Medical school is scary.

Intimidating.

Daunting.

Sometimes I wonder how I am standing here,

Already in third year,

Still thinking they made a mistake by letting me in.

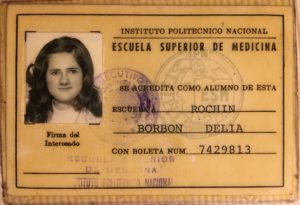

I was born and raised in Mexico and only spoke Spanish until I was about 15 years old. I moved to the United States in high school, struggled because of the language barrier and lost my confidence. I got into medical school in my late 20s through a bridge program because my MCAT score, especially the reading part, was not good enough.

Somehow, I managed to make it through my basic science classes and eventually finished second year. Then the USMLE Step 1 happened. I do not believe I have ever felt so inadequate as during this time. I studied passionately for 12 to 16 hours every day for five to six weeks only to find that I ran out of time during each block in my exam because my English reading proficiency will never be like a native speaker. My comprehension will always take me a little longer. Even before getting my score back, I felt like a failure, since I knew I could not perform to my potential and that took a toll on my confidence.

Soon after, I started rotations. The nervousness combined with excitement kept me going for the first couple of days of my rotation, but that feeling of failure followed me. I had to relearn another language of OB/GYN acronyms and was daunted by all the things I did not know and the responsibilities I felt like I could not accomplish. Then, an attending forced me to present a patient who I was not familiar with and proceeded to demolish me in the middle of rounds with other students, residents and nurses to witness. A lot of what he said is a blur, but somewhere I remember he said he could not understand what I was saying because of my Spanish accent. That is when I realized I should not be here. Immigrants are not supposed to go to medical school, they are supposed to find a stable job, have a family and give their children an opportunity to grow up in this nation and live the “American dream,” right?

What am I doing here?

Should I even be here?

The medical student impostor syndrome had never been stronger or more discouraging. I was so afraid about faculty finding out about me and dropping me from the program. The impostor syndrome I experienced was extremely debilitating and, at some point, it handicapped my performance in my rotation. I even doubted the way I walked; I constantly looked at my badge to make sure it said Ana Meza-Rochin and not someone else’s name. I even told some doctors that I would rather shadow and observe instead of seeing a patient on my own because I felt so afraid and incapable of doing so whereas, a few months back, I would have fought to be given the responsibility and opportunity to show them what I could do. I was not that brave girl who fought until she reached her dreams anymore. I was a different person.

Thankfully, I had great preceptors who taught me with patience and made me feel comfortable doing basic tasks such as finding a baby’s heartbeat with Doppler ultrasound, measuring fundal height or asking simple obstetrics questions. Later, I was sent to see a new obstetrics patient by myself. She had a Hispanic last name, and her mother accompanied her. When I walked into the room the patient spoke to me in English, and I followed along. I did the typical questions and physical exam, and then the midwife came to see the patient.

As the midwife asked the patient about information in the chart, the patient’s mother, who had been carefully observing me and looking at my badge, whispered to me, “Do you speak Spanish?”

I moved closer to her and away from the other conversation and whispered back, “Yes.”

Smiling, she asked, “Are you from Puerto Peñasco?” She was referring to a small town in Mexico.

Confused, I said, “Yes.”

Before I could ask her anything else, she asked, “Is your mother Dr. Rochin?”

I stood quietly for a couple of seconds in denial echoing that faintly familiar name in my head, kind of like trying to recall a dream. “Yes,” I answered.

“Your mother was my doctor in Mexico, and she delivered my children including her,” as she pointed to the patient. “It is amazing to see the daughter of my doctor taking care of my daughter and her child.” She said that with the biggest smile and with tears in her eyes.

Speechless, I walked out of that room and sobbed. Something happened to me at that moment. First, by reminding me who my mother was, I was reminded of who I was, which I felt like I had forgotten. Second, I was reminded of the “why.” It was like something fell from my eyes that allowed me to see further than my own frustration, fear and feelings of worthlessness. I understood where I was coming from, what it meant for me to be standing there regardless if I felt competent or not and where I was going. The what am I doing here? question due to feelings of inadequacy became more like a WHAT AM I DOING HERE? out of excitement for doing the impossible.

Immigrants often do not get the chance to stand on the top of mountains of opportunities, of distinguished careers, of success, of believing they can do anything they can dream of not only for their children but also for themselves. I realized I had been focusing on all the things I did not know — on all the ways I felt awkward, not ready, not worthy, helpless — instead of focusing on how far I have made it, the great privilege I have to be training to be a doctor, all the lessons hidden in each day’s struggles and the new adventures awaiting me tomorrow. That just blew my mind.

Third year is a fun, hands-on year, but also a very challenging one. Challenge comes in different forms and directions for each student, and sometimes it feels that we are the only ones going through adversity. I believe it is important to focus on the “why” and on the good. Always look forward, but also look back. Looking back is an essential reminder of the great obstacles that we have overcome, all the growth we have endured and all the things we now know. It is hard to realize those things when we are only surrounded by great physicians who constantly challenge us to think more critically and ask more of us each time to make us better doctors. Looking back reminded me of why I am devoted to where I am going and thankful for the challenges that have brought me to where I am.