I scowled at my computer screen as I nibbled on a granola bar. My eyes ran across the same paragraph for the fifth — or maybe even sixth — time in the span of 15 minutes. Though I was giving my undivided attention to the paragraph, I could not move past it; I was at a complete loss for how to convey my next point. After another few minutes, I sighed and placed the wrapper of the granola bar on my cluttered desk before retreating from my writing and going out into the backyard to get some fresh air.

I had been working on the story for over three years and had only composed about 110 pages. When I was in fifth grade, I wanted to write a book about two national park employees who were essentially wildlife conservationists on a mission to save grizzly bears in Alaska. Over time, the premise of the story evolved, turning into a much more convoluted tale of mafias, government conspiracies and fantastical situations set in rural Alaska.

Although I refused to acknowledge it in the moment, I knew what the source of my writer’s block was: I was trying to write about things that were not even remotely grounded in my own experience. Although it is debatable whether fiction writers necessarily benefit from using their own experiences to create fictional worlds, for me it has proven to be the best policy. The detached style I was using led to me writing stilted, derivative and sometimes depthless stories. It also caused me to run out of ideas very quickly, like a well drying up in the heat of a summer drought.

To this day, I still have not finished writing the conservationists’ story. In many ways, I felt like I was lacking the energy needed to overcome the barriers associated with the writer’s block in order to get to the next step in writing the book. As I have gotten older, I have found writing about topics that are thoroughly familiar to me is much easier, requiring much less energy to make headway. Indeed, over time I have come to think of many problems in my own life and the world around me in terms of the energy required to overcome them.

—

When we think back to our undergraduate organic chemistry courses or even concepts from physics courses, the first idea that might come to mind is how energy is required to do work and drive change in natural and artificial systems. Whether the change involves two chemicals reacting with one another or an object being displaced in space, a certain level of energy is necessary to produce observable change. Not every form of energy is usable in a given system, and often usable forms of energy are converted into unusable forms, such as heat. This fact suggests that indiscriminately applying energy to a system — even above purported threshold levels for producing a change — does not guarantee a change will occur as expected. In fact, the application of sufficient unusable energy can destabilize systems (e.g., excessive biomechanical energy producing a fracture in a bone).

So, why should we as future physicians care about all of this? There are admittedly some direct applications of these concepts that are apparently germane to clinical medicine: the energy dose required for cardioversion, the impact of external energy on anatomical structures, and the connection between increased energy intake and adiposity. But, what if I said that the concept of energetics could be readily used to describe describe humans’ ability — or lack thereof — to make health behavior changes? While humans on many levels are much more complex than the systems that are typically used to illustrate how energy generates change, it does not mean that we are so different from the environment that surrounds us.

Image created by Ashten Duncan.

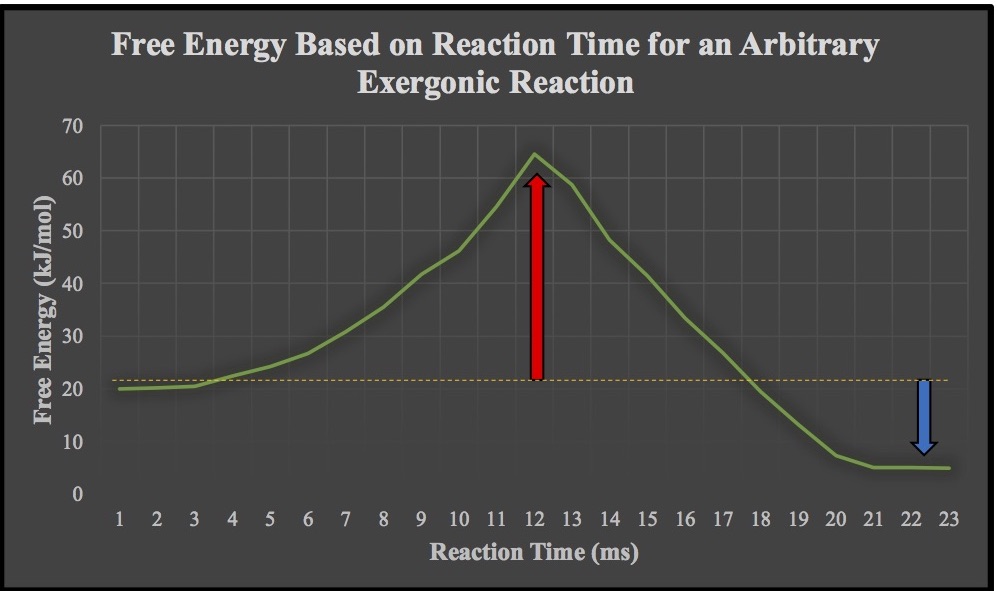

Before drawing parallels between microsystems and macrosystems in the context of energy, let’s think about something from organic chemistry that most of us have compartmentalized in the back of our minds: chemical thermodynamics and free energy. One of the most important concepts is that exergonic (i.e., energy-releasing) reactions are spontaneous and result in the formation of more stable bonds. In the image above, the classic scenario is illustrated: reactants undergo a reaction that results in increased energy (shown by the red arrow as the activation energy) and the subsequent formation of a high-energy transition state. Thereafter, the reaction moves to completion, leading to the one or more products with a lower energy level (shown by the blue arrow). The primary reason for why exergonic reactions are spontaneous and energetically favorable is because the products are more stable than the starting materials.

In the context of health behavior change, a patient’s initial set of behaviors could be analogized to the “starting materials” and their modified behaviors (e.g., smoking cessation) to the “product.” What lies in between these two points is an investment of energy in order to drive the “reaction.” An important consideration in all of this is that many health-benefiting changes as “reactions” are not “exergonic” because they so often consume energy instead of releasing it. The life course epidemiology perspective upholds that behavioral patterns are not simply the result of a single “reaction” (i.e., health-related influence); the reality is that numerous intrinsic and extrinsic factors over time influence a person’s behaviors. Nonetheless, the principles of energetics apply and help to explain why behavior change can be difficult to achieve, especially those whose environments do not accommodate the change.

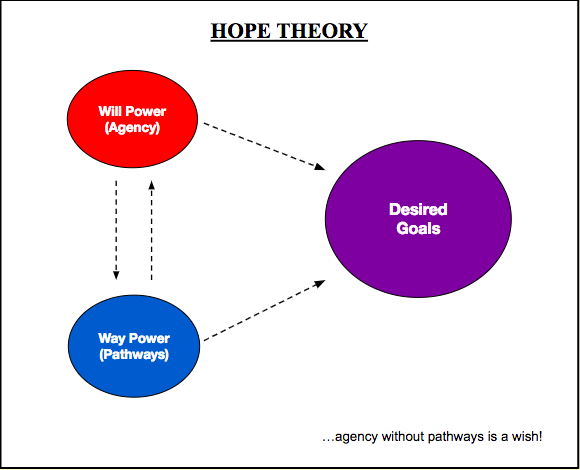

As future physicians, we will be addressing patients’ health-related needs in order to improve their quality of life. With the ever-increasing prevalence of multimorbidity that is attributable to modifiable lifestyle factors, understanding how to influence patients’ behavioral patterns is critical. One social-behavioral concept that dovetails nicely with chemical thermodynamics and energetics more broadly is hope theory, which I covered extensively in my previous installment. In brief, hope theory describes how the cognitive appraisal of the factors involved in goal pursuit influence one’s ability to set and pursue goals. The image below summarizes the theory and the net movement of goal-directed energy.

Image created by Ashten Duncan. First appearance in “A Case for Building Hope in Medicine” on in-Training. Adapted from C. Snyder’s hope theory framework.

When I was trying to write a book years ago, I encountered an obstacle in which the “activation energy” for the “reaction” was too great. As a result, all progress was halted, and I became unable to flesh out the story. With more life experiences under my belt and new sources of inspiration, it is much easier to come up with ideas for stories. Drawing on these experiences to lower the energy threshold for creative writing is analogous to an enzyme catalyzing a chemical reaction. What this lowering of energy thresholds means on a practical level is that health care providers can capitalize on sociocultural and intrapersonal factors that mediate, moderate or otherwise influence the relationship between a provider’s recommendations for health behavior change and a patient’s rate of adoption of those recommendations. Many providers share the struggle of not getting their patients to adopt more healthful behavioral patterns; a reason for this could be that patients feel that they need to invest much more energy into the change than they can reasonably manage.

Regardless of what health behavior we consider and its downstream consequences for a person’s overall wellbeing, there is a reason why people do what they do, and some of these reasons are far outside of the control of the patient. In fact, almost all non-pathological behavioral patterns have a rational basis to them in that they are driven by trends in what is basically “free energy.” This is why empathy and shared decision-making should always be part of the work we do: behavior change is achievable when we understand the “mechanism” of the health-related behavior. The more we understand where patients are coming from when they come to us, the better we can redirect the energy contributing to less healthful behaviors (e.g., physical inactivity) and use that energy to achieve health-related goals. By taking a note out of the chemistry textbooks, we may better be able to help identify the dynamics underlying patients’ behaviors and use our knowledge of energetics to make change favorable on more than one level.

As medical students, we sometimes lose sight of our purpose for going into medicine and feel that we are exerting ourselves excessively with little feedback from our environment. It is important that we remember that, while we are living through the experiences that come with our training, our future patients are also living through their own experiences. The focus of this column is to examine topics in positive psychology, lifestyle medicine, public health and other areas and reflect on how these topics relate to medical students, physicians and patients alike.