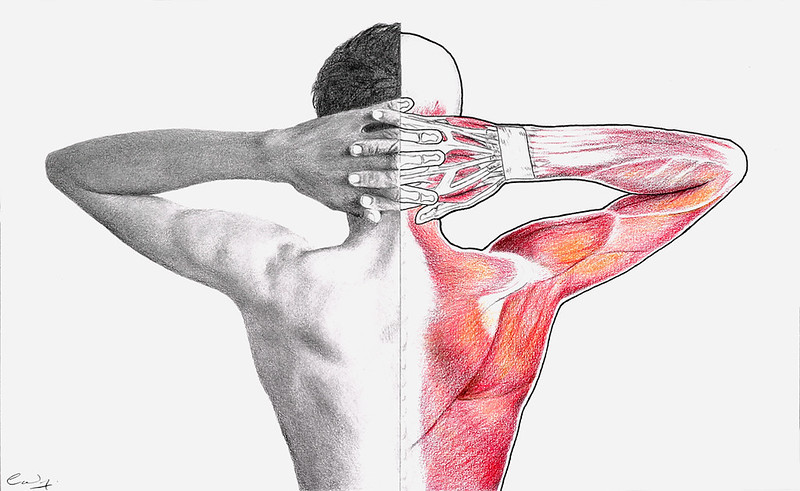

As I took my shirt off this morning to shower, I noticed my teres major muscle in the mirror — or more precisely, I identified it for the first time. Though I had been aware of the ovoid prominence below my deltoid for years, up until that moment, I had never actually afforded it any form of scrutiny or reflection beyond my passive awareness of its existence. My teres major muscle was nothing more than “that fleshy egg under my shoulder” — a vestigial lump of little consequence or utility. Until last week, I had no idea that it had helped rotate and adduct my arm faithfully for over 20 years.

The Teres Major Phenomenon is not unfamiliar to me. In fact, my identification of my teres major muscle was, somewhat ironically, a relatively minor case of this phenomenon. Since the start of medical school, I feel as though I have been slowly developing a new sense of perception — like the infrared sensors of a snake or the electroreceptors of an elephantfish. When I look at people, I often perceive details that I would have previously overlooked and instinctively extract their clinical or physiological significance. While walking through the grocery store a few months ago, I recognized xanthelasma on a shopper’s eyelids and knew he had high cholesterol. A few weeks later walking on campus, a young boy with Duchenne gait. Most recently, a resting tremor in an elderly cashier — the ominous mark of Parkinson’s disease — which, for multiple reasons, tore at my heartstrings in a way that it could not have prior to my first year of medical school.

One of the most interesting aspects of this new sensory modality is that it not only enriches my present lived experience, but adds new meaning to my memories: I can envision what my displaced scaphoid fracture must have looked like after my bike accident during my freshman year of college and imagine the biochemical actions of my osteoblasts and osteoclasts while my arm was in a cast. I understand why my friend’s niece developed “tea-colored” urine during an E. Coli infection and how her physicians treated her kidney failure using dialysis. Perhaps most importantly, I now understand why, in 2nd grade, after persistent episodes of nocturnal itching, I was indecorously roused in the middle of the night by my mother brandishing a flashlight in one hand and a strip of scotch tape in the other (pinworms).

More eerily, I now realize that my relative’s hooded eyelids, cleft palate and developmental delays indicate that he may have DiGeorge Syndrome and what it meant when a miscarried baby in the family had a “webbed neck.” I understand how my grandmother developed stomach cancer after years of undiagnosed and untreated H. Pylori infection and why she died. I recognize what my grandfather’s recent diagnosis of Stage IV chronic kidney disease really means and the implications of his choice to abstain from dialysis.

It feels as though I have been given the keyword to a cipher that has concealed secrets about my life and the lives of those around me until now. In some ways it feels invasive and unnatural, as though I have X-ray vision that I cannot turn off, and so I see things that I should not be able to, even if I do not want to. At the same time, the process has also been beautiful and enlightening, at times almost poetic — a Homeric Odyssey riddled with fear, joy, triumph, disaster and innumerable challenges and rites of passage. On each journey through the mysterious realms of anatomy, pathology, physiology and clinical medicine, I have brought something back with me: an unusual and intriguing fact, a pearl of practical wisdom, a more profound appreciation for the beauty and tragedy of the human experience and often a sense of my own inadequacy.

Each morning, a new person looks back at me from the mirror: one who has studied the arcane lore of the primordial biochemical pathways, appreciated the finely tuned mechanism of the brainstem, plunged elbow deep into the human thorax and witnessed firsthand the euphoric chaos of birth and solemn serenity of death. Though I cannot describe it precisely, there is something humbling, a dismaying flash of understanding, an irreversible alteration in the soul and above all, a sad — yet compelling — yearning that comes with learning the art of medicine. As my knowledge and experience deepen I feel a paradoxical blend of privilege and dread as over and over I become progressively immersed in that beautiful, terrible, ineludible truth: the Teres Major Phenomenon.

Image credit: Drawing: Outside-Inside (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by Denish C