual papers. Truth be told, I persuaded Monica to abandon the joint submission because I was tired of talking about it. I thought I could accomplish just as much on my own as we could together. Although I was not impudent when I suggested doing our own work, I did not deem our partnership to be particularly beneficial and did not value the opportunity to exchange ideas.

Monica and I both wound up doing well on the paper. We had an in-class, peer critique workshop the day after we received our grades for our initial drafts. Since we did not work together and submit a joint paper, Monica and I chose to critique one another’s project. I felt my jaw drop as I closely read her arguments and shuddered at how well she articulated her points. In the course of critiquing her work, I realized I missed several opportunities to learn from her way of thinking about literature. I felt ridiculous; I could have grown as a writer if it had not been for my lack of humility.

—

What does it really mean to have humility, and why should we care about it? Humility is not about seeing yourself as inferior to others based on a certain value, such as achievement or knowledge, and it is not about invariable passivity and obsequiousness. One of the most universal definitions of humility as we experience it is “a psychosocial orientation characterized by a sense of emotional autonomy and freedom from the control of the ‘competitive reflex.’” In Handbook of Positive Psychology, June Price Tangney expands on this definition by denoting humility as “an accurate assessment of one’s characteristics, an ability to acknowledge limitations, and a ‘forgetting of the self.’”

Based on the understanding of the word, most would probably agree that humility is not a trait that only benefits children and adolescents as they are growing up and learning about the world. In fact, humility is important for every stage of life because humans are continually learning and developing. The association between humility — more specifically intellectual humility — and learning is significantly positive. This association makes understanding humility important for us as future physicians because the ways we think are undergoing transformations. To this point, researchers in medical education have advanced the point that intellectual humility and good role modeling are indispensable for students learning the art and science of medicine.

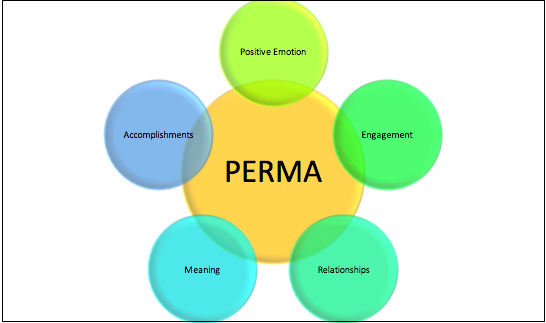

Humility is an important feature of positive psychology, a movement focused on psychological traits and qualities that promote flourishing rather than the psychopathology outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Martin Seligman was one of the pioneers of positive psychology who argued that psychological well-being and happiness derives from five core elements described in his PERMA model: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishments. What Seligman and other psychologists have shown is that humility is not an immeasurable concept and that leveraging humility can lead to better learning outcomes.

Image created by Ashten Duncan.

However, it would be misleading to omit the fact that humility is challenging to measure. Types of information bias like social desirability bias limit the utility of self-reported data collection when measuring humility. Although the current evidence base for different types of humility is not entirely robust, humility has a strong and unmistakable place in the world of medicine. We as medical students are explicitly taught skills in empathy that can lead to better outcomes for our patients, such as active listening, motivational interviewing and relational competence. While lessons in applied humility are not absent from the traditional undergraduate medical education curriculum, the concept of humility is not adequately presented in a way that shows the reciprocal benefits of humbling oneself.

We are taught to acknowledge who our greatest teachers really are in medicine: our patients. Unfortunately, not all practicing physicians uphold this belief in the physician-patient dyad. In my training, I have personally been impressed by the teachings of my clinician faculty members who insist that the answers to many of patients’ issues lie in the patient-generated history not the physician-generated assessments. Because of this, there is immense value in identifying one’s strengths and weaknesses so that you can optimally serve your patients. Contextualizing this requirement with the definition of humility demonstrates that we must relinquish some of our perceived control over medicine in order to achieve the best health-related outcomes.

So, what can we do to better ourselves so that we can achieve optimal health care outcomes? Unfortunately, the answer is not completely known yet: the empirical evidence is not substantial enough to suggest one solution. However, this knowledge gap does not preclude specific strategies from being used to strengthen our dispositional humility. Humanities courses in undergraduate medical education have been shown to enhance humility and traits related to it.

The consequence of relying on these courses too heavily is that the typical medical school curriculum does not allow for ample time to explore these topics. Frankly, it would be essentially impossible because men and women across the world spend large parts of their lives learning humanities-based skills. Therefore, it falls on us as medical students to actively seek opportunities like creative writing to fill in the gaps and — above all else — learn from those outside of medicine.

Reflecting on my experience as a junior in high school, I did not appreciate something I appreciate so greatly now: One does not know what one does not know. While there are possibly a few exceptions to this principle, the fact remains that we as individual humans are limited in our abilities to observe, control and measure the world around us. Each of us perceives life through a narrow frame, a frame that is shaped by past experiences, expectations and other sources of bias.

Our patients also have their own frames that are shaped differently based on their own histories and perceptions. Drawing from this discussion of humility, one can see that we are not so different from our patients, which may seem obvious but is too often not embraced. We are all limited; that is the natural order of things. The beautiful part of it is that it means every new encounter is an opportunity to learn something from somebody else.

As medical students, we sometimes lose sight of our purpose for going into medicine and feel that we are exerting ourselves excessively with little feedback from our environment. It is important that we remember that, while we are living through the experiences that come with our training, our future patients are also living through their own experiences. The focus of this column is to examine topics in positive psychology, lifestyle medicine, public health and other areas and reflect on how these topics relate to medical students, physicians and patients alike.