I went through medical school without experiencing the death of a patient I had personally cared for. In contrast to what may be seen on the trauma service, my surgery clerkship was full of routine procedures: appendectomies, cholecystectomies, port placements, excisions of pilonidal cysts and miscellaneous “ditzels,” as pathologists may refer to them as. Sure, I have had patients who were quite sick and did not have much time left to live. For example, I once performed a neurologic exam on a comatose teenager in the ICU, whose arteriovenous malformation had bled wildly out of control despite prior neurosurgery. But with the constant shuffling of rotations that medical students must endure, I was always in and out of patients’ lives before they had a chance to leave mine.

On my OB/GYN rotation, I bonded with a patient who had metastatic ovarian cancer. During her surgery, I peered helplessly over her wide-open abdominal cavity as the surgeon grabbed fistfuls of mucinous tumor and tossed them onto the Mayo tray. My heart sank when she asked me the following morning how her surgery had gone. She was a friendly woman who boldly faced her impending death. She told me that if there was a heaven, she would be looking after me. Knowing that my rotation was about to end and I would not be able to follow up with her, she asked if she could send a letter to me, once she was out of the hospital, to let me know how she was doing. Though it crossed my mind that this could be a breach of professionalism and the doctor-patient relationship, I graciously gave her my address. I never received a note.

Thus, I cannot speak from experience how I would react to a patient dying — someone who was speaking to me one day, dead the next. But I’ve learned how I may react to a patient who is already dead. I’m not talking about my anatomy lab cadaver, who was my first patient. I’m talking about a patient who was alive mere hours ago. As a newly matriculated medical student, on the eve of our first anatomy lab, I had been fearful that my cadaver would be too life-like, tricking my mind into thinking his eyes might flash open at any second. Instead, my impression was that he was so dead. I poked, prodded and dissected in relative peace, without any self-imposed hallucinations that he might suddenly wake up. Fast forward to fourth year. The hospital autopsies I have participated in all involved recently deceased, unembalmed patients — a far cry from the cadavers, who had been embalmed not once but twice, and for all I knew, were stowed in a cooler for up to a year before being unveiled to medical students. Although the cadavers played an important role in introducing me to death, autopsy pathology has pushed me further, with new challenges and greater demands for adaptation.

My first autopsy was hard enough, but I accepted it. The patient was a middle-aged woman who had a number of serious, chronic medical conditions that were thoroughly documented. Her death was not very surprising. I have also assisted in autopsies of fetuses, stillborns and neonates who died shortly after birth. Though sad, I accepted that these babies had terminal conditions, and did not have to suffer for long. They were like little hatchling sea turtles, snatched away by hungry birds before they had a chance to make it to the ocean waters. I saw it as a part of nature.

It was the autopsy of a young man, barely out of his teens, that had me doubled-over, grappling with life, death and the unfairness of it all.

He was short-statured, with thin, lanky limbs, dark hair and a farmer’s tan. As far as I know, his illness sprung on him unexpectedly, and he didn’t know he was going to die. I puzzled over his face. His expression, for the most part, was peaceful. When the endotracheal tube was eventually removed, his lips remained slightly parted, as if he had dozed off, causing his jaw to relax. His eyes, however, were shut with a subtle squint, as if he was wincing. I imagined he was still present in his body, trapped and aware … something akin to locked-in syndrome, but worse, with no ability to move his eyes. His thoughts were racing as he pleaded to know what had happened to him. And I was the only one in the room who could hear him. His struggle became more real when I went to pull his arm away from his body, so that the resident could get a better view while taking photos. Though I knew his stiff arm was simply a postmortem effect, I still imagined he was resisting us.

Goosebumps covered his arms and legs. My first instinct was that he was cold and uncomfortable, the same way I would be if I were laying naked on a metal table in an air-conditioned room. My rational side snapped back at the illusion, remembering from a recent forensics lecture that the arrector pili muscles are also subject to rigor mortis.

With the completion of the external examination, the diener stepped forward with a scalpel and swiftly sliced open his body. Of course death is final, permanent, absolute. Black and white. Yet this man’s death was becoming even more profound with each organ that was removed. After the initial Y-shaped incision, I rationalized that a person could still survive that insult. Many sutures would be required to repair the lacerations, and a good deal of narcotics would be needed. And the heart … well, there are people walking around with heart transplants. Technically they were alive for a brief time without a heart. But then came the electric saw, the chisel and the bone-cracking that signaled the removal of the skull. Snip, snip, snip … snip … SNIP! The brain was pulled clear. In my mind, there was no return. Maybe somewhere within the dead and dying neurons, chemical fragments of this kid’s memories still existed and were still residing in his body. But now even that was taken away, and stored in a bucket of formalin. I contemplated the essence of personhood. Was he still a person? Or had we turned him into the shell of a person? I thought forward to his memorial service. His family was planning on having an open casket. Who would we be fooling? Are people actually fooled, or do they just hope and beg to be fooled? My medical training has permanently changed the way I see things. I will never be able to go to an open casket funeral without picturing the hidden “pillow line” suture, running from behind one ear to the other. I’ve learned that this technique allows even a bald man to have his brain eviscerated and still keep up appearances.

At home, I searched online for our patient’s obituary. I wanted to know who he was, to acknowledge that he was a person and not just another autopsy case, as I felt the rest of the team had treated him. I convinced myself it was okay to look him up online, because it was clearly public information, out there on the world wide web for everyone and anyone to read. But there was nothing. It was too early, I figured. In the meantime, I resorted to Facebook.

I found him. At least, I was pretty sure it was him. There were only a couple of profile photos. One had dark lighting. The other was grainy, and he was wearing large sunglasses, obstructing a complete view of his face. Everything was consistent with what I knew about him, yet I wasn’t fully convinced. I was not willing to commit, as there was a chance I was mistaken. Due to the security settings of the account, there was not much else to see. I scrolled down, searching. Then I saw it, a video. Impulsively, I clicked on it. I was brought to a summertime scene in a backyard. A teenager with shaggy dark hair stepped into view. He was wearing a bathing suit and sandals. I instantly recognized him — his lanky arms, his thin, bare shoulders and his slightly stooped posture. The endearingly awkward kid I construed in my mind had now come to life. It was confirmed. Tears sprung in my eyes as I watched him proceed with the ice bucket challenge. After being doused with ice water, he laughed, grabbed a towel, and walked away. The video ended. I was glad I had left the speakers muted, so his voice and laughter did not add to the pain that was tightening its grip around my throat. As I closed my laptop and sank down onto my bed, a few more tears trickled down my face. I turned off the light and allowed myself to succumb to my fatigue.

His obituary was eventually published, and in it I found the closure I sought. Now I knew who he had been. He was a good kid. He had just finished his first year of college, and aspired to be a high school teacher. His family missed him very much. Some might argue that all this “extra information” makes these situations more difficult and painful than they need to be, but I’ve never been the type to shy away from wanting to know as much as possible. It was more important to me that I acknowledged the patient. I knew I would never meet his family, that they would never know I had been there or cared that much. Yet, I believed they would be appreciative if they knew. Sometimes, the thought alone is enough.

After this experience, I went on to complete an entire elective in autopsy pathology, but not once did I attempt to look up another obituary. Perhaps the first one was the only one I needed. It was the sense of preserving my own humanity that freed me to fully pursue the objective, investigational work that is required in the field of pathology, my chosen specialty. Perhaps in the future, as a resident and later as a practicing pathologist, there will be times where I’ll find myself searching for a patient’s obituary. Maybe that’s what I’ll need to do from time to time, in order to process, accept and move on from a particularly challenging or emotional case. I will certainly not be the only doctor to do so. Even in specialties where patient contact is abundant, physicians may still realize that they often only catch a glimpse of who their patients really are. In her New York Times article, Dr. Allison Bond eloquently reflects: “In the stream of lives and deaths we witness in the hospital, it’s easy to forget that we usually are privy to only a brief snapshot of our patients’ lives … [W]hen patients do pass away, their obituaries are a gentle reminder that behind the illness lies a story and a unique human being. That’s something that is easy to forget, but vital to remember.”

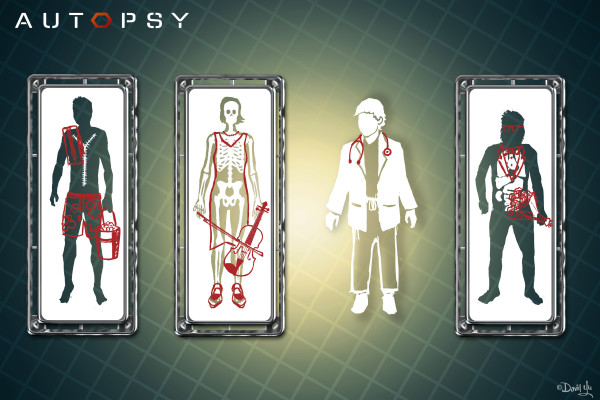

Image source: Digital illustration by in-Training graphic designer, David Yu.