Obesity is one of the most pressing and rapidly rising public health epidemics globally, affecting 42.4% of adults and 18.5% of children and adolescents. There are many established risk factors contributing to the collective rise in body weight, ranging from individual factors such as behavior, lifestyle and genetics to societal factors such as food systems, culture, policies and safety. However, people living with obesity are heavily stigmatized in schools, workplaces, the media, public spaces and even by health care professionals.

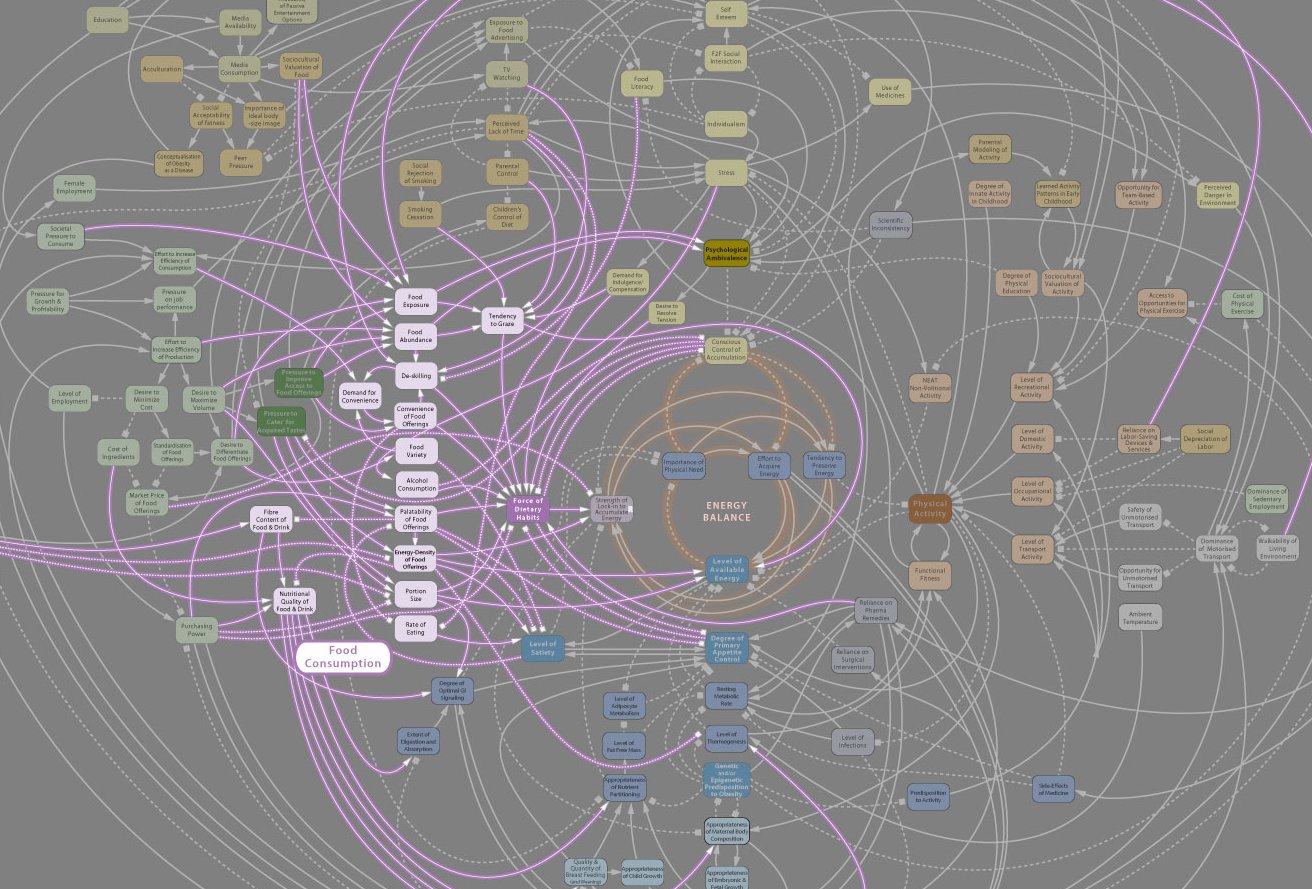

This stigma, in its many forms, has deleterious effects on patients’ health and outcomes, including associated comorbidities and further increases in weight gain. Our understanding of obesity in Western medicine boils down to a basic model of energy expenditure: if we eat too much or exercise too little, we gain weight. While we know about the multitude of external factors that contribute to this formula, the focus remains on the individual’s decisions. Given the complexity of personal, cultural, economic, and social risk factors precluding a public health “cure” for obesity, we must wonder about the limitations of our medical knowledge. Perhaps, it is an issue of how we see and understand obesity itself — an individual’s burden from a systemic issue?

Those who live with obesity are expected to undergo Herculean efforts to somehow fight against systemic, external and internal forces in the quest to achieve a BMI below 25. Unfortunately, they are considered a failure by society, doctors and often themselves if they are unable to successfully fight the factors contributing to their health. This only worsens the stigma, causing poor outcomes and inadequate care for those dealing with a multifaceted condition.

As a physician-in-training, I have seen this dynamic play out in the office setting numerous times in the form of palpable discomfort on both sides. Physicians tend to see patients living with obesity as non-compliant, sometimes faltering when deciding whether to bring up the “diet and exercise talk” at each encounter (regardless of the reason for their visit). It is incredibly demoralizing to be told to lose weight when you have an ear infection. On the other hand, physicians commonly lack training in initiating constructive conversations about weight, in turn avoiding the subject completely. As a result of these varied clinical encounters, patients may also feel uncomfortable discussing their health fears and struggles with their physicians. I personally understand that feeling because I was once that patient, nervously awaiting the painful conversation about the weight I could not seem to lose.

At the age of 22, despite an intensive keto diet, gym regimen and use of diabetic weight loss medications, my body just would not shed weight. I was offered bariatric surgery as a last-resort option. Despite its potential efficacy, I balked. I felt too young to undergo such an invasive surgical procedure to alter my organs, yet I yearned for a way to work with my body. I grew up steeped in the shame of living with obesity as a child, adolescent, teenager and young adult; this was worsened by comments by family and friends who felt that their advice to “just lose weight” would be encouraging. I found myself at the intersection of cultures, diets, exercise plans, doctors, bullying and distress.

Even as I achieved academically, I was constantly confronted with the notion that I would never be truly heard, only seen and judged. I accumulated diagnoses of mental and physical illnesses including obesity, fatty liver, gallbladder stasis, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, polycystic ovarian syndrome with hirsutism, pre- diabetes, pre-hypertension, depression, anxiety and insomnia, as well as the side effects of their respective prescriptions. I felt an ever-growing sense of helplessness: a wound worn daily on my body, prodded and poked by every painful doctor’s visit. My physicians were unsure of how to guide me, perplexed by the mismatch of biological equations with my reality. Now as a medical student, I sit on the other side of the clinical dyad, observing how the medicine of obesity is taught and fails to equip budding physicians with sufficient tools to address the systemic factors impacting weight loss. I believe we must re-imagine a new holistic model of care.

To better examine our current approach, an exploration of how obesity and its treatments are understood by other systems of medical science may be helpful. For example, traditional Chinese medicine, originating as early as the Han dynasty (202-220 BCE), has reports of multi-modal obesity treatment regimens consisting of herbal medicine, acupuncture, lifestyle counseling, massage, qi-gong (martial arts) and more. However, the fundamental focus of treatment is not on weight loss, but on internal re-balancing to regulate food intake and body fat content. While treatment success still depends on individual lifestyle modifications, it becomes one of several modalities necessary to achieve holistic restoration. This framing may be beneficial to patients’ sense of confidence and help renew their partnership with their physician.

Similarly, traditional Indian medicine or ayurveda, views excess body weight or obesity as a metabolic disorder stemming from intrinsic, lifestyle, environmental and even seasonal factors that lead to an elemental imbalance in the mind and body. This imbalance leads to excess accumulation of adipose tissue, toxins in the digestive tract, mental sluggishness/depression, poor digestion and slow metabolism that perpetuates the cycle. A simple direction to eat less and exercise more, or even a surgical intervention, would be inadequate in addressing such complex mind-body interactions. Rather, the Ayurvedic approach is meant to teach the individual about the effects of their lifestyle, routine and environment on their mind and body, relative to their individual natural body compositions.

I was fortunate to receive Ayurvedic treatment and spiritual guidance while addressing my battle with obesity, learning how to maintain balance through my lifestyle. As I focused more on the effects of my activities, the properties of my food and even my thoughts on my inner balance, I was able to stop counting calories and tracking macronutrients. I was more driven and less stressed than ever while striving to achieve better health. Ironically, as I finally shifted my focus away from judging my body, I found my self-esteem in my ability to nurture myself. At this point, the pounds began to fall steadily and consistently. Ayurveda helped me to find the radical self-love and self-efficacy that I needed to improve my health. I lost seventy pounds and gradually discontinued all of my medications. Instead of breaking myself down into a thinner body frame, I was taught how to build myself up.

As physicians, we must work to lift patients up when they are struggling, rather than shaming them into well-being. As Dr. Donald Berwick once noted, it is not always patients’ diagnoses, but their helplessness that kills them. Indeed, the helplessness we instill through our focus on individualism and molecular pathology in the clinical setting will ensure that this epidemic kills millions prematurely and costs billions of dollars. If obesity is a disease caused by society — its inequities, trauma, and expectations — then the solution for obesity should address more than just the patient sitting in front of us.

Traditional medicine approaches are not routinely utilized in Western medicine, but it is critical that we consider expanding our outlook to address obesity. There is much to be learned from these models of holistic care to improve patient well-being. Health care professionals can appreciate that there are ecological factors beyond individuals’ control driving significant physical, emotional, mental and spiritual stress. Physicians should be aware of the limits of looking through a single lens to address such factors and can seek inspiration from traditional medicine to widen their view and help patients balance their external context and internal reality. This will result in the ability to make sustainable, healthy changes. We must address what our patients have been through and the influences carving out their path ahead to effectively accompany them along their journeys towards well-being.

Author’s note: This article is a part of work of the Aseemkala Initiative (www.aseemkala.org), an organization aimed at transforming medicine through diverse cultural knowledge. Shradha is a Aseemkala Research Fellow.

Image credit: Obesity System Influence Diagram (CC BY 2.0) by pushandplay