Three months ago, two white men slayed Ahmaud Arbery. One of the men who committed this murder shared the gruesome video of the crime with local media, under the assumption that it would absolve him. One month after Mr. Arbery’s murder, the video went viral, being shared thousands of times as a plea to the criminal legal system: find these men and bring them to justice.

Ten nights ago, a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd while two other officers restrained him and another watched. Like the video of Mr. Arbery’s murder, this video went viral, giving millions of people unfettered access to the last minutes of Mr. Floyd’s precious life.

Importantly, this viewership does not come without offense.

Images of deeply graphic violence grants non-Black individuals a permit into the reality of police brutality against Black bodies. These ‘permits’ traumatize the Black community while simultaneously allowing the non-Black holder the right to participate as a transitory viewer. Non-Black individuals can neither begin to understand the Black experience in America nor understand the relationship between the Black body and state-sanctioned police. We can only passively view the video of Mr. Arbery’s murder: pause, rewind, replay it. We can inquire, ruminate, and speak at length but only from a place of privilege. We may watch with fury, if only for an instant.

Non-Black people can turn away. We can shift our gaze towards the unforgivable violence against George Floyd or flee from it when we are uncomfortable. These images only benefit those of us who do not experience systemic police brutality — those who are shielded from the violent arm of racism that devalues Black bodies. Our haphazard use of these photographs and videos are rooted in a long history of public ownership of the Black body, and thereby preserve the American tradition of criminalization and desensitization.

But this is not the case for the Black community. Mr. Floyd’s murder is not momentary. It is cemented in video; his pain and suffering calcified into the skeleton of our nation’s dark history, haunting Black lives daily.

It is a violation of the integrity of another human’s life to watch them die in a graphic and violent manner. After all, we rarely observe this phenomenon with non-Black bodies in our media. And in medicine, we attempt to preserve the dignity of our patients in death and dying. The recent public murders call into question the responsibility of our gaze. Why is it that the only way to mobilize non-Black individuals to observe, recognize, and act against racism is to watch a Black man die? We must do better.

For six nights, protests in downtown Portland culminated in front of the Multnomah County Justice Center, a holding cell for temporary jailing and a testament to the inextricable history of injustice inflicted upon Black America. The protests and destruction highlight the rage, despair, and hurt that flows within and throughout the Black community in Portland. In a city with such an undeniable history of racism and subsequent erasure, these events were a consequence of systemic violence and the anguish that follows.

But we should not need to view videos of Black individuals suffering or in pain in order to mobilize. Others, unrecorded and alone, die by the hands of our state. It is time for Americans to turn their gaze away from violent images of Black death and inwards to consider the invisible and not-so-invisible ways we uphold white supremacy every single day. We must recognize it in our workplaces, public spaces, and homes — and, importantly, in our clinics and hospitals.

After all, our lives as future physicians are molded by ameliorating suffering. Our patients come to us with bodies shaped by deprivation and trauma. We must understand that this pain is revealed to us in confidence, protected by the patient-physician relationship, and should be treated with grace, respect, and integrity. Just like we consume video-recorded violence, we can be transiently interested in our patient’s social circumstances and then look away when we are uncomfortable. We cannot allow this to perpetuate. We must neither passively consume their stories nor ignore them. Instead, we must hold each other accountable, recognizing that we are bound by history to uphold a moral responsibility to our Black communities.

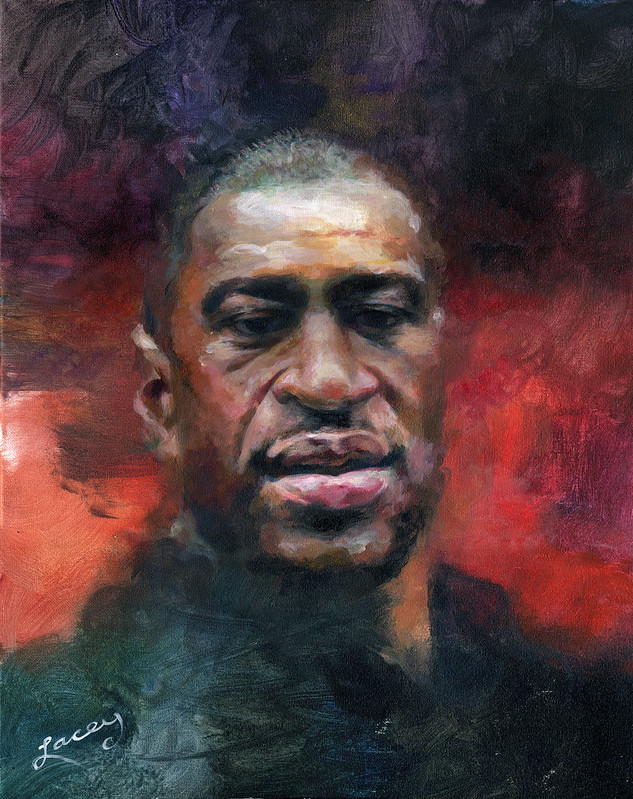

Image credit: George Floyd Portrait (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Dan Lacey