I was born and raised in the east end of Louisville, Kentucky. For me, it was a normal, rather neutral city just like any other. Louisville was and still is my home. However, there is something invisible there — an invisibility born from the city’s conception. There are intangible but very real lines stretching across the districts. As I grew up, I felt these lines and had a vague idea of where they lay. I knew where in Louisville I felt “safe,” and I also knew where the “bad parts of town” were located. The lines and their forced labels serve to enhance the lives of some people, myself included, while limiting others. Two cities exist within one border separated by an undeniable feature — skin color.

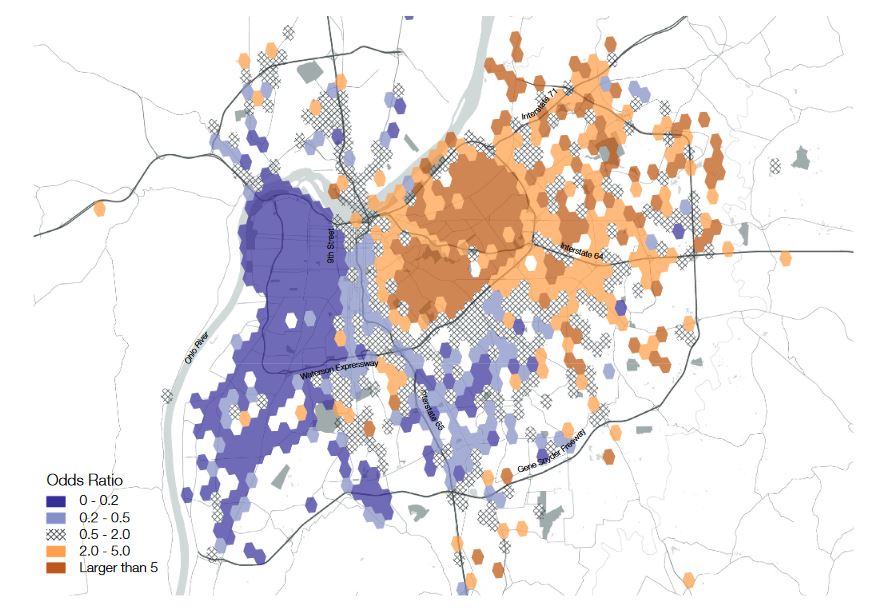

Here is an image from a study that tracked geotagged Twitter and Foursquare data to map socio-spatial relations within Louisville. In Figure 3, the purple represents the mostly Black west end and orange for the mostly White east end. The results are obvious. A distinct yet physically invisible line cuts through the city straight down the middle. The clear immobility and lack of interaction among the city’s population has a clear message: Louisville is undeniably segregated.

Louisville has an infamous reputation as one of the most racially segregated cities in the nation. Our nation’s history designed inequality from its origins through the use of slavery and white supremacy. However, Louisville continued this segregation in 1914 by the Residential Segregation Ordinance.

Next, a variation of residential apartheid grew out of the federal Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933. HOLC’s actions can be summarized as redlining — an appraisal of real estate for the purpose of focusing investments. Unsurprisingly, mortgage loans were directed mostly to White families, further intensifying the city’s lines. Nearly 40 years later, attempts were finally being made to address the city’s segregation. In 1970, Mayor Charles Farnsley declared he wanted to prevent the downtown area from becoming a “black belt.” Louisville then joined the U.S. Supreme Court initiative for school desegregation in 1975 by protecting black student’s safety on buses.

It is now 2020, and Louisville has more than a 20-year commitment to desegregating the city. The residents know the invisible lines exist, and some try to address them. But here is the truth: this commitment exists only on paper and in good-intentioned ideals. Louisville remains a largely segregated city — West Louisville is 75.7% black despite making up 23.5% of the total Louisville population. Prospect, an east-side wealthy neighborhood, is over 90% White with an annual median household income of $122,045. Compare this to Portland and Russell neighborhoods on the southwest side that have no White households with an annual median income of $8,777.

These lines do not exist officially, yet they physically cultivate stark differences on each side. Ninth street, one of the prominent invisible lines, demarcates East from West Louisville. On the eastern side, dozens of large-scale grocery stores supply fully stocked, varied products. However, on the western side, Kroger and Save-A-Lot are the only options. Nearly 50,000 people of the approximately 1.3 million people in the Louisville metro area are isolated, or more appropriately said, segregated from healthy groceries. In the absence of sufficient grocery stores, fast-food restaurants and corner stores providing unhealthy food items saturate West Louisville.

Unsurprisingly, without basic resources to live a healthy life, West Louisville residents bare the poorest health in the city. The highest rates of chronic diseases such as stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, diabetes and asthma congregate in the west and south sides of Louisville. In East Louisville, up to 10% of people are uninsured, compared to nearly 25% in West Louisville. On average, people in West Louisville have greater risks of illness and death as a result.

The recent COVID-19 crisis highlights the current state of health disparity in Louisville. The pandemic followed the city’s lines as it disproportionately hit Black residents in West Louisville. Black residents make up 23.5% of the city’s population. As of April 15, 2020, 31% of the 687 confirmed cases and 34% of the 54 fatalities were Black. Now move nearly 70 miles to the east to Kentucky’s second-largest city, Lexington, of about half a million people. Black patients make up 52% of the hospitalizations and 31% of the cases of COVID-19 as of April 8th, 2020. However, the Lexington Black population is only 15% overall. Much like Louisville, Lexington has invisible lines made apparent by race and community underdevelopment.

Do not be misled. The disproportionate patient population of COVID-19 is a direct result of under-resourced communities. Our society and the whole system was designed to continually put racial minorities, particularly Black individuals, to be most at-risk and disadvantaged in any health crisis. This disparity is often met with blatant disregard. Even prior to COVID-19, living in West Louisville compared to East reduces a person’s life span by 12 years. Twelve years is lost by crossing Louisville’s lines. A plague has already roamed the streets of Louisville and the cities of America long before COVID-19 — a plague that has been unsuccessfully hidden but willingly ignored.

On March 13, 2020, this plague put on one of its most familiar faces. Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman, was at home around midnight when three Louisville police rammed her door down. Then, the police shot her at least eight times on a no-knock search warrant at the wrong apartment. For so many other Black people throughout the nation, invisible city lines act as hotspots of police brutality. According to the website Mapping Police Violence, Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than White people. Of the killings by police from 2013-2019, 99% have resulted in no charges for the crime, including Breonna Taylor as of early June 2020. In Louisville alone, 22 people were killed by the Louisville Metro Police Department in 2013-2019. Twelve of those people (55%) were Black, despite the 23.5% Black population in the city.

The medical field must act. These numbers remain motionless. Inaction and complacency define these crimes. These factoids remain empty words subject to leisure hypotheticals and plans. While medicine exists solely to improve the lives of the people in the community, it has yet to face these realities with much success.

A 2019 study published in Science revealed a biased algorithm that guides health decisions in the U.S. health care system. According to the algorithm, Black patients are designated equally at risk as White patients despite being sicker in reality. As a result, Black patients do not receive extra care in order to preserve health costs, causing more than half of Black patients to be undertreated. In a 2015 systematic review on implicit racial and ethnic bias in health care professionals, only 1 out of 15 studies reviewed did not indicate low-to-moderate levels of bias. In other words, over 93% of the studies indicated racial bias existed in health provision. Black, Hispanic, Latino, Latina and dark-skinned people received the highest, nearly equal levels of bias.

Our medical system was designed by the same intentions that created the lines across our cities. As many deny either personal bias or systemic bias, studies reveal that racial bias exists. Not only does it exist, it permeates the entire system. Numbers reveal inequalities and function to reveal their severity. However, data and statistics are hollow and worthless without any successful action to repair a broken system. City segregation has stamped itself onto the medical system. This system has a duty to face discrimination honestly in order to provide equitable health care.

Medical students must learn to recognize the many faces of racial bias. Segregation generates increased mortality and morbidity for racial minorities and facilitates brutal police tactics. The people most at risk are forced to the front lines of the crisis. Racism is a medical issue. Bias is a medical issue. Segregation is a medical issue. The medical system has been in crisis prior to COVID-19 and remains in crisis during it. Sympathy and good intentions are polite pleasantries that crumble in the face of discrimination. While ignoring and denying these implicit biases may be self-comforting, they prop up injustice both across cities and within health care. Inaction is complicit.

Change should start from within. Medical education must use their communities and cities as case examples. By doing so, medical students can challenge a corrupt system and develop practical solutions. Volunteer with community clinics in your underserved communities. Be involved in the American Medical Association and medical activism to devise more inclusive policies. Research disparities to reveal the inequalities that need remedies. Engage your communities by talking with the people who live there. Ask them what their needs are that you might have not considered. Use your words and creativity to bring awareness to overlooked issues. Identify and correct your own biases in order to tackle systemic bias within health care. There are multitudes of ways to act, and progress needs all of us to do it. If the medical system cannot repair itself to include all patients and professionals based on race, then we are long overdue to design a system not defined by its inequity.