Yash Shah (5 Posts)

Yash Shah (5 Posts)Columnist and Medical Student Editor

Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University

Yash attends Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, PA. He pursued a Bachelor of Science in premedicine at Penn State University. Prior to attending medical school, Yash worked on clinical and translational oncology research at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He has long-standing interests in contributing to medical education, advancing health policy, and working with cancer patients. He enjoys playing tennis, rooting for the Eagles, reading, and traveling in his free time.

COVID Chronicles

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a tremendous challenge to our community – certainly from a health perspective, but also in nearly every other aspect of daily lives. Our daily routines were upended – from the way we work, play, learn, socialize and travel. Numerous times, the unimaginable happened, and it is safe to say we will never see the world in the same way again. As future physicians, it is important that we recognize the challenges faced by the health care space during the pandemic, and perhaps more importantly, the everlasting transformations that our future medical students, physicians and patients will encounter. This column explores the countless obstacles we overcame and their everlasting effects, along with emerging trends that we will see in health care for the years to come.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating effects upon our nursing homes has highlighted the vulnerabilities of this sector of our health system. With increased attention to the issues in such a growing and vital part of our society, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for change.

For current third-year students across the country, the pandemic hit at a notably unstable moment in our lives. Mere months after many of us began medical school in new localities amongst new communities, all was suddenly fragmented.

There are fewer flowers in the hospital rooms now. / The ones sent to room 22 / have been taken out.

On Monday morning, a medical assistant finds me with a nasal swab in hand. I scribble my signature and temperature on the form he hands me. “Ready, Maria?” he asks, and then laughs when I groan in response. I tilt my head, close my eyes and wait for the worst part to be over. After 15 minutes of waiting in the student workroom, he tells me I am COVID-19 negative and set for the week.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdown precipitated wide-ranging effects on nearly all aspects of our society. Perhaps some of the most severely affected patients were those fighting cancer. These patients have little physiologic resistance to COVID-19 and accordingly experience higher morbidity and mortality when infected.

It is Wednesday afternoon and I have one last annual visit for the day. As I enter the room, a slender 27-year-old woman wearing a white t-shirt and baggy blue jeans sits in the chair across from me.

Students across the country in all grade levels, from preschool to graduate school, had their educational routines upended by the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdown. In medicine, there were special challenges associated with adapting safety protocols to a field that inherently requires human interaction.

Mr. T did not smile at me. No, I didn’t think it was because he was mean or anything; in fact, he was polite and had quite a calming voice. But honestly, it was hard to read someone’s facial expression behind a mask — at least during the first few months of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Many in our nation see COVID-driven requirements as anathema to their independence, but what if mandates are actually the best way to secure our personal liberties?

As COVID-19 continues to rage around the world, extended quarantine measures have been responsible for saving innumerable lives. Now, as we slowly catch glimpses of light at the end of the tunnel, or face the possibility of rising cases returning us to the heights of the pandemic, it is important to examine the long-term side effects of our self-prescribed quarantine treatment.

20 / still / except / her chest rising, falling

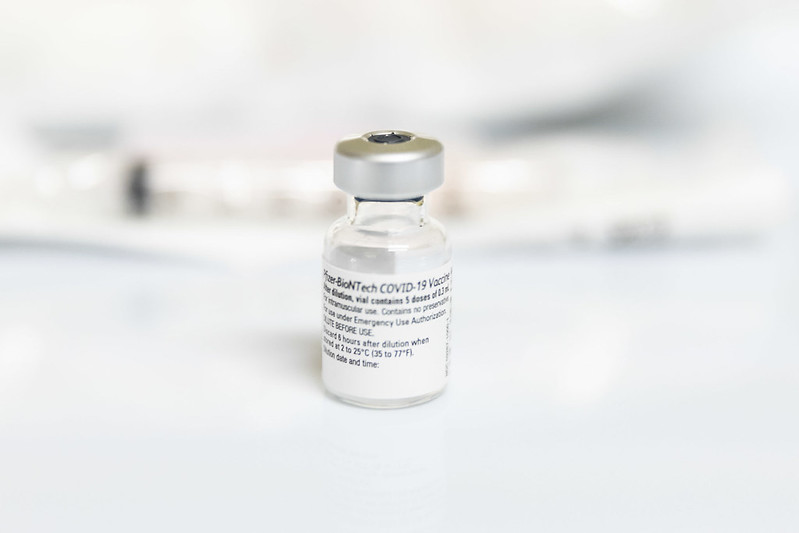

With the development and distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine and the arrival of the summer season, people are feeling happier and beginning to come out of their homes. It’s clear that there is a growing sense of hope that the pandemic may be approaching its conclusion. However, standing in the way of our pursuit of normalcy is the refusal among some to partake in the vaccine, despite its proven efficacy and safety by experts.

Haleigh Prather (1 Posts)

Haleigh Prather (1 Posts)Contributing Writer and Social Media Manager

Oregon Health & Science University

Haleigh is a third year medical student at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon class of 2023. In 2017, she graduated from Vassar College with a Bachelor of Arts in biochemistry and in 2019 she graduated from the Johns Hopkins: Bloomberg school of public health with a Masters of Health Science in biochemistry and molecular biology. She enjoys baking, painting, jigsaw puzzling and playing with her kitten in her free time. After graduating medical school, Haleigh would like to pursue a career in pediatric cardiology or pediatric surgery.