08/21/2020

My dear husband, David,

I still feel the corner of my mouth turn up whenever I get the chance to address you that way. We are three weeks into our marriage, still trying to figure out how to not kick each other as we’re falling asleep and taking turns killing crickets in the basement. If you ask me, I’ll always say it’s your turn.

I love watching you wake up — your big, creaky stretch as you sit up, while I think, “you’re too young to sound like this.” In the morning, the aggressive beeping of the coffee maker and your elephantine nose-blowing are my trumpets announcing a new day, which is curiously contrasted with our house being lit only by the soft flickering of candles and the orange glow underneath the microwave. I guess this is just our kind of ambiance.

I’m grateful for these moments because they remind me of all the days we spent apart, while we lived hundreds of miles away. During that time we spent eight hours on the phone … finally telling each other that we wanted to get married. I rarely got to see you on Wednesdays, since our time together was almost exclusively reserved for the weekends we could travel. Now, in quarantine, being in different rooms can feel like being far away. It’s a gift to experience an entire day with you.

This morning, I’m thinking about last year. I wonder if there’s a canyon cut into the granite of my brain where the river of repetitive thoughts crash against it. I think the memories that I dwell on appear in my mind because there are important details and perspectives begging to be seen or understood. That’s how I feel about parental nagging and cliché quotes on mugs: “Be the change you want to see in the world,” “What lies behind us and what lies before us are tiny matters compared to what lies within us,” and, “If you’d just do the darn thing, it’d be done by now.” We see and hear these things so often, but rarely take the time to meditate on the wisdom they have to teach. This truth inspires me to be a more eager reflector on my past.

I hear a chirp from the bottom of the stairs which pulls me out of my thoughts as I pour myself a cup of coffee. I set down my mug, take a deep breath, and march down the stairs. Today is as good a day as any to start following my mom’s advice.

Yours,

-M

02/04/2019

Super Bowl,

I think it’s time for me to be honest: I hate you. Okay, maybe hate is too strong a word, but I can safely say I have more negative feelings about you than the average American likely does. My fondest memory of you is the time I ate my first homemade ice cream sandwich while watching Drew Brees mow down the Colts. I’ve had my fair share of store-bought ice cream, you know, the ones with two dark brown rectangular slabs with odd perforations awkwardly enveloping white, flavorless, melting fluff? Delicious, of course, but the experience of devouring a freshly churned vanilla bean custard between warm chocolate chip cookies is one that I’ll never forget. This was closely followed by my godfather almost choking on a jalapeno popper. It’s always one step forward, two steps back with you.

I had planned on going to a small get-together to watch your final moments when David called me in what sounded like a drunken stupor.

“I’m lying on the floor of my bathroom,” he mumbled

“Too much fun?” I asked. Please let the answer be yes, I hoped silently in my mind.

“No, I just keep falling and when I try to stand.” I heard him shifting, trying to find a more comfortable position.

Since last week he’d been making a lot of progress, so much that I’d almost convinced myself that everything was fine. He had called me at 4 a.m. on January 24, saying he had no control over the right side of his body, was seeing double and throwing up. It took all my self-control not to blurt out my suspected diagnosis. I had an interview at a prospective medical school on January 25, which I ended up leaving early to drive 300 miles to his apartment. I spent the weekend lying next to him as he drifted in and out of consciousness.

“God,” I prayed through tears, “please heal him, please save him,” hoping that you might open his eyes and the world would stop spinning.

One step forward, 99 steps back.

-Anger

02/05/2019, 5:50 p.m.

Dear 1210 CHEM,

You smell like a high school boy that has, once again, forgotten to put on deodorant. Your dusty air and scruffy chairs that haven’t been reupholstered since the Reagan administration do not exactly create the temple of learning I’d envisioned college might be. You have a folksy charm that I’ve grown to appreciate, but it’s spooky to think that this is the room where Ted Kaczynski used to teach physics.

I’m standing outside your doors, nervously tapping my foot on the white linoleum floor. I barely slept last night. Between calling David just to listen to him breathe on the other end of the phone and halfheartedly building up the energy to try to care about this molecular biology exam, I am in some sort of day-dreamy yet hyper-focused zombie mode. I am trying to go about my day normally, getting periodic updates from him saying he was going to the back doctor to get re-evaluated.

“If they tell you that you have vertigo again so help me…” I hiss under my breath as I add another smiley face to my text message.

My exam is set to begin at 6 pm, as my classmates and I walk across your threshold to find a seat. Time: 5:52. I sit down, put away my notes, get out my pencils. Time: 5:54. Finally, I take my phone out of my bag to put it on silent, when a text from you appears: “I’m in the ER. I had an MRI and they said I had a stroke. I’m being admitted.” Time: 5:56.

“Please, put your phone away,” one of the graduate students proctoring the exam calls out to the class from the front as they begin passing out exams. The surface of my brain is completely frozen in time, while the core is erupting with heat and frantic energy. It’s a two-hour exam, and normally I would stay until the very last moment under your flickering lights to triple-check answers, but a lot of things are different about today. I complete the exam to the best of my ability and race out of the building, moving so fast it’s a marvel my sneakers aren’t generating smoke.

He and I became friends and fell in love, in part over our shared love of running. I think he would be proud to see how quickly I cover the ground between the chemistry building, my house on campus and my car.

I’m sorry I pushed your doors so hard as I was leaving; they didn’t need another dent, but I doubt anyone will notice it.

(Un)apologetically,

-Roadrunner

02/05/2019, 11:48 p.m.

Dear David,

I made it to Indy safely, despite the pouring rain and tornado sirens blaring as I sped down the highway. I finally arrived at your room on the 8th floor of the hospital. When I walked in, your nurse was trying to put an IV catheter in your arm. We both know how much you loathe needles, so I put my things down and kissed you on the forehead. I held your other hand while she finished her work, which took quite a bit longer than either of us would have liked. She left a few moments later and we listened to the quiet beeping of telemetry monitors, watching the ECG tracing wax and wane as your heart was beating. I put my head on your chest and listened, just in case technology was playing tricks on me again.

Your friends and family had already left before I arrived because you knew I would be there soon. I don’t know if I remembered to tell you how loved that made me feel. We were both exhausted, so I settled into a makeshift bed on the pullout chair next to you, and held your hand as you fell asleep. I was worried you would shift and pull the IV out of your arm, but you stayed peaceful until you got woken up around 3 a.m. for another blood draw. A hospital is no place for resting, but to my relief, you fell back asleep again without much fuss.

We would leave the hospital a few days later with lots of questions and a couple of answers. Your neurologists said this could have just been an isolated incident, or possibly underlying multiple sclerosis, a chronic degenerative neurological condition that I’ve watched overtake my grandmother’s body for the past decade. There’s no way to know and nothing to do right now, except go to sleep and wake up each day, thankful for clear sight. I pray that one day we’ll be able to share our days from less than 300 miles away.

Although this experience is life-altering, I found myself repeating that it doesn’t change anything for me. You are the person that would teach me what it means to love someone the way my mom loved my dad. The four walls of a hospital, and all that happens inside them, changed everything and nothing at all.

I tried (in vain) to sleep that night, eagerly waiting for your eyes to open again.

-Yours

10/04/2017

Mom,

When I called you, I already knew what you would say.

“Dad’s gone.”

After a few moments and some words that I don’t remember, I threw open my door and took off down the hallway without wondering whether or not it would close. I was thankful no one was awake to see or speak to me; I’m not sure what I would have done. A soft breeze greeted me as I stormed back into the still-dark autumn morning. My shirt was already soaked with sweat from the run I had just returned from, and the wind hitting my arms might have left me with goosebumps had my body not been aflame.

After yanking my bike off the rack with freshly inflated tires, I took my flight down Hill Street, as if I was making an attempt at the green jersey in the Tour de France.

I arrived at the house, propped my bike against the garage, and sat down next to you with my arm around your shoulders, just listening to our breathing. I remember having the strangest feeling of happiness in this moment. I was smiling at the thought of my dad’s body being relieved of its suffering and redeemed in Heaven — no more infusions, surgeries, nausea, weakness or body falling into disrepair. This was followed by tears; so much was lost for that peace to be gained. But I was just so happy to share this moment with you, to hold you while our hearts broke.

“Do you want to see him?” you asked, after a few minutes.

I nodded yes. We walked inside the house and up the stairs, feeling our feet sink into the carpet with every step. I was preparing my heart to see my father for the last time. Growing up, friends would always say I take after you: curly brown hair tinted with auburn, dark eyes, freckles, serious eyebrows and bravery in the face of adversity. Saying goodbye to him was one of the most impossible moments of my life.

Would you have done anything differently, had you known that the love of your life and father of your children would die 9 days before your 27th wedding anniversary? Your answer has never changed: you would go through this struggle and this loss a thousand times over if it meant getting to be with this person. I wondered what it might be like to have a love like that. You smiled, gave me another hug and made us some tea. The sun was high in the sky as we sat on the porch again and we sighed with exhaustion; this lifetime of a day is only half over.

We’re going to make it.

-Mal

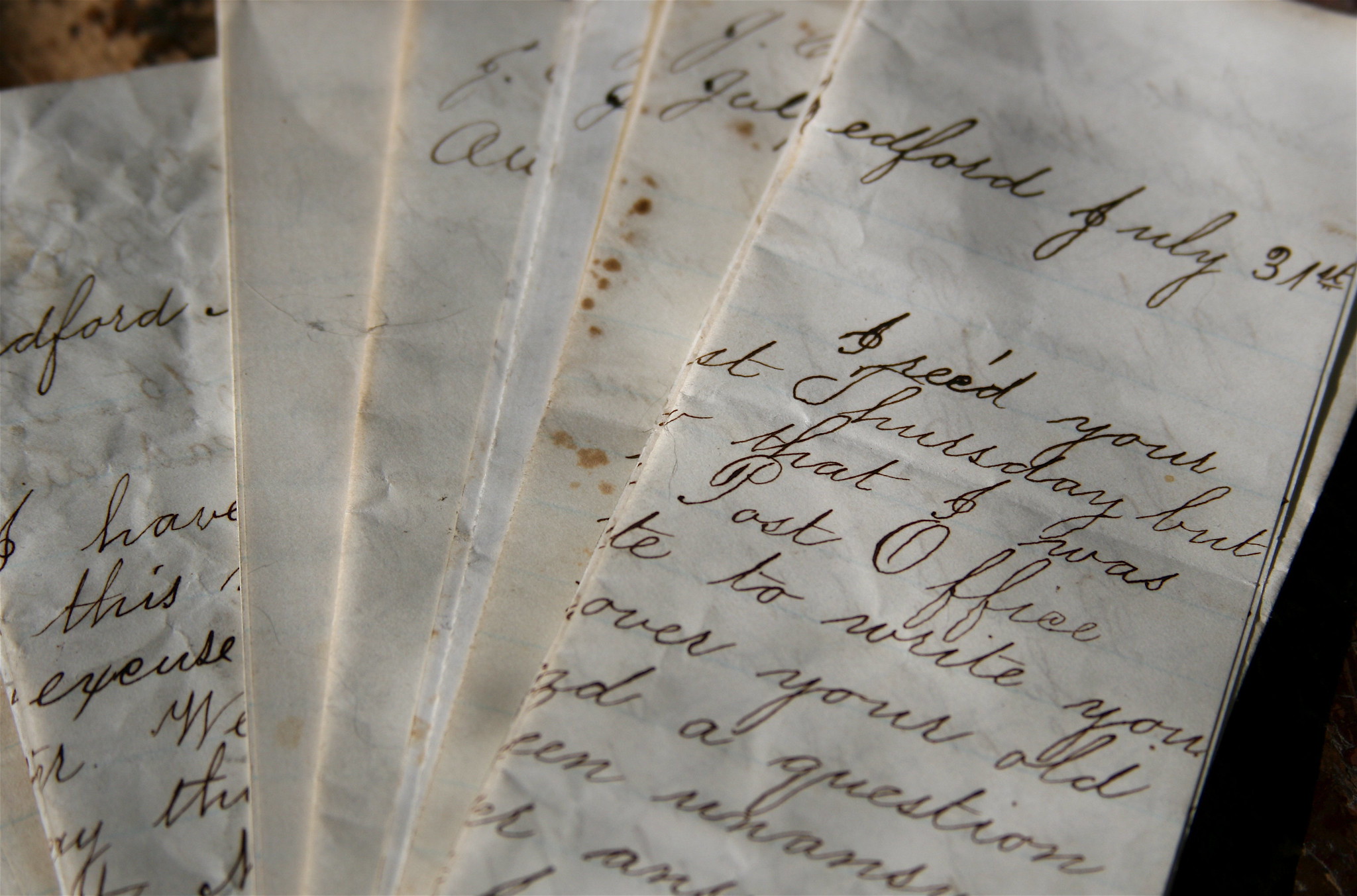

Image credit: letters (CC BY 2.0) by Muffet