Gather a group of American and Chinese first year medical students in one lecture hall, and you will notice some obvious differences right away. The Americans will likely be older with more work experience under their belt already. There will be more women on the Chinese side, and most have been full-time students all their lives. Dig beyond appearances and ask them what their daily curriculum consists of, and you will find even more interesting differences. Although they are two of the world’s largest producers of doctors and healthcare professionals overall, the Chinese medical system greatly differs from its American counterpart in both composition and organization.

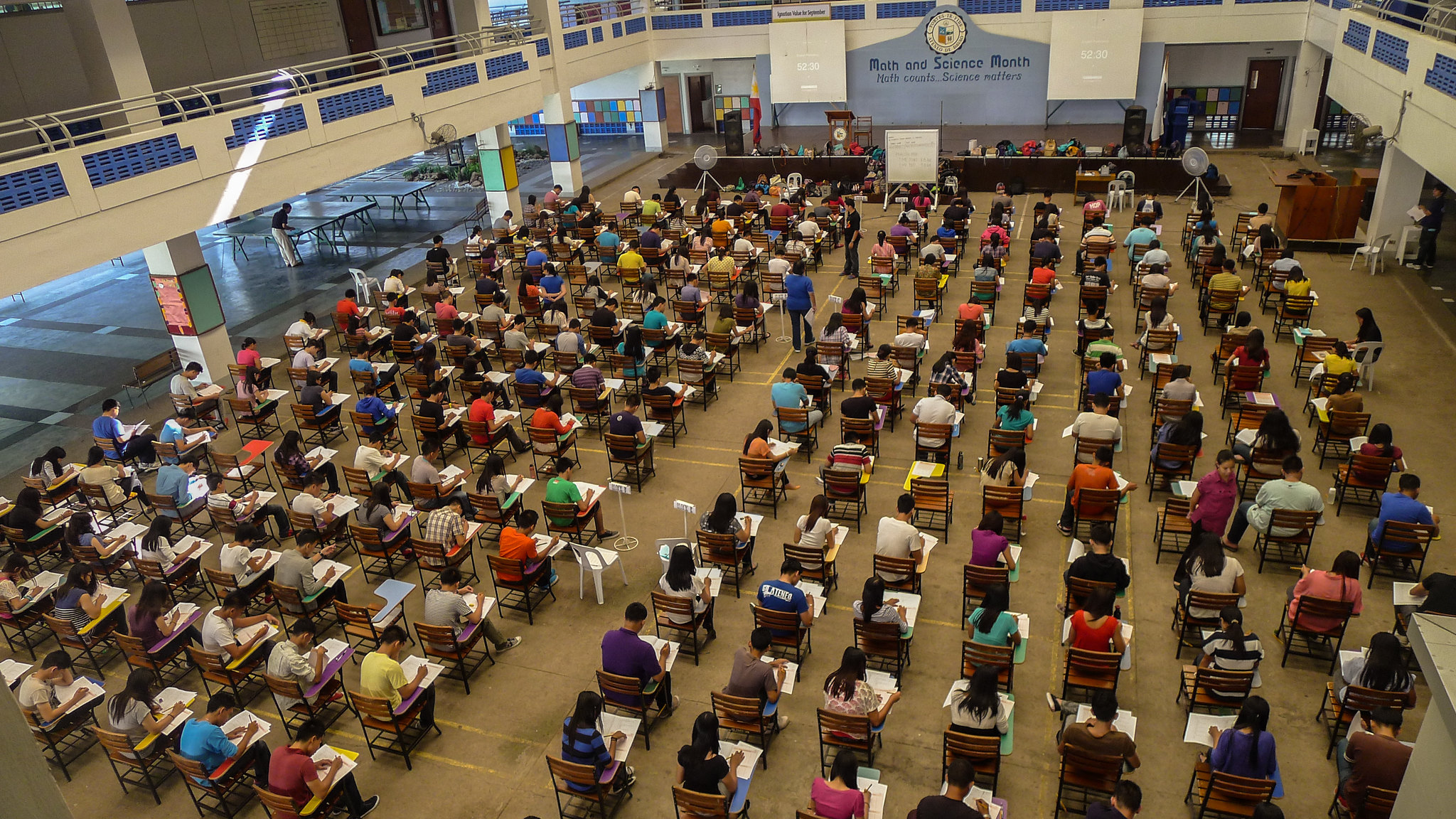

It all starts with aspiring Chinese high school seniors preparing vigorously for arguably the most important examination of their life: the “GaoKao,” or the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE). A year of ceaseless high-pressure content review culminates to a three-day, ten-hour, six-subject test. Students are given a choice to take a version of the test centered around either social sciences or natural science. Those who intend to apply to medical school must choose the latter; trying their skills in the subjects of biology, chemistry and physics in addition to Chinese literature, English and Math. After the students take the exam, they are not yet in the clear until they have completed their “College Rank Order List.”

Based on the official test solutions released in the days following the exam, the students must estimate their scores. They then compare their predicted performance against the “Minimum Score Line” published by the colleges that they intend to apply to. The next step is to rank a series of colleges in preferential order based on their predicted score — quite the gamble, since being below the minimum score of a specific college eliminates the possibility of admission entirely. If the student’s estimates are accurate and they score above the cutoff, they are entered into a matching system where the schools reciprocally rank students on their lists. The student’s admission letter then comes from the school based on this two-way matching algorithm. Those aspiring to become medical students are, like their American counterparts, typically top of their class. The key difference is that while 41% of American applicants are accepted to medical school, less than 5% of Chinese students are. The graduating class size of Chinese high schools dwarfs the number of available seats at medical schools each year. However, even those Chinese students that make the cut are admitted to programs with drastically different career outlooks.

Unlike American MD or DO schools that mostly have a uniform four-year curriculum consisting of two pre-clinical and two clinical years, Chinese medical schools each play by their own rules. There are five-year, six-year, seven-year and eight-year MD programs dispersed in medical schools throughout China. It is also important to note that Chinese medical students enter as high school graduates, typically at the ages of 18 or 19. While most American medical school applicants are required to have obtained a Bachelor’s degree, Chinese applicants are expected to finish their undergraduate studies within the medical school curriculum. Thus, it is not surprising that the five-year Chinese programs do not hand out MD degrees, but rather a Bachelor’s in Medicine (MBBS). These programs typically consist of one year of basic sciences followed by two years of pre-clinical studies, before moving onto the final two years of clinical work. In addition to Western or modern medicine, students will often be expected to gain a basic understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. Upon graduation, students will likely seek residency in small to medium-sized hospitals or community healthcare centers. Most will become general internists and family doctors, while a few become general surgeons.

A step upwards from the Bachelor’s programs are the six-year and seven-year programs, which award student degrees in Master’s of Medicine (MMed). In addition to adhering to the basic curriculum of the five-year programs, these students will be expected to take on one or two extra years in clinical practice or research work. More students gravitate towards research with some applying to short-term research positions abroad to satisfy this requirement. Upon completion, these students apply to larger hospitals for residency, mostly seeking specialization in their training. This group makes up the bulk of Chinese medical students.

The final cohort is the eight-year program: the cream of the crop who will be awarded degrees equivalent to the American MD. Only a couple dozen top Chinese medical schools offer these programs where admissions are spectacularly strict. Many of the students that end up in such programs did not take the aforementioned NCEE but have instead relied on a “Special Talents” route to guarantee their admission to these prestigious institutions. This route is not unlike certain B.S./M.D. combined programs offered in several American schools, including the Tulane Accelerated Physician’s Training Program (TAP-TP) from my alma mater. The Chinese students on this pathway typically embark on one or two more years of extra research. After graduation, most of them will fill spots in the top residency programs in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Some of them even stay with a lab to finish an additional PhD. In recent years, more and more of these students have also been trying for U.S. residencies by completing Step 1, 2 and 3 exams during their studies. Even so, due to the preferential system in the U.S. residency match for domestic medical graduates, very few can successfully earn a spot in the States.

There have been recent legislative call-to-actions in China voicing ideas to unify medical curriculums to ensure a consistent, proper level of education among different schools and programs. Such a reform would likely require Chinese medical educators to look towards the United States as a model. With the growing amounts of Chinese medical students seeking research or residency positions in the United States, this may be quite a welcoming change.

Additionally, several studies comparing the differences between American and Chinese medical students showed that empathy scores in American students were higher. This has been attributed to numerous factors, including the fact that Chinese medical students come straight out of high school and have relatively little work and life experience. Americans, on the other hand, have a more interdisciplinary education in undergraduate studies and thus exhibit more humanism in clinical practice. Critics of American medical education, on the other hand, have cited the jaw-dropping amounts of student debt associated with obtaining both an undergraduate and graduate degree. Chinese medical schools, in contrast, cost one-twentieth of their American counterparts. They are very affordable, even for the average Chinese family.

In a world where healthcare is becoming increasingly globalized, it is imperative to understand how other nations train their doctors. This understanding will serve to promote future collaboration and inspire bigger ideas that will benefit both parties. The best way forward is one of cooperation and two-way learning. Building on each other’s strengths will ultimately help both nations produce better doctors and advance the standards of healthcare worldwide.

Image credit: ACET in Ateneo de Davao University High (CC BY 2.0) by Jeff Pioquinto, SJ