I sit, staring at my color-coded diagram of the nephron, trying to ignore the texts lighting up my phone screen.

“Okay, furosemide works on the Loop of Henle. Furosemide’s brand name is Lasix, so I’ll remember L for Loop,” I mutter to myself.

My phone dings again, it’s cheery tone no match for my current mood. Finally, my curiosity gets the better of me. I shove my diagram away, pulling the phone toward me. Swiping it open, I see where the slew of texts is coming from: “We are family,” the WhatsApp group chat that my huge, Irish family has used since 2013. It has been a stalwart over the last decade: a place to send recipes, addresses, or first-day-of-school photos. My mom is one of seven children, who all have spouses and children of their own. She is the only one who moved to the States. The WhatsApp group is like a lifeline, tethering us to the only extended family we have, an ocean away.

Scrolling through the messages, I feel heaviness settle into my chest. I click on the first photograph I see. My family all smile back at me, dressed in their celebratory best: suits, dresses, JoJo bows in all the little girls’ hair. Gold and silver balloons are scattered around their feet. I know from my mother that her sisters and she arrived early at the venue to decorate. My grandfather stands in the center of the photograph, his face cracked wide open with a happy grin.

He is 80 years old today.

I zoom in on my grandfather. He looks well, wearing his best suit. The photograph does not show his tiredness or the toll his congestive heart failure takes on his body. He is practically glowing, warm in knowing his family is all around him. Distantly, I think about the pathological mechanisms I now understand: how the macula densa cells of his kidneys sense less salt, driven by the low blood pressure coming from his heart. How this low blood pressure triggers his juxtaglomerular cells to release renin and sets off a cascade of hormones that ultimately, will make the disease process worse. I think of the Ezy Dose weekly pill planner he uses to hold his medications, each little plastic box containing a rainbow of pills. I’ve heard him mention Lasix before. He calls it his water pill, and he hates it.

Instantly, the drug’s mechanism of action makes resounding, horrifying sense.

I blink past the sudden rush of tears in my eyes. My grandfather had known I wasn’t coming. I have an exam in a week that is worth 30% of my grade, and I couldn’t fly in for his birthday, as much as I wanted to. He told me he wouldn’t want me to risk my grade, that it was too important. He said he understood, and that he would see me soon.

I quickly count the people in the photograph, all my mom’s siblings and various cousins and in-laws. In total, there are 26 people. My aunt, who is heavily pregnant, sits in the front of the group, her hands resting protectively on her baby bump.

Even the unborn baby is there, and I am not.

I suddenly feel lost in my loneliness, in my otherness. I will be the first doctor in my family, and normally, this fills me with joy. Whenever I get tired of the long hours studying, I only need to remember how proud my family is to find the will, the strength, to keep going. I think of my parents, who moved to the States to give me these opportunities. I think of my grandmother, who lights candles in her local church before every one of my exams. I think of my grandfather, who answers my Facetime calls with a merry “How’s Doctor Hamill?”

Today though, all I can think is that I am the only one not there.

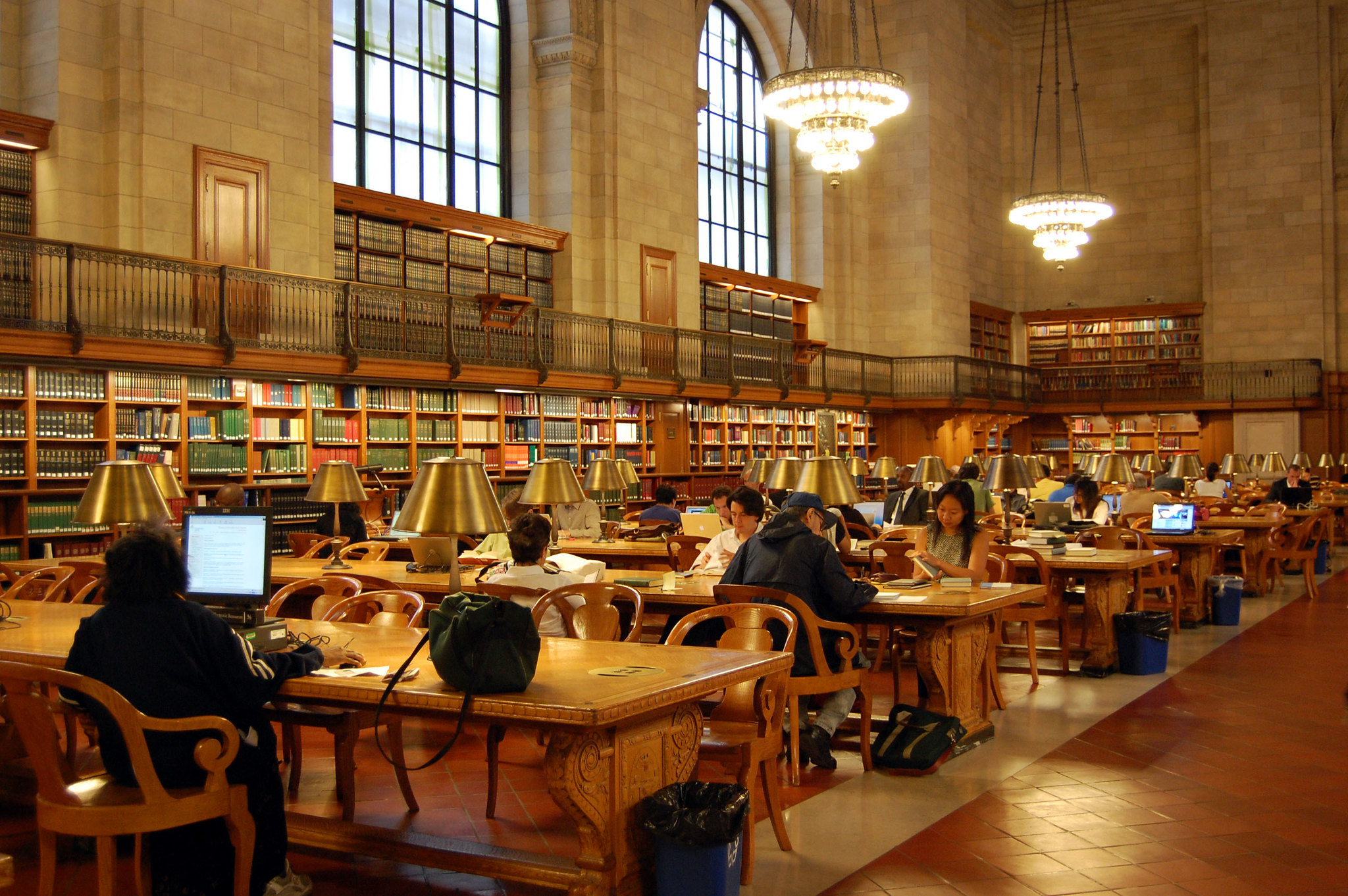

I grit my teeth, swiping at my eyes. I need to snap out of this. I need to focus, or else I will fail this exam and this really will have been for nothing. I can wallow and feel sorry for myself later, once it’s over. Taking a deep breath, I exit the WhatsApp chat and put my phone on Do Not Disturb. I pull the diagram in front of me again, leaning over it, until it is the only thing I can see.

To this day, I know all the parts of the nephron.

Image credit: Reading Room (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by su-lin

WiTTY Wednesdays is an initiative showcasing the works of our Writers-in-Training Program writing interns. WiT is a year-long internship for budding medical student writers. Our interns receive intensive, one-on-one mentoring from our medical student program directors and publish at least 3 pieces during the course of their internship. If you are interested in learning more about the program, please contact us at editorinchief@in-training.org.