Daniel Gehlbach (2 Posts)

Daniel Gehlbach (2 Posts)Contributing Writer

University of California, Riverside School of Medicine

Daniel Gehlbach is a third-year medical student at the University of California, Riverside School of Medicine in Riverside, California, class of 2022. In 2016 he graduated from the University of California, San Diego with a Bachelor of Science in Bioengineering: Biotechnology, in 2018 he graduated from San Diego State University with a Masters of Public Health Epidemiology degree. He is committed to alleviating health disparities and bringing health equity to minorities, refugees, immigrants, migrants, non-native English speakers, the homeless, the poor, and many more. Daniel intends to practice Street Medicine in Southern California and continue to expand efforts to care for the underserved, model by example, and eventually lead and train the next generation of physicians and medical staff.

It was a Saturday morning and there were close to fifty volunteers who gathered at a homeless shelter in Riverside, CA ready to give out hygiene care packages and offer free showers, haircuts, clothes, and food. Eager medical students and physician assistants provided free health care screening and visits. Efforts like these are fairly common — nothing groundbreaking.

Rather than ask elderly poll workers to risk their health on Election Day, medical professionals and students can volunteer to work at polling locations. Health care professionals and students tend to be in a lower-risk population and are also well-versed in the public health practices critical to safely conducting an election during the pandemic.

I have learned that patients seek health care services at free clinics for a myriad of reasons and some are atypical. There were specific populations I expected to see: the uninsured, underinsured, undocumented, and those without access to transportation. Yet there were other populations I was more surprised to see, namely patients who had insurance but preferred their experiences at free clinics.

I am worried that these stories of heroism are harming the very people they celebrate. By creating an ideal “health care worker” as an endlessly altruistic individual, it stigmatizes the medical workers who refuse to take on these risks — even though there are many legitimate reasons not to.

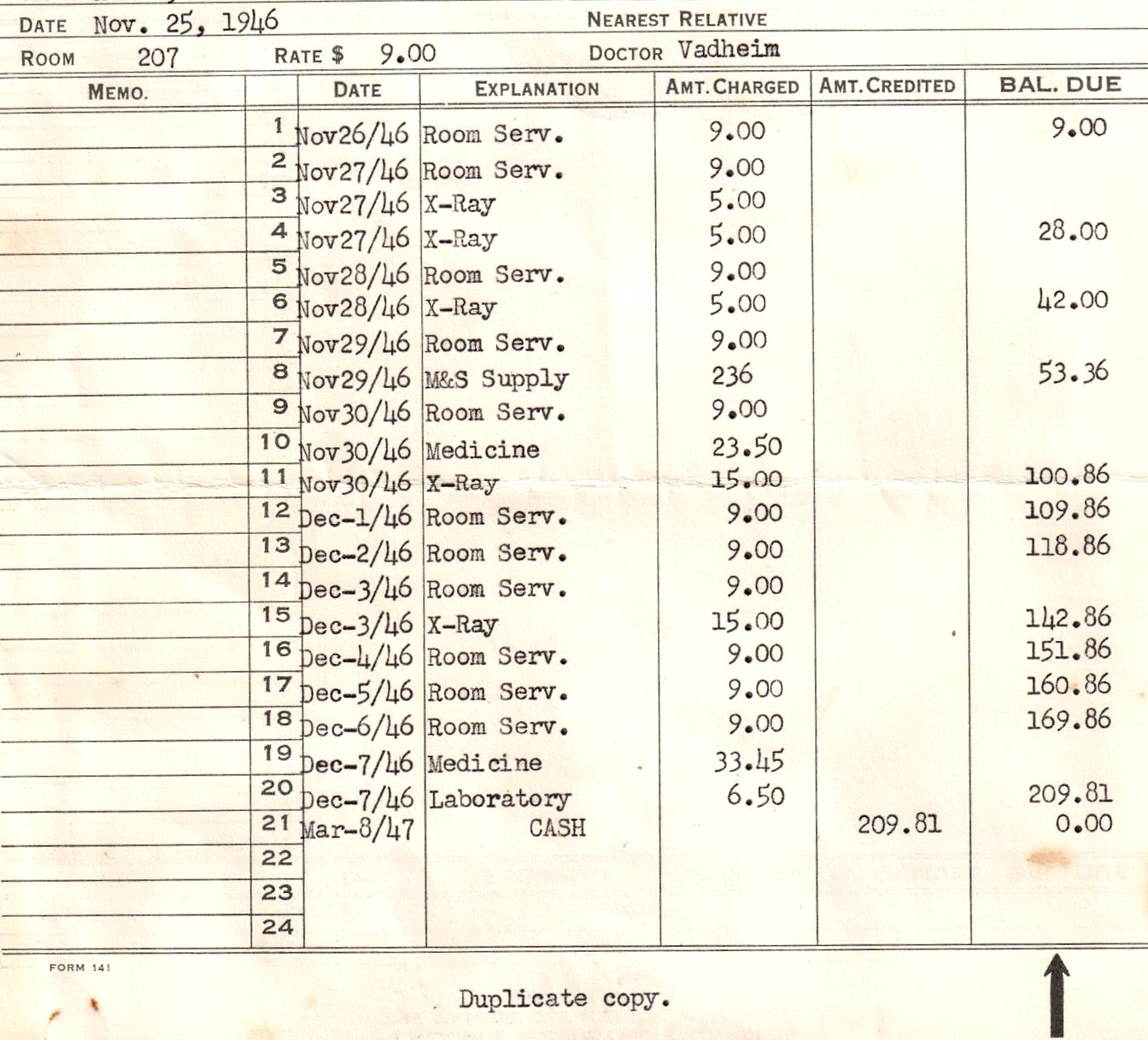

President Trump signed an executive order this past June that directs the Health and Human Services Department to develop a rule requiring hospitals to disclose online the prices that insurers and patients pay for common items and services. The rule also requires hospitals to reveal the amounts they are willing to accept in cash for an item or service. However, hospitals not complying only face a civil penalty of $300 a day, giving them latitude to effectively ignore the executive order.

As many urban academic medical centers have become the world’s leaders in research and patient care, their bordering neighborhoods have suffered through decades of disinvestment and economic blight. Medical students often receive their first years of training in hospitals that serve these disadvantaged populations. While the current focus on social determinants of health represents a rising cornerstone of medical education, what else do medical students need to know about inner city poverty?

For a variety of reasons, the substance use population is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on data from previous financial crises, the emotional toll will increase rates of new substance use, escalate current use, and trigger relapse even among those with long-term abstinence. There may be a significant lag before these changes are detected and treated because health care resources are being funneled toward the pandemic.

The incidence of chronic disease is strongly correlated with aging. According to the Information Theory of Aging, aging results from a progressive loss of genetic material due to gradually worsening cellular repair mechanisms. This cellular erosion leads to a nearly interminable list of diseases, including but certainly not limited to cancer, heart disease and neurodegenerative disease.

Mrs. H’s story is just one of millions of Americans who have become victims of structural violence and suffered from the social determinants of health. With a clearer understanding of the complex factors that contribute to patients’ health outcomes, I now aim to reunite the erroneously separated domains of medicine and social sciences.

In Nicaragua, where I was born and raised, we routinely stayed at home for dengue outbreaks, violence and hurricanes. I had experienced at least three lockdowns as a child, and now as an adult, I was experiencing another. Although the Nicaraguan lockdowns I experienced happened in the 1990s, the COVID-19 lockdown was still familiar.

As I grew up, I felt these lines and had a vague idea of where they lay. I knew where in Louisville I felt “safe,” and I also knew where the “bad parts of town” were located. The lines and their forced labels serve to enhance the lives of some people, myself included, while limiting others. Two cities exist within one border separated by an undeniable feature — skin color.

I agree that protesting is best done in peace, / But wasn’t that tried by taking a knee? / Or hashtags that said Black Lives Matter, / And praying that change would come with the chatter.

Holly Ingram (11 Posts)

Holly Ingram (11 Posts)Medical Student Editor and Contributing Writer

East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine

Holly Ingram is a fourth-year medical student at the East Carolina University Brody School of Medicine in Greenville, North Carolina. In 2016, she graduated with a Bachelor of Science in biology with minors in chemistry and anthropology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In her free time, Holly enjoys playing soccer and visiting waterfalls. After medical school, Holly would like to pursue a career in pediatrics.